Grated carrots do little but add a dry, tasteless crunch at U.S. salad bars, but in France they stand alone, becoming a salad unto themselves.

Considered an iconic side dish, salade de carottes râpées shows up on most any bistro menu. It’s part of a family of grated salads that are a rare instance of raw vegetables in classic French cooking.

And it’s such a simple thing. Grated carrots, a bit of oil, a touch of sugar, some lemon juice or other acid, perhaps some fresh herbs. Satisfying, clean flavors abound. Why does it work?

The transformation begins with the grating, a preparation we rarely use in the U.S. And we discovered it serves a dual purpose, changing both taste and texture in ways no amount of slicing or dicing can replicate.

We thought we were just imagining that grated carrots taste sweeter and fresher than chopped or sliced, but they really do. When a carrot (or any root vegetable, for that matter) is cut, its cells rupture and release sugars and volatile hydrocarbons, the sources of the carrot’s sweetness and aroma. The more cells you rupture, the sweeter the carrot will taste. And grating ruptures more cells than almost any other prep technique.

But it also changes how the carrots interact with the dressing. Grating creates a more porous surface on the resulting shreds of carrot. It also exposes more surface area. The combination means more dressing comes into contact with more carrot. The result is that a minimal and simple dressing has an outsized effect on the finished dish.

As we tested, we quickly learned that fresh carrots are essential. Many bagged carrots are dry and woody. Grocers usually also sell loose carrots, sometimes with the greens still attached. We found these to be freshest.

For grating, the French have long favored handheld rotary graters (we think of them as cheese graters), but they are rare in American kitchens. We favored a food processor fitted with the grating disk. Not only was it fast and easy, it also produced meatier shreds than a box grater.

It’s not your imagination. Grated carrots really do taste sweeter than whole, chopped, sliced or diced. In fact, you can get the same effect with just about any root vegetable. Why?

The cells of vegetables such as carrots, beets and parsnips contain heaps of sugars and volatile hydrocarbons, the sources of the vegetables’ sweetness and aroma.

When those cells are ruptured, those sugars and hydrocarbons are released, changing the way we taste the vegetable. The more cells are ruptured, the sweeter the taste.

Slicing, dicing and chopping certainly rupture cells but not nearly as thoroughly as grating

Fresh herbs were a must. Tarragon, thyme and parsley are traditional. We liked the combination of tarragon and parsley best, but thyme and parsley were great, too. As for the parsley, the more the better. Most recipes add a tablespoon or two, but we found that a full cup of chopped parsley lightened both the flavor and texture of the carrots.

The earthy sweetness of the carrots needed to be balanced with a bit of acid. The classic choices—red and white wine vinegars or lemon juice—were too sharp and assertive. The winner for our French salad ended up being from Italy—white balsamic vinegar.

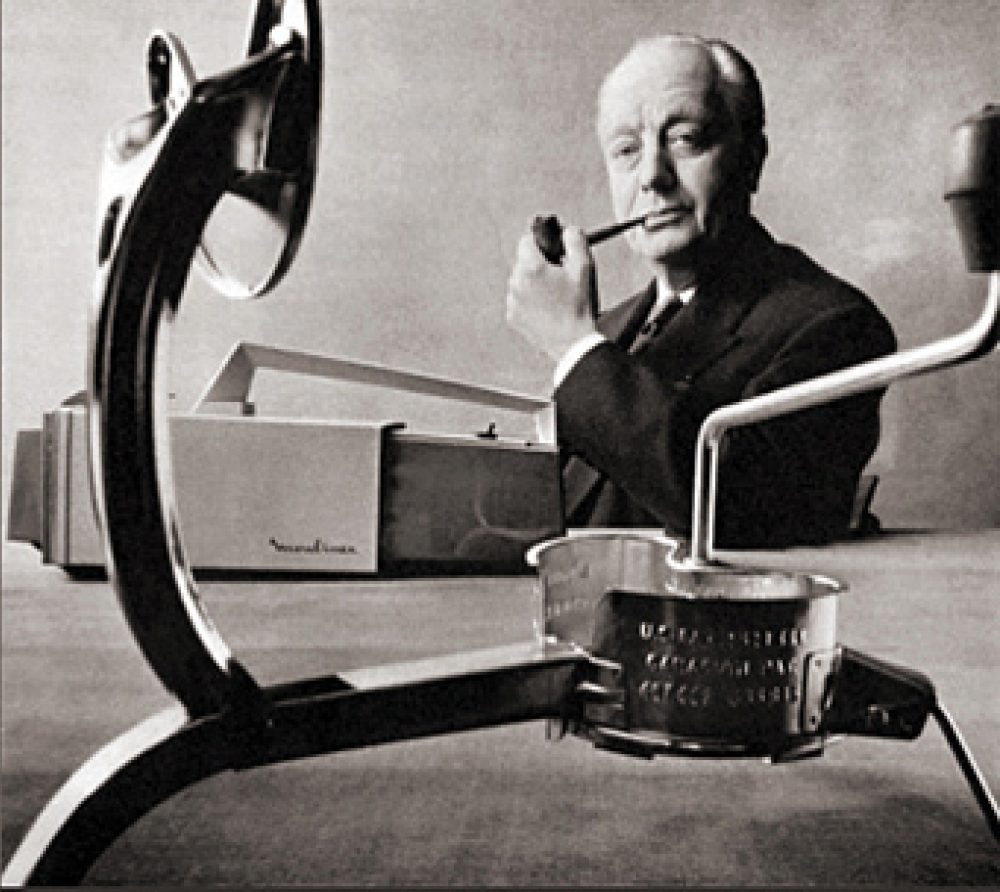

Frenchman Jean Mantelet owes his kitchen appliance empire to lumpy potatoes. It began when his wife was unhappy with a German potato masher he’d bought for her. So he set out to do better. A gadget maker by trade, he created a newfangled presse-puree, or mechanical food grinder, and soon was selling it at open-air markets.

That was in 1932. Over the next decade or so, he would invent a variety of grating and grinding tools, but he became best known for a hand-held drum-style rotary grater. Advertised with the promise to grate food “right down to the last crumb without skinning your knuckles,” the devices made it to the U.S. by 1949, where they sold for $1.

Mantelet called his company Moulin-Légumes (vegetable mill), but customers shortened that to Mouli (which also became the nickname for the rotary grater itself and—confusingly—several of his other products). Today, we know the company he founded as Moulinex. By the 1970s, it was estimated that the typical French household owned four of his gadgets.

French housewives didn’t rush to embrace the Mouli until Mantelet slashed prices. Then things took off. That’s when they discovered the ease with which it produces classic French salads—such as julienned beets or celery root remoulade—minus the finicky knife work. Press accounts from the time praised the device for its ability to grate everything from cheese, nutmeg and root vegetables to coconut, chocolate and nuts. And on the beverage side, it could pulverize ice finely enough for a crème de menthe frappé.

Mantelet prided himself as liberating women from kitchen drudgery (albeit not from the kitchen itself). “I always wanted to sell something women could use. In fact, from a business point of view, I have always been a ladies man,” he told The New York Times in 1977

White balsamic is a low-acid, semi-sweet vinegar produced without the slow caramelization and oak-barrel aging of traditional balsamic vinegar. Its neutral profile pairs well with many flavors and beautifully balances dressings and vinaigrettes. In our salad, it provided the kick the dressing needed without calling attention to itself. And that allowed us to up the ratio of vinegar to oil (1:2) to get a punchy flavor without overwhelming. It also pairs particularly well with a bit of honey, which we preferred to sugar to heighten the natural sweetness of the carrots.

Getting the dressing-to-carrot ratio right was essential. Too much dressing made for a soggy, slaw-like salad. Too little and we had a heap of dry carrots. Thanks to the grating—as well as moisture added by the fresh herbs—we found we didn’t need nearly as much as we expected.