We’ve always been a bit shy when we shake our cocktails, convinced the longer we rattle our liquor around with the ice, the more diluted and less delicious our drinks become.

But in Peru, we noticed bartenders aggressively shaking the country’s signature drink—the pisco sour, a frothy blend of brandy, syrup, citrus and egg white. Sometimes they shook for 30 seconds or more, with splendid results. The foam was rich and stable, the drink perfectly chilled, the flavors balanced.

It turns out we’ve been going about shaking all wrong, and we’re not alone.

We turned to “The Bar Book” author Jeffrey Morgenthaler to teach us about the science of shaking. He confirmed most of us generally stop shaking way too soon.

“A lot of people worry that if you shake too hard or too long, it gets watered down,” Morgenthaler says. “But ice regulates itself. Once the drink gets cold enough, ice doesn’t really melt anymore.”

Because of the way heat transfers from alcohol to ice, cocktails cool more slowly than plain water—meaning the ice in your booze melts more slowly than in a glass of water.

How cold will your drink get? Depends on your freezer. Once water freezes at 32°F, it doesn’t stay at that temperature. Ice is as cold as the freezer it’s stored in. So for colder drinks, turn your freezer down.

Size matters, too. Small ice cubes cool drinks faster and melt more quickly. Use small cubes for shaking a cocktail and larger cubes (which dilute drinks more slowly) for anything on the rocks. Cocktails actually benefit from a bit of dilution. Slightly reducing the proof of a liquor allows us to better taste its flavors (rather than just the alcohol).

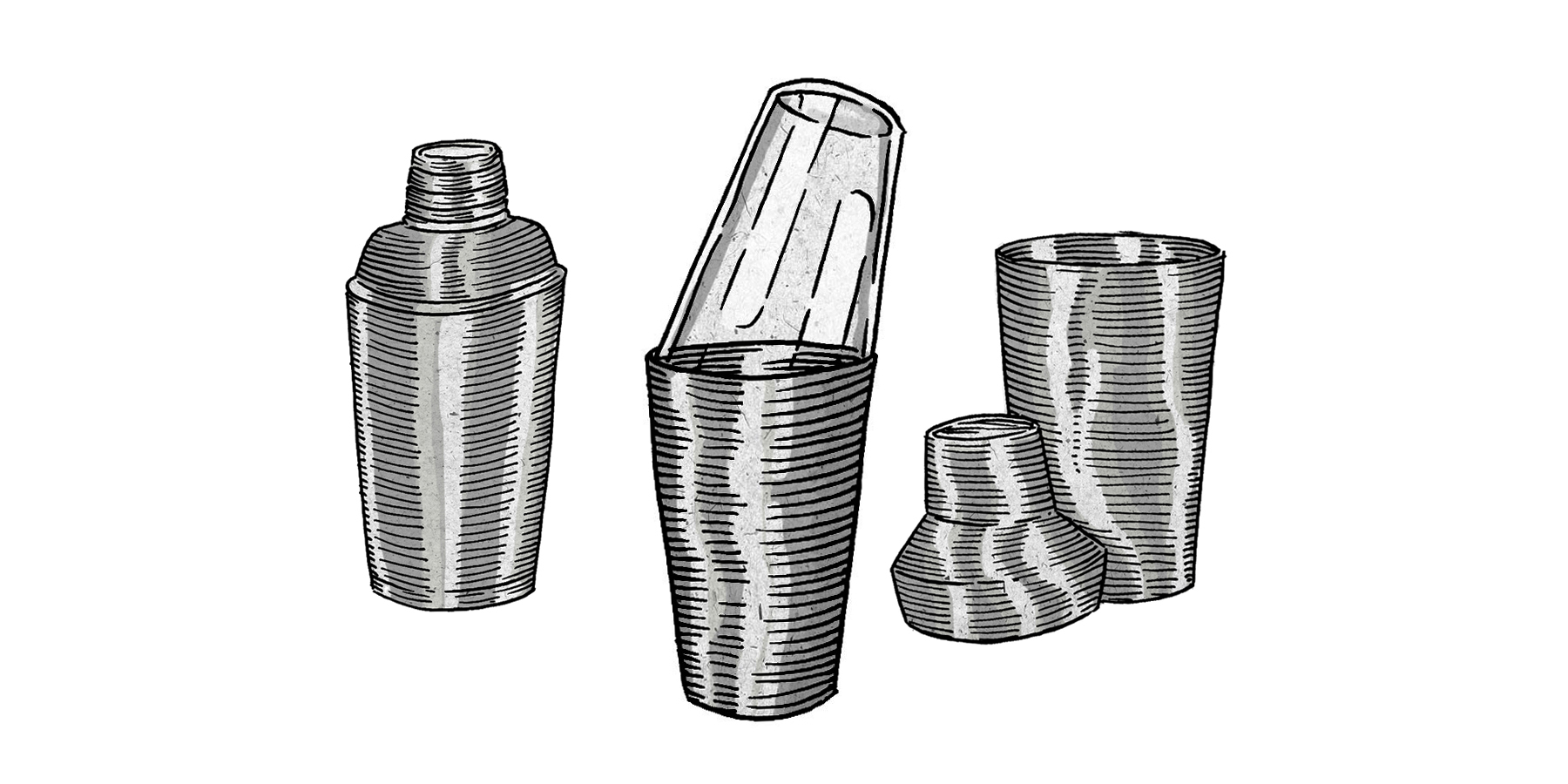

When it comes to purchasing a cocktail shaker, there are three styles to consider: the cobbler, the Boston and the Parisian.

Nearly all are made of metal, which chills and contracts when loaded with ice, creating a vacuum seal. Breaking that seal to pour the drink can be difficult. “It’s hard to tell people they need to go buy a $100 shaker, but it’s also hard to tell people there’s some sort of magic trick to getting a $6 shaker apart,” says Jeffrey Morgenthaler, author of “The Bar Book.”

Most people shaking cocktails at home use the cobbler, which has three parts: a cup, a lid and a cap that includes a built-in strainer. Trouble is, most of them are made of thin metal that’s prone to freezing shut. If you opt for this style, look for one with thick walls, such as those made from heavy-gauge steel.

Morgenthaler prefers the two-piece Boston shaker, which consists of two cups, one smaller and one larger. To shake, the smaller cup—which can be made from steel or glass—is inverted into the larger. Thickness is less important in this design. Focus instead on how deeply the smaller cup fits into the larger. A deeper fit makes a better seal and is easier to open. A small mesh strainer or cocktail strainer is used to pour the drink.

The third type of shaker—the Parisian—is less common. It resembles a cobbler shaker in shape but functions more like a Boston shaker in that it has two cups and no strainer.

Whichever style you pick, proper shaking is a two- handed operation. Grasp the bottom of the shaker with one hand and the top with the other. Hold the shaker parallel to the floor and shake it back and forth, not up and down—which doesn’t circulate the ingredients as thoroughly. Larger, colder ice should be shaken for a longer time than smaller, wetter ice, but Morgenthaler recommends an overall range of 15 to 20 seconds.

Not up to shaking? Morgenthaler offers a fourth option: a blender. “That’s a really great trick for using the smallest amount of ice and having a nicely shaken drink,” he said. “Just a large cube in the blender, and run it until it’s silent.”

Shaking aerates cocktails, creating tiny bubbles that are key to a frothy cocktail. Froth is simply a light foam, or gas bubbles dispersed in a liquid. In substantial foams like whipped egg whites or the foamed milk on top of a latte, the bubbles are stabilized by protein.

In a cocktail—which rarely has protein—froth is often stabilized by syrup. As ice moves through the liquid, it creates trails of air. Those trails collapse into air bubbles, creating froth. The syrup creates a viscous film that surrounds those bubbles, strengthening them.

All of which means the more ice you use and the longer you shake, the more air bubbles you get. The thicker your syrup, the more stable those bubbles will be. At Milk Street, we find syrups made with a 2:1 sugar-to-water ratio work better than the more common 1:1.

When to shake? Let the ingredients guide you. Certain ingredients—fresh juices, egg whites and cream—call for shaking. “Anything opaque,” Morgenthaler suggests.

Ice should be the last ingredient added to the shaker. Don’t skimp.

“Get as much ice as you think you need, and maybe triple it.”

Our shaken cocktail recipes make two drinks each but can easily be halved (you’ll still use one egg white for the pisco sour). If you don’t have a cocktail shaker, use a lidded jar large enough to accommodate about 6 ounces of liquid plus 2 cups of ice. To make simple syrup, combine two parts white sugar and one part water in a saucepan and bring to a simmer to dissolve; cool before using. Extra syrup can be stored for a month.