The Potlikker Papers: A Food History of the Modern South

By John T. Edge

The first half of John T. Edge's The Potlikker Papers is about the fight for civil rights and how cooking played a central role. Cooks, such as Georgia Gilmore, ran private restaurants in their homes, creating an underground economy that not only supported African Americans during the Montgomery bus boycott, but also brought together the likes of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., Bobby Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson. Edge also introduces us to Booker Wright, a waiter at Lusco’s in Greenwood, Mississippi, whose brilliant turn in a 1966 NBC News special was a clarion call for better race relations. (Booker’s famous line: “The meaner the man, the bigger the smile.”) Along the way, Edge provides a few other fascinating culinary tidbits: The fried chicken chain Popeyes Louisiana Kitchen was named after the main character in “The French Connection,” not the cartoon; confederate widows wrote charity cookbooks to pay for artificial limbs and crutches for Civil War survivors; and that steaks at Johnny Reb’s Dixieland could be ordered Shermanized (burnt to a crisp), Lincolnized (warm, red heart) or Stonewalled (rare). The transition from the heartfelt history of the civil rights movement to modern day Southern cooks—including Craig Claiborne, Bill Neal and Nathalie Dupree—is a two-course non sequitur, but if you think you know something about the grit, character and wit of the everyday Southerners who powered the civil rights movement, The Potlikker Papers will convince you otherwise

Yeah, I know the problem. Cookbooks about the philosophy of cooking are hard to follow and harder still to use. Just give me good recipes and I’ll do the rest! But the culinary world is at a watershed moment, the precise instant when home cooks are interested in why certain ingredients make good bedfellows. The Art of Flavor advances that cause with a refreshing twist by pairing a perfumer (Aftel) with a bay area chef (Patterson). When Patterson builds a dish starting with carrots, he asks whether one is looking for a mélange of flavors or contrast? Are the carrots freshly picked with bright flavors, or a bit limp, having been dragged out of cold storage? Which citrus flavors marry best? Each has its own effect from lime to lemon to orange. And what about contrast? Cumin does the trick. And if one wants to create a whole new flavor? Roast the carrots on a bed of coffee beans. Then we get into rules: Similar flavors need a contrasting flavor; contrasting ingredients need a unifying flavor; heavy flavors need a lifting note; and light flavors need to be grounded. This is not a quick and easy read but Patterson and Aftel, like any good teachers, take it one step at a time and provide recipes as examples. This is a multi-course tasting menu that leaves one intrigued but satisfied.

The Art of Flavor: Practices and Principles for Creating Delicious Food

By Daniel Patterson and Mandy Aftel

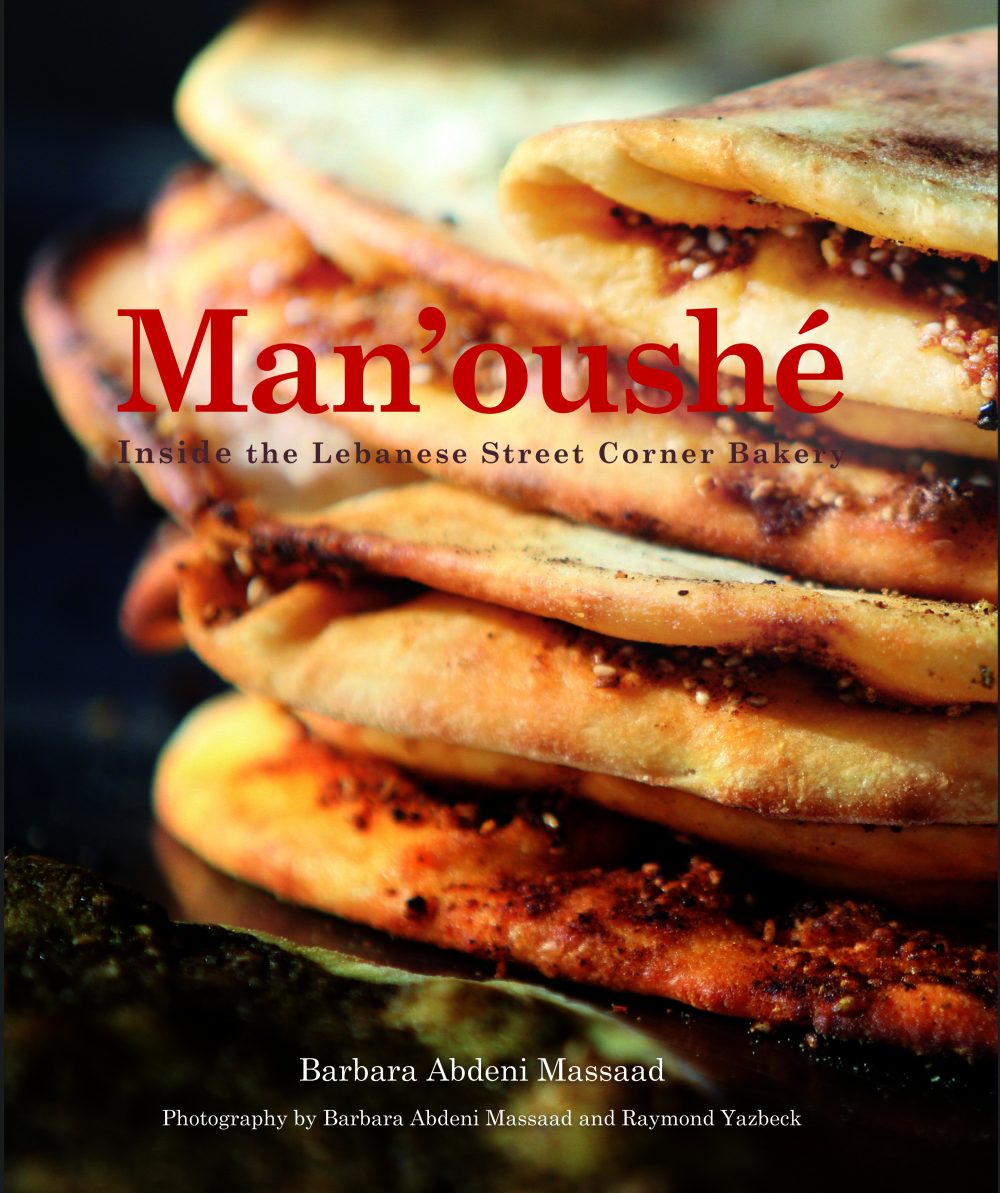

Man'oushé: Inside the Lebanese Street Corner Bakery

By Barbara Abdeni Massaad

Other than pizza, flatbreads have played almost no role in the history of American cooking. But they are headed to the front of the bread line with a vengeance since they offer infinite variety and are quick cooking. Let’s start with the basics. The name of the book, Man'oushé, refers to the classic Lebanese breakfast—a flatbread topped with thyme, sumac, sesame seeds, salt and oil (though dozens of other toppings are possible, including cheese, strained yogurt, preserved meat, vegetables and kishk, a powdered mix of bulghur and yogurt. This is a yeast bread, though many flatbreads from around the world can be made with baking powder. Massaad also includes two other dough recipes, one for Arabic bread (pita) and one for paper-thin bread, which is traditionally cooked on a “saj,” a convex metal disc (a cast-iron griddle also works). Massaad also includes recipes for turnovers and plenty of variations. This is a not a comprehensive book on flatbreads; Man'oushé is about Lebanon. But for me, it’s a new world of breads that have taken over my imagination and kitchen.

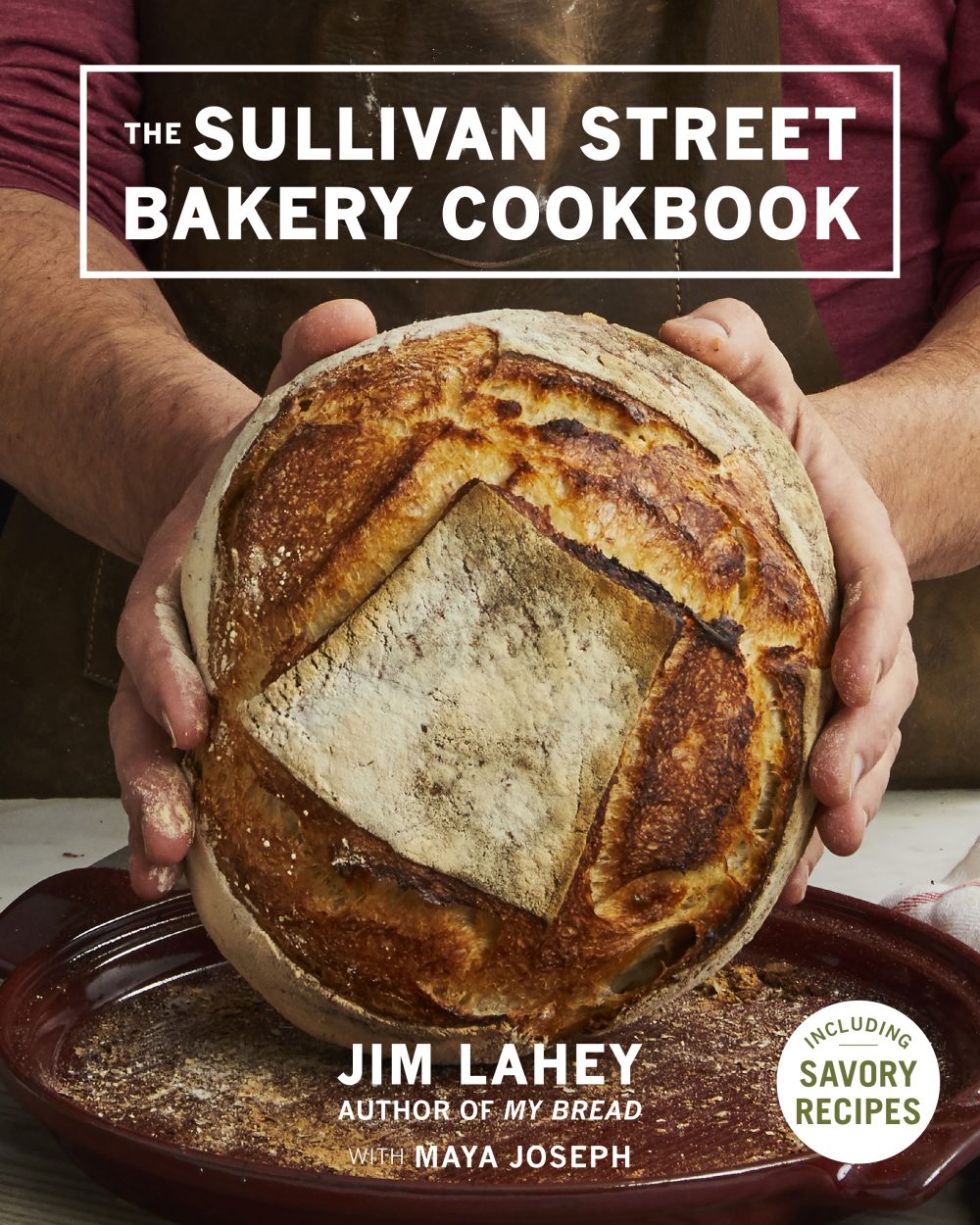

Jim Lahey is most famous for his revolutionary recipe for no-knead bread—a very wet yeast dough that is baked in a Dutch oven in which the resulting steam produces a crackly professional crust. He continues the tradition of very wet doughs that require no kneading with a twist: most of the recipes in Sullivan Street use a homemade starter and biga—starter, flour, water and salt—that is used as a pre-fermented base for the recipes in this book. (A handful of the recipes are made with commercial yeast; a few with baking powder or soda.) Instead of kneading, one requires time and a bit of folding and so Fahey’s recipes are, for the most part, all-day affairs. (Water and flour produce gluten given time.) However, there is little skill involved and almost anyone can turn out spectacular breads, bombolini (doughnuts), bread puddings and cakes. Lahey also provides recipes for pizzas, sandwiches and the like that put these recipes to good use. This is not the science of bread. “Modernist Bread, a laboratory tome on the science and art of bread baking. It’s a charming, personal approach to bread from a grand master.

The Sullivan Street Bakery Cookbook

By Jim Lahey with Maya Joseph