Onions play a central role in chicken yassa, Senegal’s tangy-sweet braised chicken, so we tested our recipe using four of the most common varieties: yellow, white, red and Vidalia. To further evaluate their differences, we also compared their flavors when raw and simply sautéed in oil and salt.

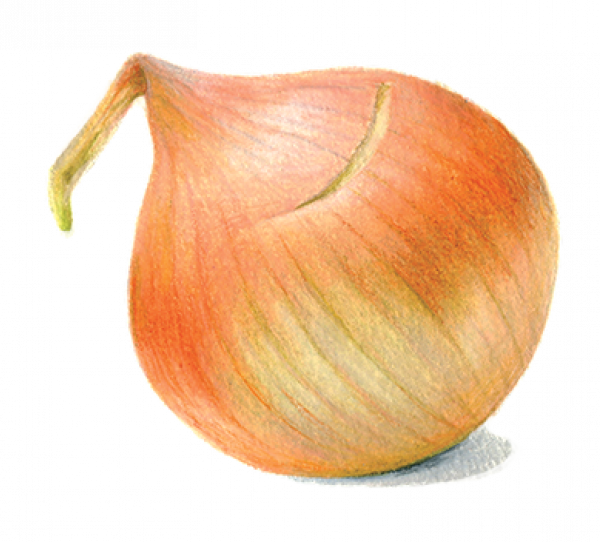

Yellow: Also known as Spanish or brown onions, these are what we use most at Milk Street. Pungent when raw and slightly sweet when cooked, yellow onions are perfect for chicken yassa, readily taking on lime juice’s sourness but balancing it with their sweetness. If a recipe doesn’t specify onion type, use this.

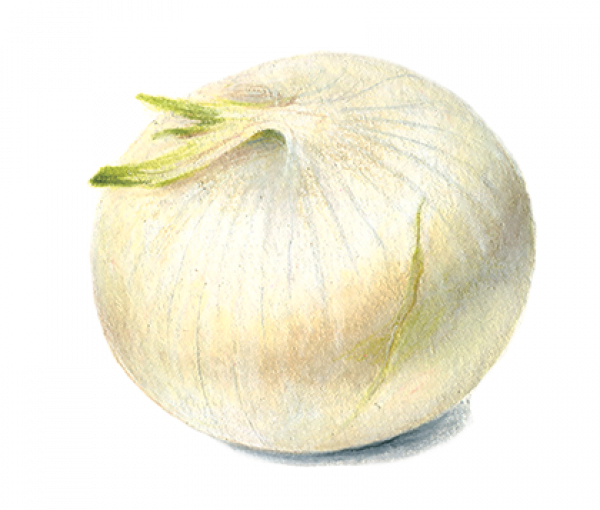

White: Milder than yellow when eaten raw, in our testing, white onions lost much of their flavor when cooked. Their watery texture felt out of place in our braised chicken. Instead, we like them best raw, adding crunch and slight pungency to guacamole, salsas, tacos and deli sandwiches.

Red: Red onions maintained a pronounced astringency in both raw and cooked tests. Though they developed some sweetness in the braised chicken, their pungency seemed out of place and their color muddied the dish. We like using thinly sliced red onion in salads, for pickling and anywhere some color and oniony bite is desired. It can also provide texture and brightness to stir-fries.

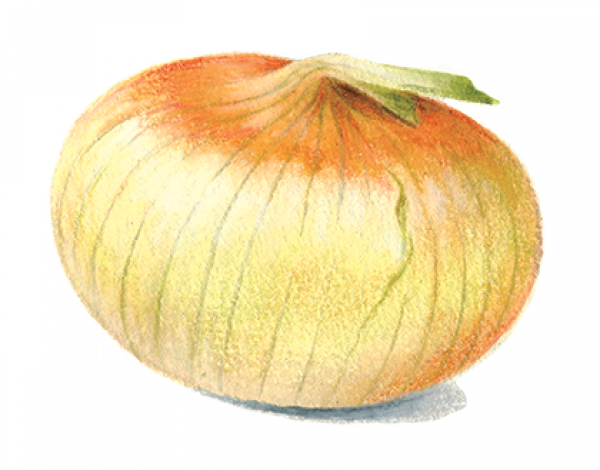

Vidalia: These squat, seasonal Georgian onions have a reputation for being some of the mildest in the onion family. In our testing, they were the least astringent variety when raw and, when sautéed, their sweetness was even more pronounced, masking other flavors in our chicken yassa. When we want sweet, oniony flavor—in a caramelized onion jam, or as a raw topping for burgers—we use Vidalias. If they’re out of season, look for other sweet onions (Maui, Walla Walla) as a substitute.

We were going for a special kind of barbecue, Pierre Thiam told me. For me, that conjured up notions of a neighborhood street scene: a crowd, smoke, local beer and the opportunity to mix and mingle with friends and strangers.

But the actual destination that the Dakar native, New York chef and my culinary guide in Senegal led us to was in the ground floor of a downtown building in a cavernous, poorly lit series of alcoves. Each contained a large square brazier built into a low table, attended by a cook and surrounded by benches.

Beef, chicken and assorted hearts—threaded onto wooden skewers, served on green-lined paper with mustards, ginger, spices and cooked onion—were the specialties. My neighbors to either side, businessmen and blue-collar workers alike, were friendly. Yet there was a slight sour note as well: The owner of the establishment was clearly unhappy about our camera crew and, since I do not speak Senegal’s most widely used language, Wolof, I could only guess at the reasons. Finally, after standing behind me and staring angrily into the camera, he prompted a sit-down at which matters were resolved and we parted good friends. It was a taste of sweet and sour.

That night, after a long, hot day of filming, we retreated to the open-air hotel porch for a cool cocktail and dinner. I ordered the chicken yassa, one of the dishes on my “must-try” list. Yassa is a simple recipe of marinated chicken braised in a sea of cooked onions flavored with lime and, at least in Senegal, Scotch bonnet peppers. One thinks that the onions are going to be too sour, but they’re not. A portion of the onions simply melts into a sauce, creating an unexpected harmony of sweet and sour that coats the juicy seared chicken.

At Milk Street, adapting chicken yassa was simple enough. We built the marinade on a base of peanut oil and lime. We tempered the copious lime juice by paring it back and balancing it with some zest, which lent brightness without any extra sour notes. A seeded habanero added fruity flavor and gentle heat. As everyone does in Senegal, we used a small amount of chicken bouillon—the all-purpose seasoning in sub-Saharan Africa.

The ingredients were whisked together with a bit of water, and in went the chicken and onions. As with most places outside America, whole chickens are called for, but we used bone-in, skin-on chicken parts. We also slightly reduced the amount of onion and tested the recipe with all different types (see sidebar), opting for pungent yellow onions, which turn sweet during cooking.

A couple hours later, the chicken was scooped out of its marinade and patted dry, the onions drained and the marinade reserved. We briefly browned the meat on the stove in a Dutch oven, then removed it and set it aside. The onions were cooked down with some water. After they were soft and browned, we stirred in the reserved marinade and the chicken and let them all braise for about 25 minutes. Finally, the chicken was set on a platter, and a mixture of oil and lime zest was stirred into the oniony base, forming a sweet-and-sour sauce for the meat.

Back in Dakar, I sat on the porch in the soft African night. I was bathed in the familiar and the unexpected: a motorbike passing by, waves on the beach and the scent of cigar smoke followed by an unfamiliar bird call, hushed conversations in Wolof and the taste of chicken and onions that was a correspondence from an older world. Chicken yassa taught us about onions (the harshest raw onion still turns out to be sweet when cooked) and even more about the charms of sweet and sour.

Related Recipes

September-October 2018

Sign up to receive texts

Successfully signed up to receive texts!

We'll only send our very best offers - Like a $15 store credit to start.

By entering your phone number and submitting this form, you consent to receive marketing text messages (such as promotion codes and cart reminders) from Christopher Kimball's Milk Street at the number provided, including messages sent by autodialer. Consent is not a condition of any purchase. Message and data rates may apply. Message frequency varies. You can unsubscribe at any time by replying STOP or clicking the unsubscribe link (where available) in one of our messages. View our Privacy Policy and Terms of Service.