Simple

by Yotam Ottolenghi

Yotam Ottolenghi has done it again. The food is simpler than that of his other books, though you still need a core Middle Eastern pantry for many recipes, a small ask. (Za’atar, harissa and pomegranate molasses are key players.) One favorite is the cherry tomato sauce that uses olive oil and almost a cup of water to cook tomatoes for an hour, reducing their flavor and texture; even store-bought tomatoes yield great results. As with his other books, you realize he thinks about cooking differently: He roasts whole vegetables, uses full-fat yogurt for sauces and deploys spices as game-changers, as in sumac-roasted strawberries. He can jazz up almost anything with a drizzle of herb-infused oil. Some recipes are adventurous (beet, caraway and goat cheese bread), while others are close to home (chopped salad). No matter. Cooking with Ottolenghi is always time well spent.

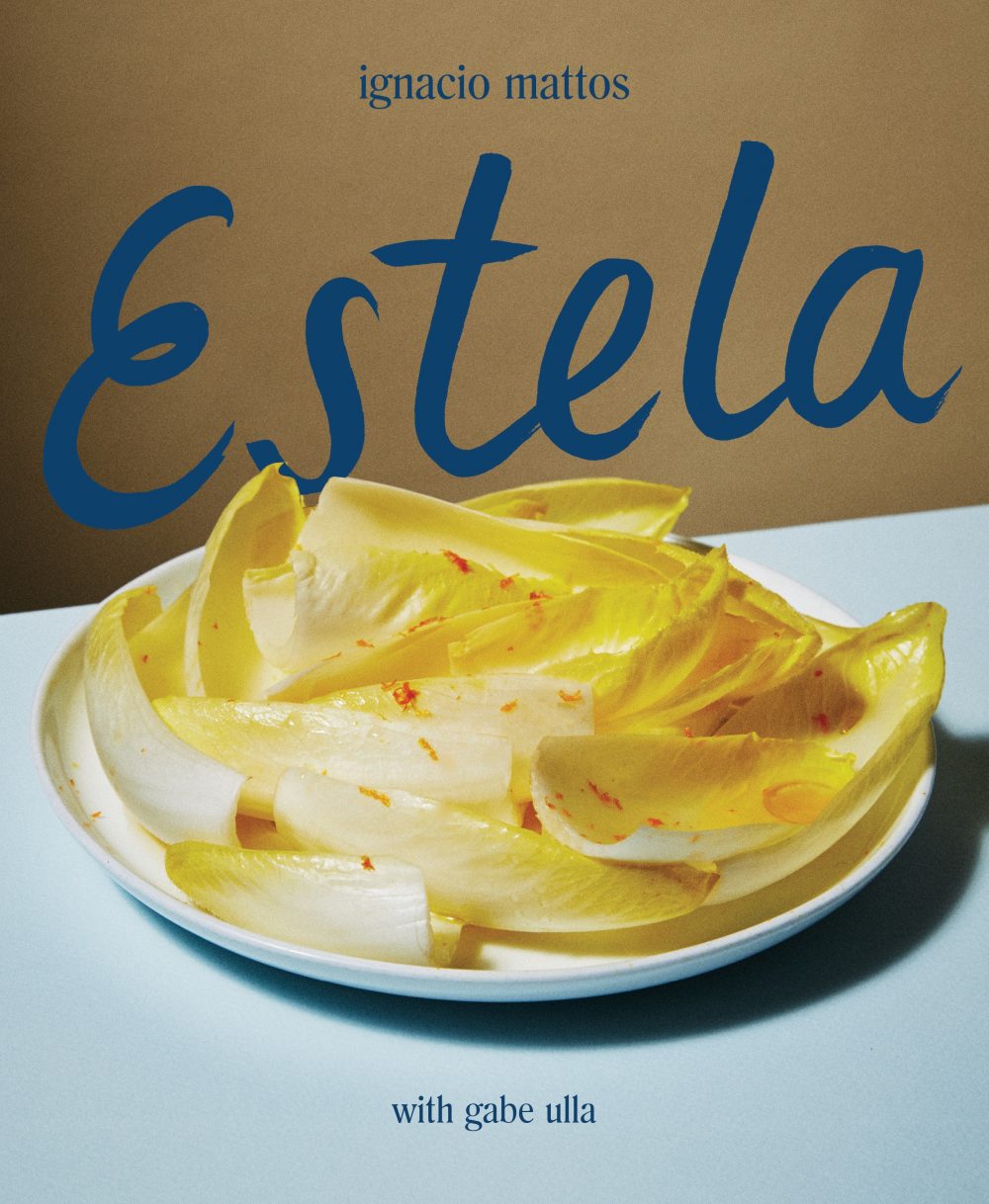

Ignacio Mattos is from Uruguay, where there are 3 million people, 12 million cows and two World Cup trophies. He refers to Europe as the “old continent.” It differs from Uruguay, a place that gives Mattos the freedom to leave the past behind. Trained by some of the world’s best chefs (Judy Rogers and Francis Mallmann, among others), Mattos is a fan of “cucina povera,” cuisine born out of necessity. In “Estela,” named after his New York restaurant, Mattos honors the notion of simplicity—skillet-toasted pumpernickel topped with Brie and tomatoes, or steak served with Brussels sprouts and a sauce of Taleggio and cream. He also gives high-value cooking tips: a few drops of fish sauce provide umami flavor sans fishiness; blend different types of vinegar for complexity; char cucumbers or leeks to add sweet and bitter notes to a dish. Yes, there are restaurant-worthy dishes here, but Mattos knows where he comes from, a place where cucina povera and the freedom to improvise go hand in hand.

Estela

by Ignacio Mattos

Season

by Nik Sharma

Pickles aren’t simple, or so one learns after consuming just a few pages of “Pickles” by Jan Davison. There are quick pickles, pickle pickles and fermented pickles, not to mention dry salting and dry pickling with soybean paste or rice mold, ketchup, hot sauce—you get the idea. The fundamentals are simple: When the pH drops below 4.6, the acidic environment “prevents the growth of food-spoiling microorganisms and eliminates certain food toxins and pathogens.” In other words, pickling preserves. And as with most cured foods, the results taste great, too. Pickles were common 4,000 years ago in Mesopotamia. Romans pickled whole fried fish in hot vinegar. The range of pickled foods extends from mushrooms in Russia, locusts in Persia and herring in Holland to bananas in the West Indies, lemons in North Africa and feta in Greece. In Japan, they quick-pickle chrysanthemums as a condiment. Who knew?

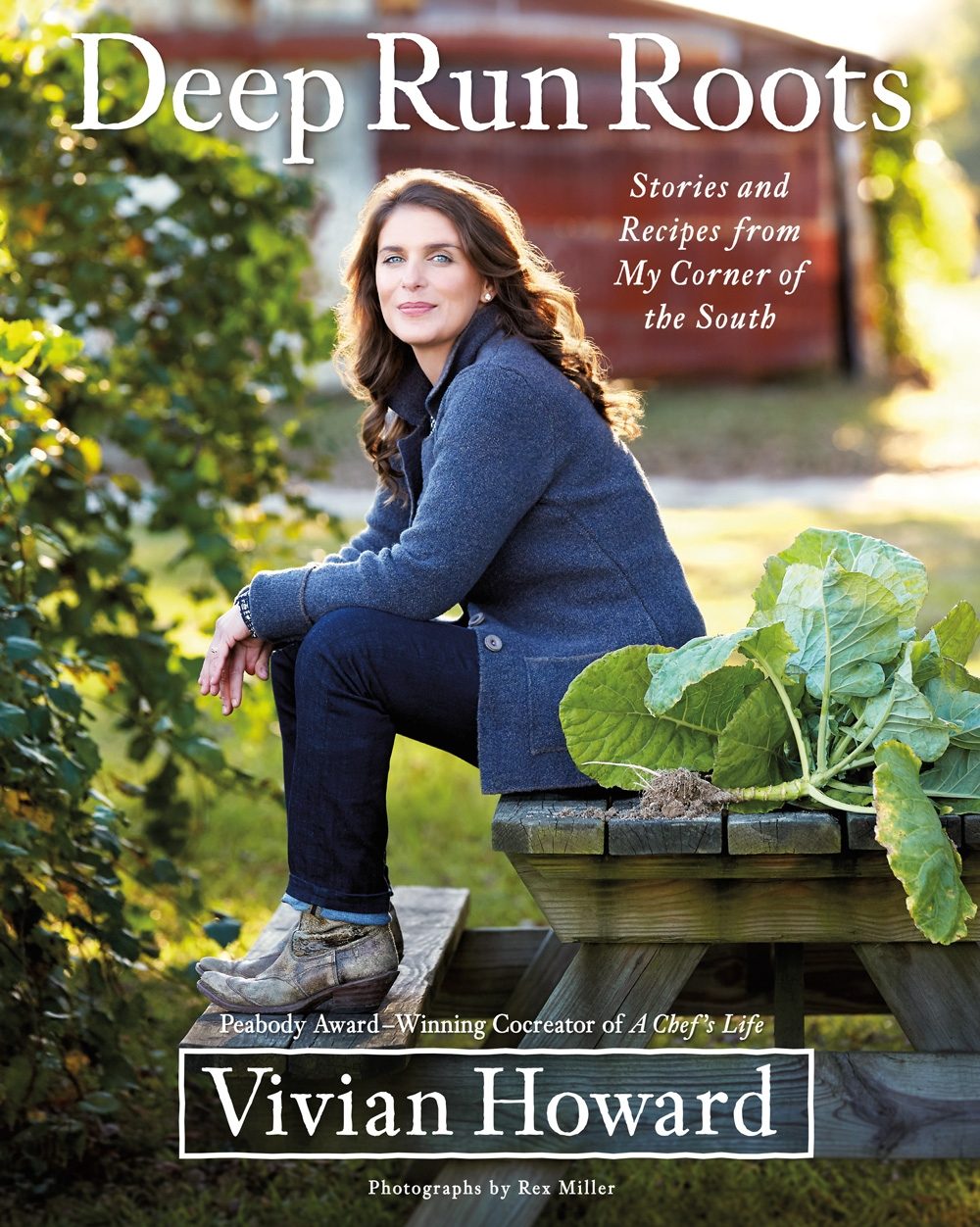

Vivian Howard’s story is not uncommon: New Yorker returns home to her rural roots, lives in a shack and opens a restaurant in a town where Main Street is a collection of shuttered storefronts. After a few years, the restaurant and town become destinations. During an interview with Howard, I realized that this is no made-for-TV movie. Growing up, Howard celebrated Halloween at the Bethel Baptist Church (the houses were too far apart for trick-or-treat), where a cauldron of fish stew bubbled with a scary mix of fish heads, spiny bones, speckled skin and hard-poached eggs. As Howard points out, Deep Run, North Carolina, is not a town; it’s a fire district. Over time, her big-city cooking returned to its roots. It’s no surprise barbecue sauce, spoonbread and pickled watermelon rind, but and a country take on shakshuka (stewed-tomato shirred eggs with ham chips). Best of all, Howard has a strong voice.

Deep Run Roots

by Vivian Howard