This recipe began with a phone call from Harry Smith at NBC. He was doing a story on the Yale Babylonian Collection; they had translated three recipes from Babylonian tablets that date back nearly 4,000 years. “How would you like to cook the recipe for us and I’ll come up with a crew and film it?” That sounded like a crazy, yet wonderful idea.

The original recipe called for mutton, rendered mutton fat (possibly tail fat), red beets and something called kurrat, a Persian chive. The meat is sautéed; onion, red beet, arugula, cilantro, shallot and cumin are added; then beer and water; and, finally, crushed garlic and leek. The dish is topped with a mixture of cilantro and kurrat and sprinkled with “dry coriander seeds.”

From the perspective of Milk Street, this recipe represented the heart and soul of the best sort of cooking. Ingredients are doubled up: Cilantro is added at the outset and at the end as garnish. Alliums are used in abundance and at different times: first onion and, later, garlic, leek and chives. Ingredients often are pounded in a mortar and pestle to release their flavors. And a fresh, herbaceous topping finishes the dish, along with coriander seeds, coarsely crushed.

To better understand 4,000-year-old cooking methods, we contacted Najmieh Batmanglij, author of “Food of Life: Ancient Persian and Modern Iranian Cooking and Ceremonies.” (Though the city of Babylon itself was located in what is now Iraq, the surrounding region of Mesopotamia occupied a wide swath of land that includes parts of modern-day Iran.) Batmanglij looked over the recipe and gave us a primer on ancient Iranian cooking. For example, she explained that blood, called for in another recipe from the tablets, was a common ingredient and that red wine was a good modern substitute. She pointed out that “red beets” were probably turnips (which are common in that region), so we made the switch. And the “dry coriander” means toasted coriander seed. She also mentioned that Persian cooking was based on balancing hot and cold, much like yin and yang, and she suggested adding dried fenugreek leaves to balance the colder elements, a common ingredient in Persian cooking. (We opted to omit the fenugreek since it is not easily found.)

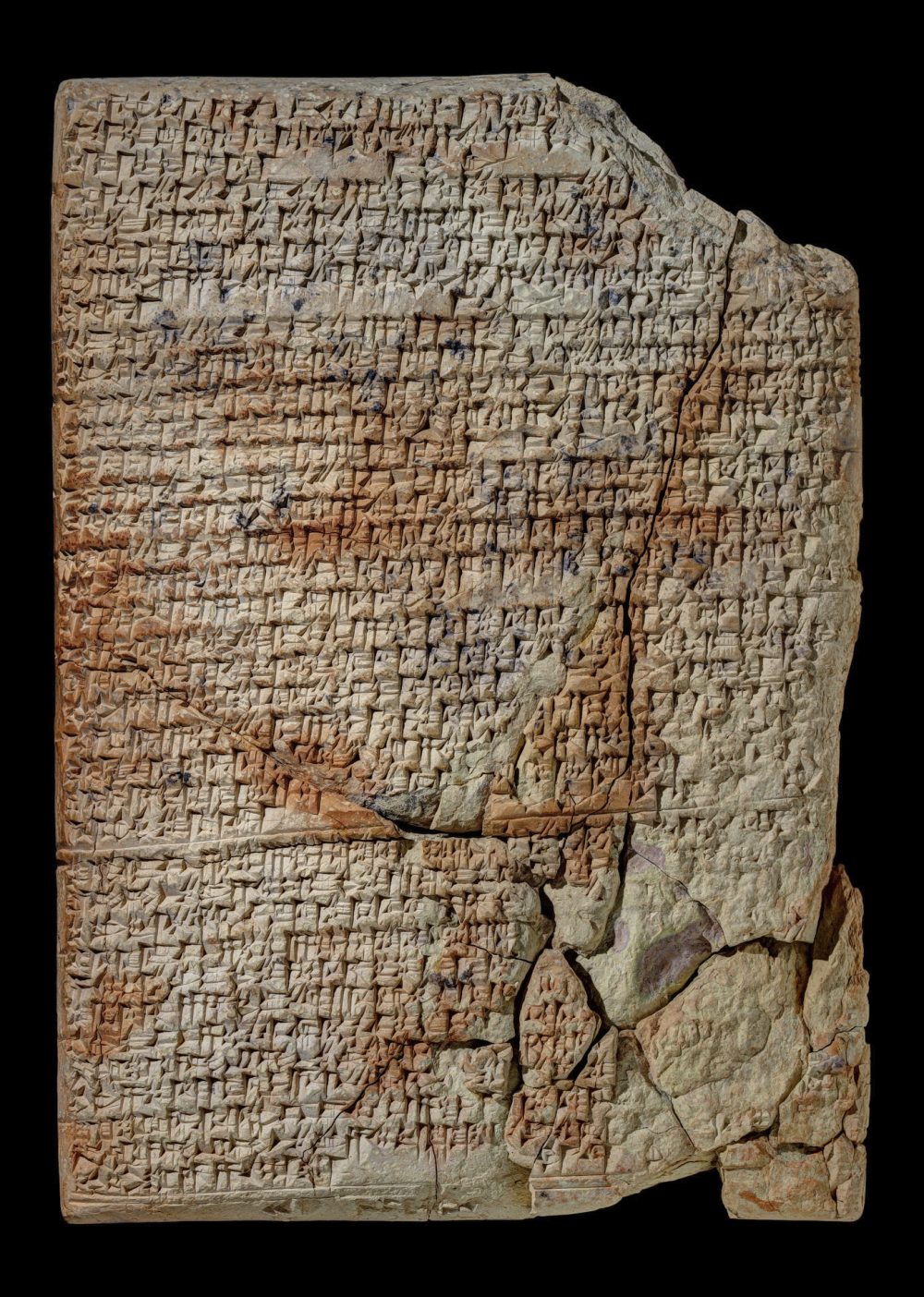

From this ancient tablet, researchers deciphered three recipes: two lamb stews (one made with root vegetables, the other with milk and grain), as well as a vegetarian stew of onions and leeks.

Batmanglij also mentioned that many stews removed the softened meat at the end of cooking, pounded it with cooked grains or legumes, then served it on the side. Another common technique was to use cakes made of hardened grains that were broken into pieces and used to thicken a soup or stew. Our research turned up similarities to some forms of borscht as well as something known as pacha, a lamb stew often made with the entire head.

Of course, trying to decipher a cuneiform recipe from 4,000 years ago has its drawbacks. One obvious problem is the use of now little-known ingredients, including tarru (a bird) and two seasonings called samidu and suhutinnu. Though the cooking methods haven’t changed much, the vibrant flavors of Mesopotamia have been lost to time—who knows how pungent kurrat, their form of chives, was at the time and how it balanced the flavors of the dish? Yale historians also note that most people at the time were illiterate, so cuneiform tablets never were used as ancient recipe cards. Did a scribe sit in a kitchen and dutifully write down “Render tail fat until sizzling”? Why these tablets were inscribed remains a mystery.

Though Babylon was utterly destroyed in the seventh century B.C. by the Assyrian king Sennacherib (who described his victory thusly: “In order that the site of that city and its temples would never be remembered, I devastated it with water so that it became a mere meadow.”), the cooking of an earlier period survives today. We think of lost civilizations as being primitive in both taste and method, but this recipe proves the opposite. Mesopotamia not only was the cradle of civilization, it was home to a host of gourmet cooks as well.