The Man Who Ate Too Much

I first met James Beard in 1979 at his West Village townhouse a few months before I launched Cook’s Magazine. He was enormous, affable and quick-witted, with a twinkle in his eye that belied his passion for all things culinary. Until I read John Birdsall’s well-researched biography, however, I did not appreciate the breadth of his passions and the depth of his disappointments. He was born in Portland, Oregon, in 1903. Summers spent in seaside Gearhart left an epicurean mark: Fried oysters were part of the family tradition, “hissing, foaming, edging into brownness, with a scent so rich it would seem capable of tinting the air gold.” Life soon turned bitter. Beard desperately wanted to be an opera singer and, after being expelled from Reed College (according to Birdsall, because he was gay), he suffered a disastrous audition at the Royal Academy of Music. He did land a nonspeaking role in “Cyrano de Bergerac” and appeared as an extra in a few Hollywood movies. After partnering in a catering business in New York, he finally found commercial success with “The James Beard Cookbook” and his masterpiece, “James Beard’s American Cookery,” which married a conversational style with recipes. He believed that America possessed a cuisine bourgeoise, like France, and therefore deserved serious consideration. His role was put best by Birdsall: “James was a continental gourmet who spoke in American cornball vernacular.” Beard and Julia Child were good friends; Child cooked by the book whereas Beard liked to improvise. Television wrapped Julia in its arms and transported her to international stardom. Beard, having already failed in the performing arts, was once again rejected. That left Beard as an éminence grise, the last of a generation of epicures. Today, his name lives on as an arbiter of excellence in the world of culinary achievement. He never got paid to sing opera, but he was a man before his time; he recognized the significance of American cooking at a time when Child and others were still looking to France for inspiration.

Many authors have had a go at the science of cooking. The problem is balancing hard-nosed science with practical advice and engaging delivery. Enter Nik Sharma. “The Flavor Equation” is not a book for geeks who want a deep dive into amino acids, gels and osmosis—this is a book about how to optimize flavor and, for Sharma, flavor is visceral and complex. It is emotion, sight, sound, mouthfeel, aroma and taste. Flavor is also brightness, bitterness, saltiness, sweetness and savoriness. Sharma teaches us that good food is not about technique per se: It’s about crafting flavor through an understanding of what flavor actually is. Sharma shows us how to make tomato soup, lamb chops, chicken salad, fruit crisp, and spareribs all in new ways by thinking about the push and pull of texture and flavor. This offers a transforma- tional way forward for anyone who wants to grow from good cook to great cook.

The Flavor Equation

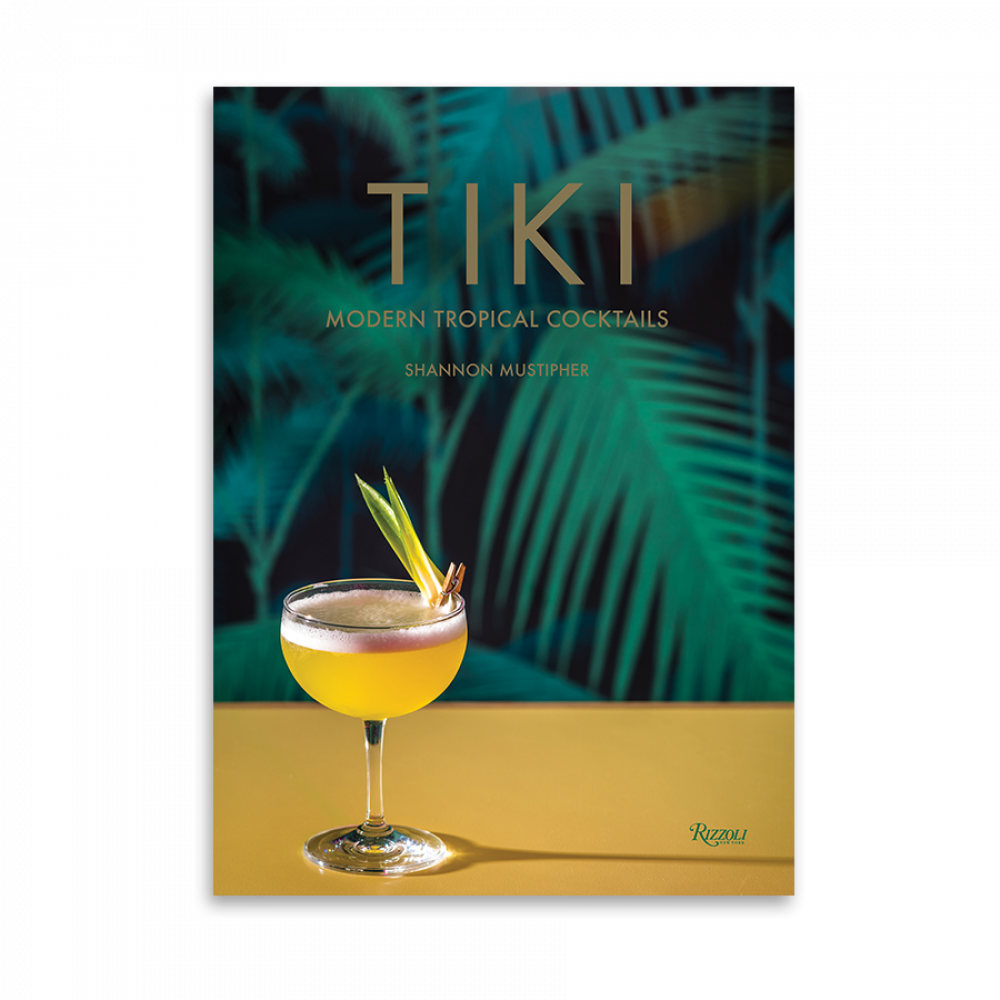

Tiki: Modern Tropical Cocktails

The tiki bar is a fiction, or, as journalist Meredith Heil put it, “Filipino bartenders serving Cuban rum mixed with Indonesian coconut milk in a glass modeled after the heads of Easter Island.” But in “Tiki,” Shannon Mustipher makes clear that the cocktails themselves outlived their origins and became fixtures in bars around the world. Mustipher’s comprehensive knowledge of the ingredients is eye-opening. “Tiki” sings the siren song of such tropical ingredients as banana syrup, soursop juice and falernum (a spiced rum-based infusion). Still, the essence of most tiki drinks is simple enough: sweet and sour, often expressed in a mixture of rum, sugar and lime. Start with a punch or Mai Tai, or venture forth into a Missionary’s Downfall or a Cockpit Cooler. Want to put some fun back into cocktail hour? Try “Tiki” and live a little, even if you skip the crazy glassware.