Agean

In the first pages of “Aegean,” a black and white photo of Marianna Leivaditaki framed by her fisherman father behind her, his arm crooked over her collarbone, provides a clue to the charm and theme of this book: a father/daughter portrait that expresses the unabashed joy of food and family. Crete and the Aegean offer something fresh in the world of food. From hanging octopi on clotheslines to dry, to choosing the best sea urchins, to cleaning snails by putting them into a beehive with dried pasta and flour, “Aegean” feels like a book written about the ancient Minoans. One learns how to make a spicy summer salad with clams and crispy capers and a yogurt, apricot and pine nut dip; serve raw artichokes with lemon and oil; and prepare horta (boiled greens). Buy this book because you want to run away from civilization or because you want to spend a few hours with Leivaditaki and her father in a place out of time. Or, you could just buy it for the food—you will be amply rewarded.

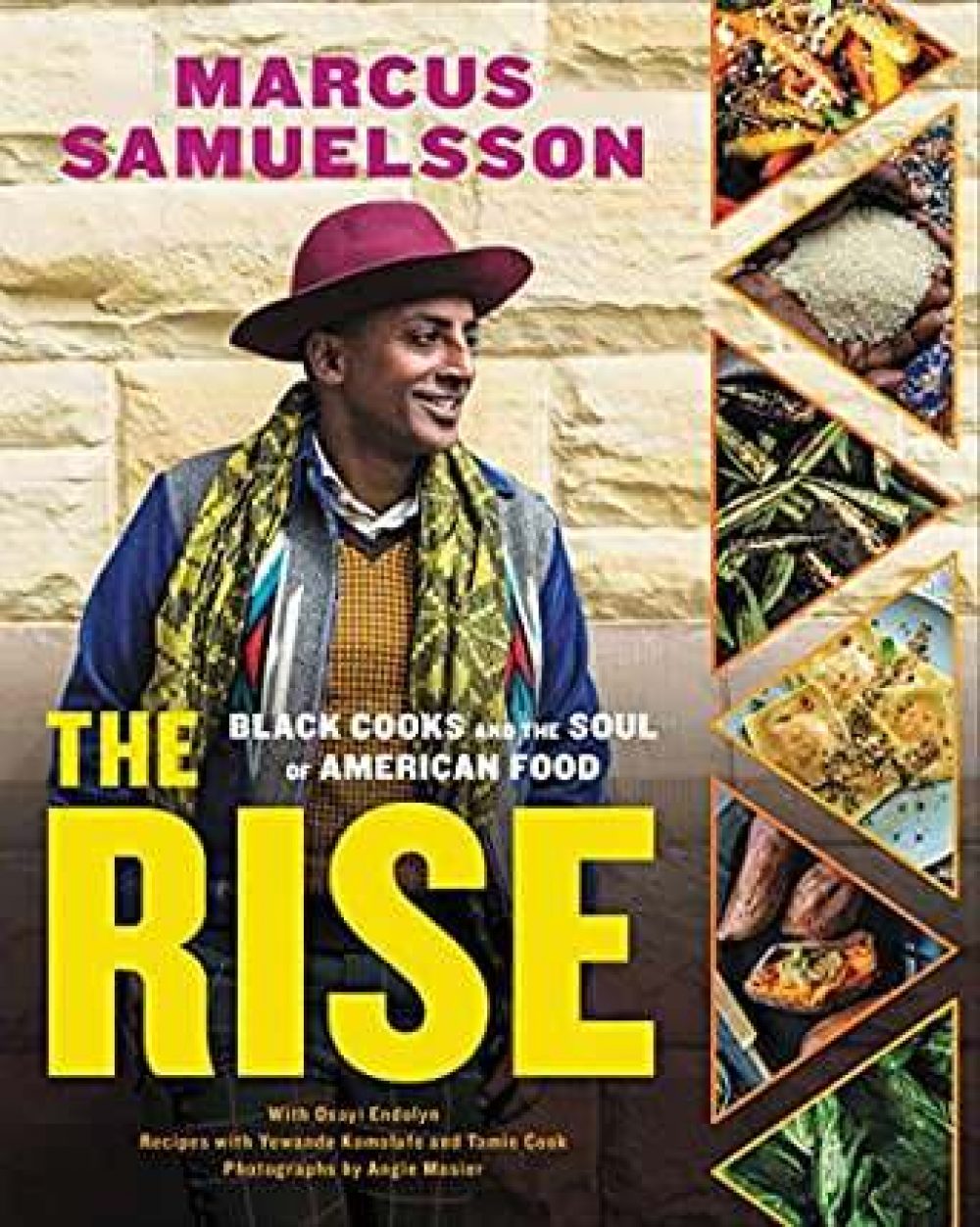

In the preface to “The Rise,” Marcus Samuelsson (Red Rooster chef, winner of “Top Chef Masters” and frequent judge on “Chopped”) asks: “What does it mean to be a Black cook?” It’s a subject that Samuelsson, born in Ethiopia and raised in Sweden before moving to the U.S., is passionate about. Reading this book—which spans kofta with okra, doro wat rigatoni, jollof rice, coconut fried chicken, yassa, pork and beans with piri piri sauce, and sea moss smoothies—one is left with a truly remarkable collection of recipes but without, I think, a clear answer to his question. And maybe that is exactly the point. Black in the culinary sense is about as broad a definition as one can imagine, from Cape Town to Dakar, from Alabama to Chicago, and, in Samuelsson’s case, from Ethiopia to Sweden to New York. There is joy and energy to this cooking; there is a deep sense of terroir married to the great toll of slavery and the chance, often delightful, idiosyncrasies of culinary immigration. Most of all, and I hope that Samuelsson would agree, there is the hope, or the demand, that this abundance of culture and food be considered an essential part of what makes America so special. Samuelsson is proud to be an American; he just wants us to recognize the rich tapestry of our history and the great talent that exists to build an even more compelling future.

The Rise

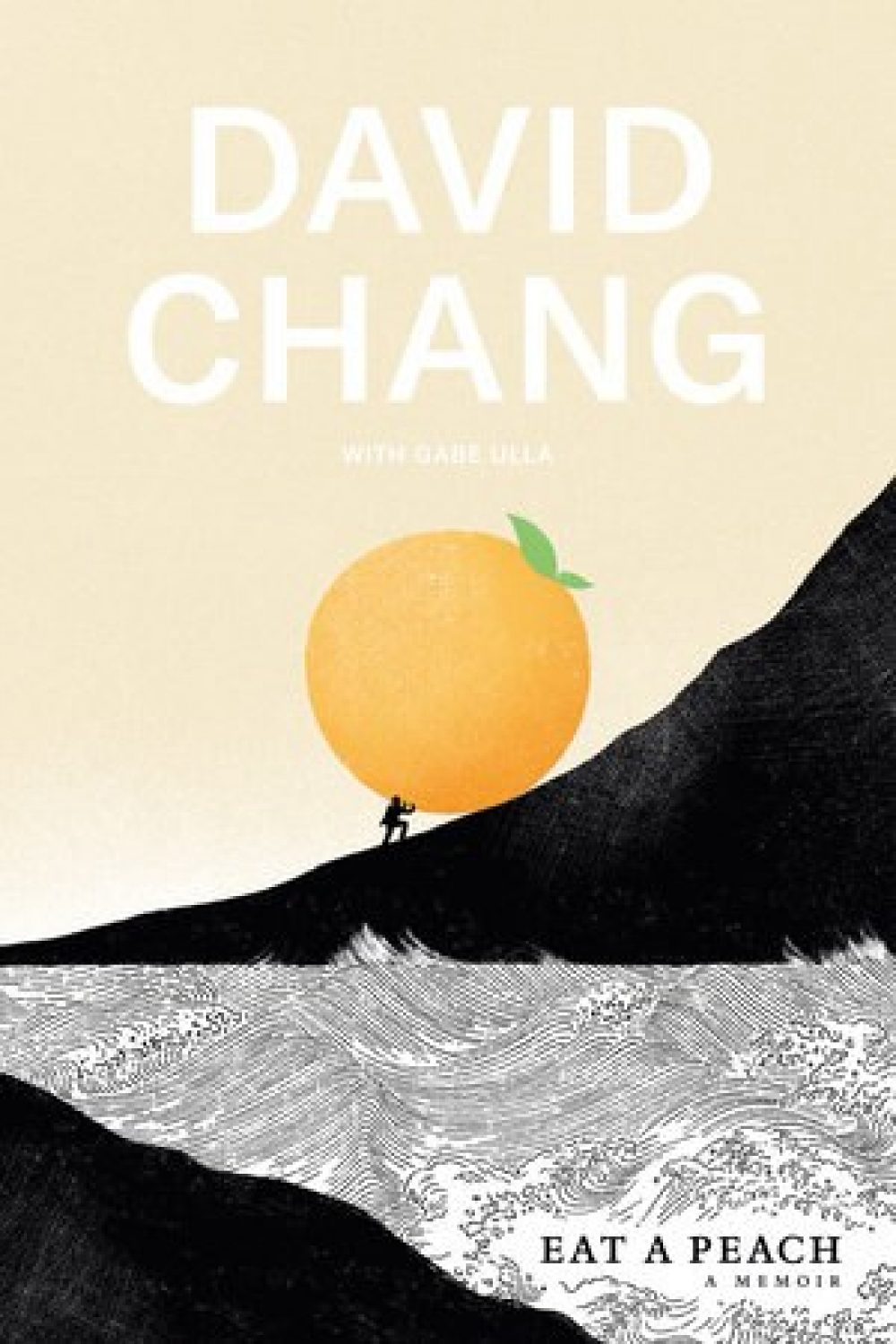

Eat a Peach

I had never met David Chang until a few months ago, and I was pleasantly surprised. I was expecting a superstar celebrity chef, and what I found was a humble, thoughtful human being who freely admits his foibles, his fascination with death and his struggles with depression. He was a golf prodigy before age 10 but quickly lost his edge. He studied religion at Trinity College and says that the Bhagavad Gita changed his life. He launched Momofuku to give New Yorkers good, simple food at a fair price but had to completely change the menu after six months to survive. The restaurant business taught him that sheer stubborn willpower is the way forward, that being a chef also means fixing the plumbing and the air conditioner, and (after being fired from a Tokyo restaurant after a four-month gig) that anything subjective can be taken away from you. Most of all he lives by the mantra “Be a fool. For love,” an email sent by Anthony Bourdain after they had enjoyed a knock-down evening of eating and drinking. Translated, Chang loves food and service, and has no time for others in the hospitality business whose passions are lesser. Every day is an opportunity to add “a new pattern to the fabric of culinary history”— and all this from a man who simply wanted to give New Yorkers good food at a good price. David Chang would say that nothing in life is easy, but that is the way it ought to be. Be a fool. For love.