Agean

In the first pages of “Aegean,” a black and white photo of Marianna Leivaditaki framed by her fisherman father behind her, his arm crooked over her collarbone, provides a clue to the charm and theme of this book: a father/daughter portrait that expresses the unabashed joy of food and family. Crete and the Aegean offer something fresh in the world of food. From hanging octopi on clotheslines to dry, to choosing the best sea urchins, to cleaning snails by putting them into a beehive with dried pasta and flour, “Aegean” feels like a book written about the ancient Minoans. One learns how to make a spicy summer salad with clams and crispy capers and a yogurt, apricot and pine nut dip; serve raw artichokes with lemon and oil; and prepare horta (boiled greens). Buy this book because you want to run away from civilization or because you want to spend a few hours with Leivaditaki and her father in a place out of time. Or, you could just buy it for the food—you will be amply rewarded. (Listen to Marianna Leivaditaki on Milk Street Radio.)

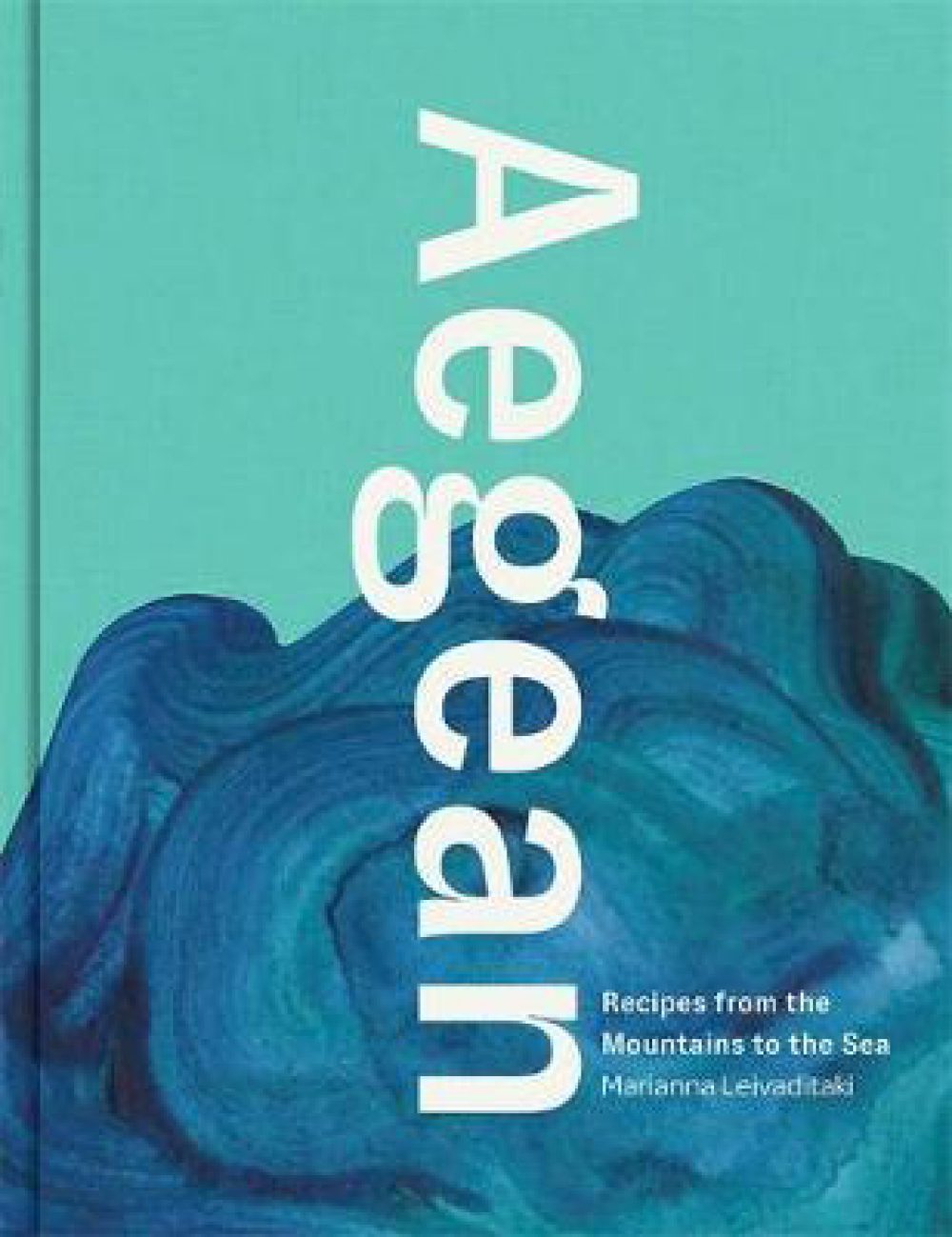

Cool Beans

A few months ago, preparing for a trip to Mexico City, I asked Washington Post food and dining editor Joe Yonan about where to eat, and he waxed poetic about a bowl of beans he had eaten at Eduardo García’s Máximo Bistrot restaurant. That’s it, just a bowl of beans. Two weeks later, I was in Xochimilco, eating those very same beans cooked by García. They were meaty, brothy and slightly spicy. “Cool Beans” delivers this same level of surprise throughout, from coconut cream bean pie to bean ceviche to a spicy Ethiopian red lentil dip. I always knew I liked beans; now I love them. (Read more about Kimball's trip to Xochimilco and get a recipe for those beans here.)

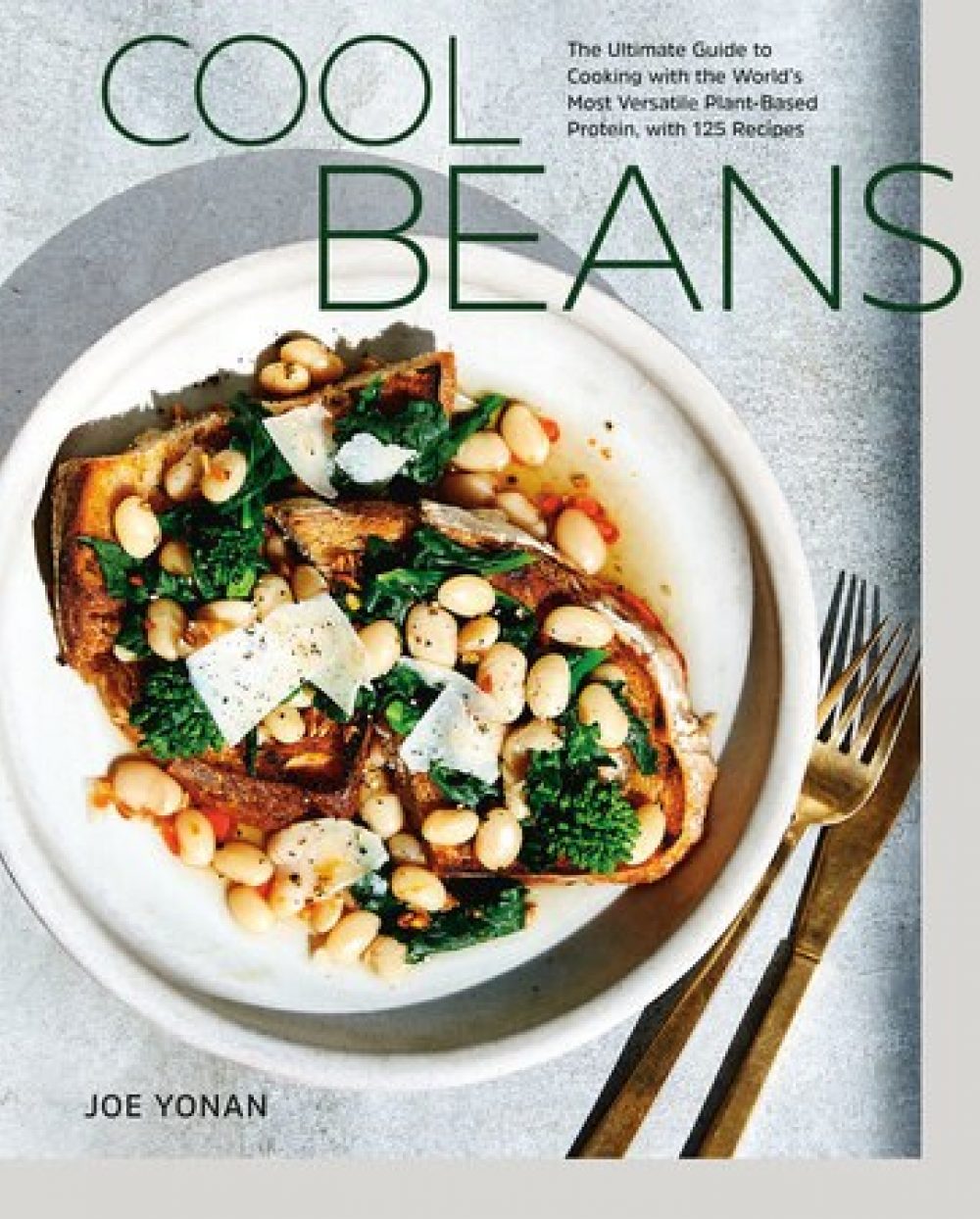

The Rise

In the preface to “The Rise,” Marcus Samuelsson (Red Rooster chef, winner of “Top Chef Masters” and frequent judge on “Chopped”) asks: “What does it mean to be a Black cook?” It’s a subject that Samuelsson, born in Ethiopia and raised in Sweden before moving to the U.S., is passionate about. Reading this book—which spans kofta with okra, doro wat rigatoni, jollof rice, coconut fried chicken, yassa, pork and beans with piri piri sauce, and sea moss smoothies—one is left with a truly remarkable collection of recipes but without, I think, a clear answer to his question. And maybe that is exactly the point. Black in the culinary sense is about as broad a definition as one can imagine, from Cape Town to Dakar, from Alabama to Chicago, and, in Samuelsson’s case, from Ethiopia to Sweden to New York. There is joy and energy to this cooking; there is a deep sense of terroir married to the great toll of slavery and the chance, often delightful, idiosyncrasies of culinary immigration. Most of all, and I hope that Samuelsson would agree, there is the hope, or the demand, that this abundance of culture and food be considered an essential part of what makes America so special. Samuelsson is proud to be an American; he just wants us to recognize the rich tapestry of our history and the great talent that exists to build an even more compelling future. (Listen to Marcus Samuelsson on Milk Street Radio.)

Eat a Peach

I had never met David Chang until a few months ago, and I was pleasantly surprised. I was expecting a superstar celebrity chef, and what I found was a humble, thoughtful human being who freely admits his foibles, his fascination with death and his struggles with depression. He was a golf prodigy before age 10 but quickly lost his edge. He studied religion at Trinity College and says that the Bhagavad Gita changed his life. He launched Momofuku to give New Yorkers good, simple food at a fair price but had to completely change the menu after six months to survive. The restaurant business taught him that sheer stubborn willpower is the way forward, that being a chef also means fixing the plumbing and the air conditioner, and (after being fired from a Tokyo restaurant after a four-month gig) that anything subjective can be taken away from you. Most of all he lives by the mantra “Be a fool. For love,” an email sent by Anthony Bourdain after they had enjoyed a knock-down evening of eating and drinking. Translated, Chang loves food and service, and has no time for others in the hospitality business whose passions are lesser. Every day is an opportunity to add “a new pattern to the fabric of culinary history”— and all this from a man who simply wanted to give New Yorkers good food at a good price. David Chang would say that nothing in life is easy, but that is the way it ought to be. Be a fool. For love. (Listen to David Chang on Milk Street Radio.)

The Flavor Equation

Many authors have had a go at the science of cooking. The problem is balancing hard-nosed science with practical advice and engaging delivery. Enter Nik Sharma. “The Flavor Equation” is not a book for geeks who want a deep dive into amino acids, gels and osmosis—this is a book about how to optimize flavor and, for Sharma, flavor is visceral and complex. It is emotion, sight, sound, mouthfeel, aroma and taste. Flavor is also brightness, bitterness, saltiness, sweetness and savoriness. Sharma teaches us that good food is not about technique per se: It’s about crafting flavor through an understanding of what flavor actually is. Sharma shows us how to make tomato soup, lamb chops, chicken salad, fruit crisp, and spareribs all in new ways by thinking about the push and pull of texture and flavor. This offers a transforma- tional way forward for anyone who wants to grow from good cook to great cook. (Read more from Friend of Milk Street Nik Sharma here.)

The Man Who Ate Too Much

I first met James Beard in 1979 at his West Village townhouse a few months before I launched Cook’s Magazine. He was enormous, affable and quick-witted, with a twinkle in his eye that belied his passion for all things culinary. Until I read John Birdsall’s well-researched biography, however, I did not appreciate the breadth of his passions and the depth of his disappointments. He was born in Portland, Oregon, in 1903. Summers spent in seaside Gearhart left an epicurean mark: Fried oysters were part of the family tradition, “hissing, foaming, edging into brownness, with a scent so rich it would seem capable of tinting the air gold.” Life soon turned bitter. Beard desperately wanted to be an opera singer and, after being expelled from Reed College (according to Birdsall, because he was gay), he suffered a disastrous audition at the Royal Academy of Music. He did land a nonspeaking role in “Cyrano de Bergerac” and appeared as an extra in a few Hollywood movies. After partnering in a catering business in New York, he finally found commercial success with “The James Beard Cookbook” and his masterpiece, “James Beard’s American Cookery,” which married a conversational style with recipes. He believed that America possessed a cuisine bourgeoise, like France, and therefore deserved serious consideration. His role was put best by Birdsall: “James was a continental gourmet who spoke in American cornball vernacular.” Beard and Julia Child were good friends; Child cooked by the book whereas Beard liked to improvise. Television wrapped Julia in its arms and transported her to international stardom. Beard, having already failed in the performing arts, was once again rejected. That left Beard as an éminence grise, the last of a generation of epicures. Today, his name lives on as an arbiter of excellence in the world of culinary achievement. He never got paid to sing opera, but he was a man before his time; he recognized the significance of American cooking at a time when Child and others were still looking to France for inspiration. (Listen to John Birdsall on Milk Street Radio.)

Drinking French

“The French are really good at slowing down and not doing anything in particular, except having something to drink,” says author David Lebovitz of his latest book, “Drinking French.” This appetite for casual drinking began in cafés where street sweepers and intellectuals could sit shoulder to shoulder. Today, the French still celebrate the end of the workday with their “l’heure de l’apéro,” a transition between office and home. This is not about hopping the express train to inebriation—it is a time of gentle intoxication accompanied by snacks and conversation. Lebovitz offers a primer on French liqueurs, from Lillet to pastis (originally an absinthe substitute); he also shares recipes for apéro snacks and DIY infusions. Most of all, you will gain an appreciation for lower-alcohol drinks. My advice? Skip the white wine spritzers and hop on the “l’heure de l’apéro” bandwagon. (Watch Lebovitz make a cocktail from the book here with Christopher Kimball.

The Planter of Modern Life

Louis Bromfield is the author and renaissance farmer you have never heard of but wish you had. He saw action in WWI, moved to France in the 1920s and started a salon at his home outside Paris, which boasted a magnificent garden influenced by his friend and fellow gardener Edith Wharton. Bromfield was the best-known author of his age. He was also Doris Duke’s lover, Humphrey Bogart’s best man when he married Lauren Bacall and Eleanor Roosevelt’s nemesis (he warned her repeatedly of the developing Holocaust). In 1938, Bromfield moved back to his birthplace, Ohio, and purchased Malabar, a 600-acre farm where he reinvented modern agriculture. Though the soil on the former dairy farm was poor, he restored it through years of regenerative farming techniques, making Malabar a vision of how to recreate the world. This “Sinatra of the soil” was dismissed by many as a populist writer of potboiler novels who dabbled in gentleman farming, yet his techniques were revolutionary and are still in use today. Though Malabar has survived as a state park, visitors come for the hay rides more than the history. Today, Bromfield is all but forgotten; “The Planter of Modern Life” is an excellent way to remember.

Dirt

After cooking in Italy for his previous book, “Heat,” Bill Buford gets the travel bug again and heads off to Lyon—not for a six-month culinary stage, but for five years to immerse himself in the brigade system of training that defines every French restaurant worth its Michelin star. He starts his adventure by literally bumping into chef Michel Richard at Union Station in Washington, D.C., then working in his kitchen. After months of navigating the French bureaucracy to obtain a visa (the consulate insisted that he prove French residency first, something out of “Catch-22”), he finally ends up in Lyon. There, he works for a bread baker named Bob, enrolls at L’Institut Paul Bocuse and then toils 15-hour days as a stagier at La Mère Brazier, where his pitiful artichoke- carving technique provokes outright laughter. Despite being terrorized by a 19-year-old kitchen psychopath, Buford falls in love with the structure and rigor of the French brigade system: the proper way to stir, how to make a perfect béarnaise and the importance of hanging on to your knife until the job is done. Buford discovers a soulful happiness in repetitive physical labor, a rare find in the life of an intellectual. As the former fiction editor of The New Yorker, Buford is also an energetic, delightful writer, painting scenes like a first-class impressionist. Describing how to prepare a crab, he writes, “You snip off its head from just behind the eyes, which makes a light plonk when it hits the bowl.” As always, here Buford has a knack for bringing the foibles of the human condition to life with an appetite for the eccentric and an eye for detail. It took Buford five years to research this book, and you can savor every drop of his experience in just a few hours. That’s a recipe for success.

See You On Sunday

New York Times food editor Sam Sifton’s latest book is framed by his belief that there is a sacramental element to Sunday suppers. It’s about gathering around the table not to worship food but to enjoy it. As Sifton notes, his recipes—from garlic bread to grilled chicken with white barbecue sauce—have been “tested on the plates of strangers, offered in peace to people who did not ask what they were eating and who asked for more when they were done. That’s not nothing.” (Listen to Sifton on Milk Street Radio.)