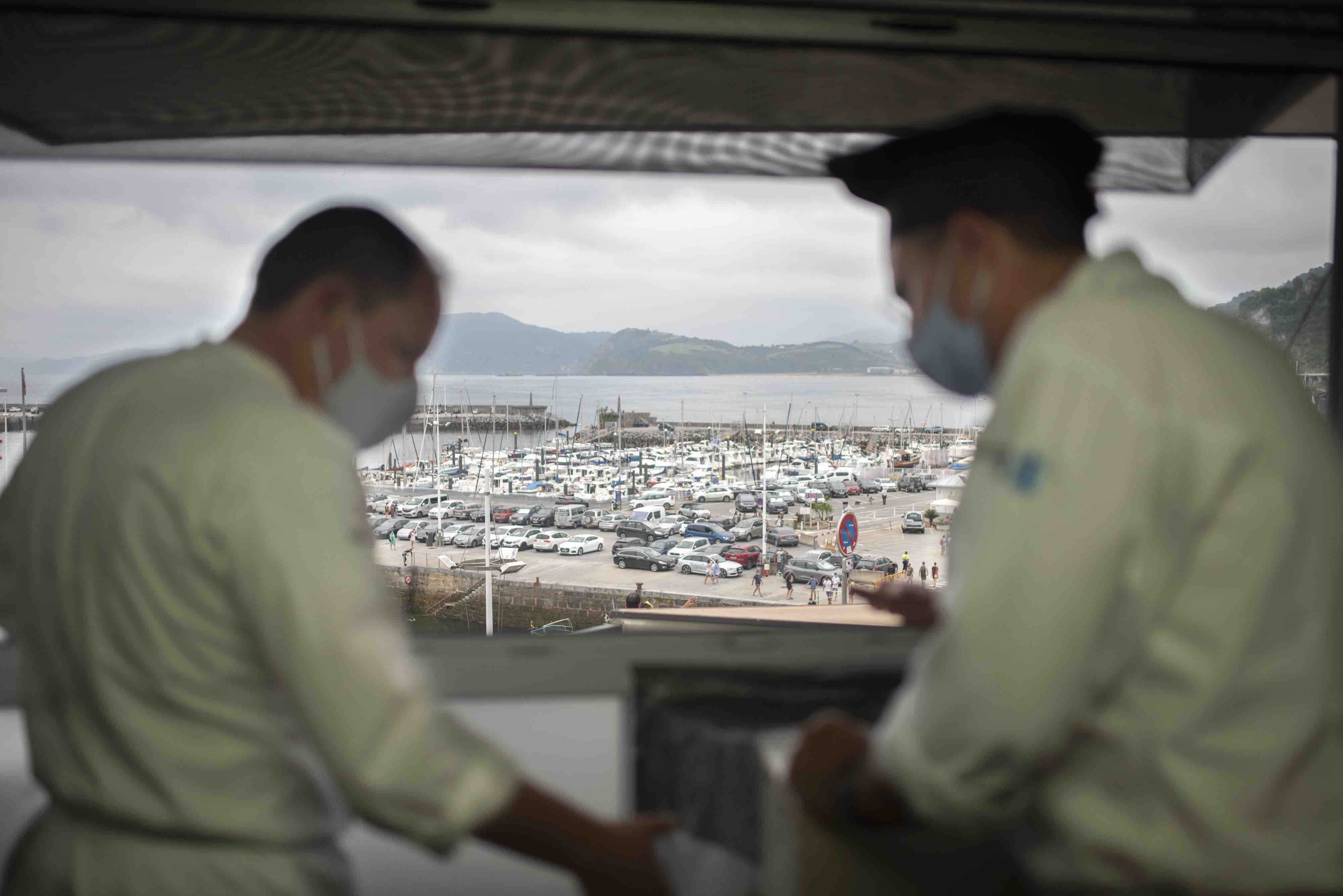

Smoldering wood-fired grills dot the cramped streets of Getaria, built into exterior walls as if restaurants in the fishing village had been turned inside out. White-coated cooks stand on the granite pavers of Kale Nagusia, or Main Street in the Basque language, to squirt basting liquid onto sizzling whole fish.

Each squirt sends up briny aromas of wood smoke, cider vinegar and garlic, enticing diners inside. The skin of the fish blisters as they cook, held fast inside wrought iron cages forged in the shape of the fish for which they are intended—long and tubular for monkfish, ovoid and flat (called a rodaballera) for flounder-like turbot.

Beyond the San Salvador church, its pink and tan sandstone worn over the centuries by fire, war and sea mist, more grills overlook the deep, natural harbor. It was here, at Txoko, that the first grill was put outside in the 1950s, though there were no white coats or any other fine-dining touches back in those days.

“The fishermen were coming here when it was just a bar,” says chef Enrique Fleischmann, who married the founder’s granddaughter. “They sold the drinks and put out a grill so the fishermen could cook what they brought from the boat. They cooked, ate, got themselves drunk and went home.”

Now, the fishermen bring their catch to Fleischmann as often as twice a day, and the town draws a more exacting clientele. They know the prime season for each fish in the rough, cool waters off the northern coast of Spain, and the better restaurants in town treat them with the same nose-to-tail respect as the best American farm-to-table restaurants. Cheeks and heads, livers and egg sacs are as prized as any firm, white flesh.

A waiter with a rodaballera tattoo on his arm—a proud family tradition—helps me remove every last bit of my exquisite monkfish. Grilled whole, the wild-caught, in-season fish is succulent and wonderfully meaty, splashed in a subtle sauce of garlic-infused oil, white wine and vinegar. Washed down with a glass of txakoli, the minerally, effervescent local white wine, it is seductive in its pure simplicity.

More from Spain

But the table keeps filling. Roasted potatoes, stewed peppers and onions, and crispy-creamy ham croquettes. Fresh greens and tomatoes that locals swear are seasoned from the inside, thanks to gardens that soak up the salty air of the surrounding hills. But the star, with all due respect to the monkfish, is merluza en salsa verde con almejas, or a fillet of hake with green sauce and topped with clams.

Salsa verde is a classic Basque sauce, as simple as parsley, garlic, olive oil and white wine. I’d had it elsewhere and was underwhelmed, but this sauce is fragrant and fresh yet somehow rich.

“The hake in green sauce is very traditional but also very much ours— because it’s a different kind of green sauce,” Fleischmann says, and he’s willing to share his secret: The sauce is made in several steps, first from a base made with the usual suspects and enriched with fish bones and guindilla peppers. Separately, a parsley pesto is ground with two surprise ingredients: almonds and a small amount of Idiazabal cheese.

The fish is started on the grill, then poached in a skillet in the base sauce with clams, which release their liquid. The pesto is stirred into the sauce just at the end to preserve its freshness.

“It’s important to note that you don’t notice the cheese, because if you did it would be gross,” says Fleischmann. “Cheese with fish? Come on.”

But it works, delivering a slightly creamy flavor without overpowering the briny brightness of the hake, herbal from the parsley and lightened by the wine.

Once we streamlined the many steps of this restaurant dish into a one-pan meal for the home cook, our salsa verde came out rich from the almonds, cheese and clams, and fresh from heaps of parsley. It pairs equally well with hake or cod, a delicious reminder of the sea breeze in Basque Country, but with just a few steps.