What is soul food? For Alice Randall and Caroline Randall Williams, authors of the award-winning cookbook “Soul Food Love,” the answer cannot be described in a few simple words. Much like the Black American experience itself, soul food is ever-evolving. It can represent struggle, triumph, pain and celebration. It is centuries of history deep-rooted in the soils of two continents, its connective ties stretched thin, but never broken. And though it is difficult to pinpoint exactly what soul food is, it is far easier to define what it is not: uncomplicated.

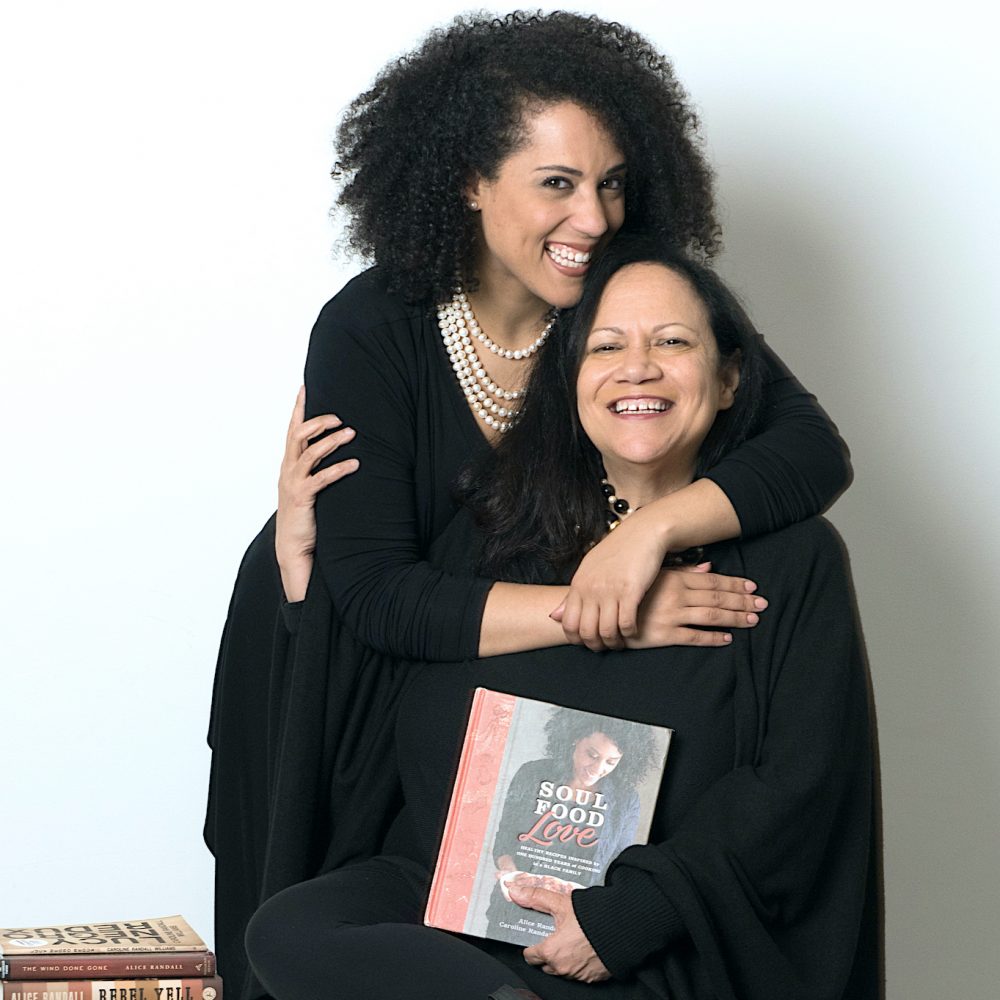

During a recent conversation on Milk Street Radio, the mother-daughter writing team sat down with Christopher Kimball to discuss food, family history and the role soul food has played in shaping America. Get a small taste of the interview from the excerpts below—then listen to the full interview on our website or Apple Podcasts.

On soul food’s deep roots in the American South

Alice Randall: To be Black, and in the South and in America. [When] you look at a tree, when you look at a field, you're not just seeing food, you're seeing stolen labor, and you're seeing terror of lynching. And so, that story is complicated. [Randall Williams's] Grandma Bontemps [established a beautiful home in Harlem] with her husband, and traveled to Yugoslavia and stayed at Tito's palace, [but] she still remembered the turpentine camps of Waycross, Georgia. You take those food memories with you, the good and the bad.

Caroline Randall Williams on why Black American foodways are “plain broke down”

Caroline Randall Williams: I'd never really experienced, in any meaningful, sustained way, a food desert before. I was teaching at a school that was 98 percent Black and comparable figures [could] describe the number of students who [were] living at or below the poverty line. These were kids who were raised with, in some ways, a sense of what soul food was, what Southern food was [and] what Black food was, but then you look around at what food they had access to, and the nearest grocery store was not [within] walking distance. There was irregular transportation, [so] they couldn't get to fresh [or] high quality food. And so, then it becomes things like Popeye's and gas station fried chicken {that] join the narrative of what soul food is. In social ways and cultural ways, those are important additions, but in terms of actually knowing our history and where our food comes from and what it was made of, that's so far from it. And the fact that my students didn't know that it was so far from where we started...that was the “broke down“ part.

Randall Williams on working to redefine her students’ perception of soul food

CRW: I used to bring baked chicken or baked fish to lunch most days at school with some kind of vegetable, which is something I learned from my great grandmother, who was a Black woman born on the plantation where her family had worked for generations in Waycross, Georgia. And my students said to me one day, “Miss Williams, you eat like a white girl,” and I said, “No, I eat like an old Black lady.” And the fact that that divide, that exchange, happened was very illuminating for me, for mom, for a lot of us.

On Black domestic service and creating a safe space

AR: One thing about the Black experience and domestic service, including in the period of enslavement, is that Black people developed an extraordinary grammar of cooking skills. I like to say they saved the best for themselves [...] for their own homes. Grandma Bontemps is an extraordinary example of being on both sides of the the eating, cooking and cleaning equation, and making the most magnificent meals in those settings.

CRW: It's not just saving the best for themselves but also, the other side of that coin is, choosing to have a lovely thing and make your own way into a lovely space when the world is not making that kind of loveliness available to you. What do you do when you want to go out to dinner [or] lunch with your friends, and no restaurant will open its doors to you because of the color of your skin? You find and make a way to have a lovely, elevated experience with your friends and yourself if the world won't give it to you.

On Grandma Joan Bontemps helping to fuel the Civil Rights Movement

AR: Here's a woman whose husband is a librarian and academic at historically Black colleges, not making much money. She had 36 place settings of silver that she hid in the bookshelves of his library behind his books, and would set up these card tables for her friends. She could sit 36 down to dinner. And one of the things that Caroline has inherited is 18 place settings of real Burgundy silver that have been up in Harlem and had been in Tuskegee before that. This is silver that Malcolm X and Adam Clayton Powell have eaten with - these forks and these knives. That's how important laying the beautiful table for our community was for our community, when we could do that.

CRW: She worked as a librarian and brought home money that allowed her to lay these tables. She chose a life with a man who fought for civil rights with every bone and breath of his body, and she was proud to be able to have a job that allowed her to welcome the people that he was working to protect and support. And, to take a worry off of people [who] were coming into her home, [to] just allow them to sink into a moment of celebration or respite. That, to me, is the charge that I feel like I've inherited. I always want my home to be a place that people can come and expect to be taken care of.

On her grandmother’s cookbooks

CRW: [While] writing “Soul Food Love,” Mom and I actually put our hands on every single one of the cookbooks that I inherited from my grandmother. They came in boxes when she passed away. and what was extraordinary is that my grandmother would press flowers into the pages of these books, save menus that she'd written, have a grocery list or little diagrams of how she'd be planning to rearrange the furniture if she was having a lot of people over. My favorite was there were all of these card catalog cards from whenever she'd be reading one of her cookbooks while she was working in the library and have stuck a card catalog card in there to hold her spot, and then have left it. So, as a grown woman myself, getting to know her as a woman, instead of just knowing her as my grandmother, that was a pretty amazing learning experience for me, I'd say.

On the concepts of Diddy Wa Diddy and the Welcome Table

AR: Diddy Wa Diddy is sort of heaven-on-earth in Black folk culture. Zora Neale Hurston is one of the people who captured this. When people dream of heaven, it often reflects what's missing in their world. In the desert, heaven often has water. [In this version of] heaven-on-earth, Diddy Wa Diddy, this mythic place, the chickens ran around with forks and knives in their backs. It was an abundant food world.

In the Black experience, we have the Welcome Table, [based on] one of my favorite hymns, “The Welcome Table.” It's about this great conversation and food at a table. And the table is where we're going to eat milk and honey, but [it's] that idea of milk and honey and conversation. It's an ideal that we're all trying to achieve in secular circumstances now.

Quotes have been edited for clarity.

See here for more from Milk Street Radio, and join the conversation on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and Pinterest.