The Arabesque Table

Muhammara notes that Arabs were almost the only people in the world writing cookbooks between the 7th and 13th centuries and yet, today, their share of the cookbook shelf is unaccountably meager. Fortunately, Kassis (author of “The Palestinian Table”) is here to help. For starters, “The Arabesque Table” makes the point that a national cuisine is a relatively modern concept, one that is deeply flawed. Food is about culture and ethnicity more so than political boundaries. And Arab civilization should be given its due. For example, vegetarian cooking, which dominates the Middle East, has its roots in a time of poverty, when meat was hard to come by. Thickened milk desserts such as blancmange have their roots in similar desserts introduced in the Middle Ages by traders. And, of course, there is the spice trade. The food seems immensely relevant to today’s kitchen, from pomegranate molasses-roasted chicken and quick pickles to such variations on the classics as roasted beet muhammara. And pantry ingredients—sumac, za’atar, freekeh, labneh and shattah—get a good culinary workout. Thanks to the work of Yotam Ottolenghi, Anissa Helou and others, this food feels both familiar and exciting, the perfect recipe for cookbook success.

Hooni Kim left Korea when he was 3 years old. Each year, he and his mother would make the three-day journey from London to the island of So An Do to visit his grandparents, a trip that culminated in a ride on a rickety 12-foot boat. From these beginnings, he attended the French Culinary Institute, worked at Daniel in NYC, then trained in a Japanese restaurant, Masa, because there were no high-end Korean restaurants available. He went on to open his own establishments, Danji and Hanjan, the latter devoted to the Korean culture of communal drinking and anju, the food served alongside the alcohol. Kim takes his experience and offers it to the curious home cook. “My Korea” is a doorway into Korean cooking, from the foundational three “jangs”—gochujang, doenjang and ganjang— to chicken skewers, beef brisket bulgogi sliders, all sorts of barbecue, and noodle dishes such as bibim naengmyeon (spicy cold noodles). This is bold food that suits the full-flavored American palate. As Maangchi, a Korean cook and YouTube star once told me, after three days in France she craved the big flavors of Korean cooking, and you will, too.

My Korea

By Hooni Kim

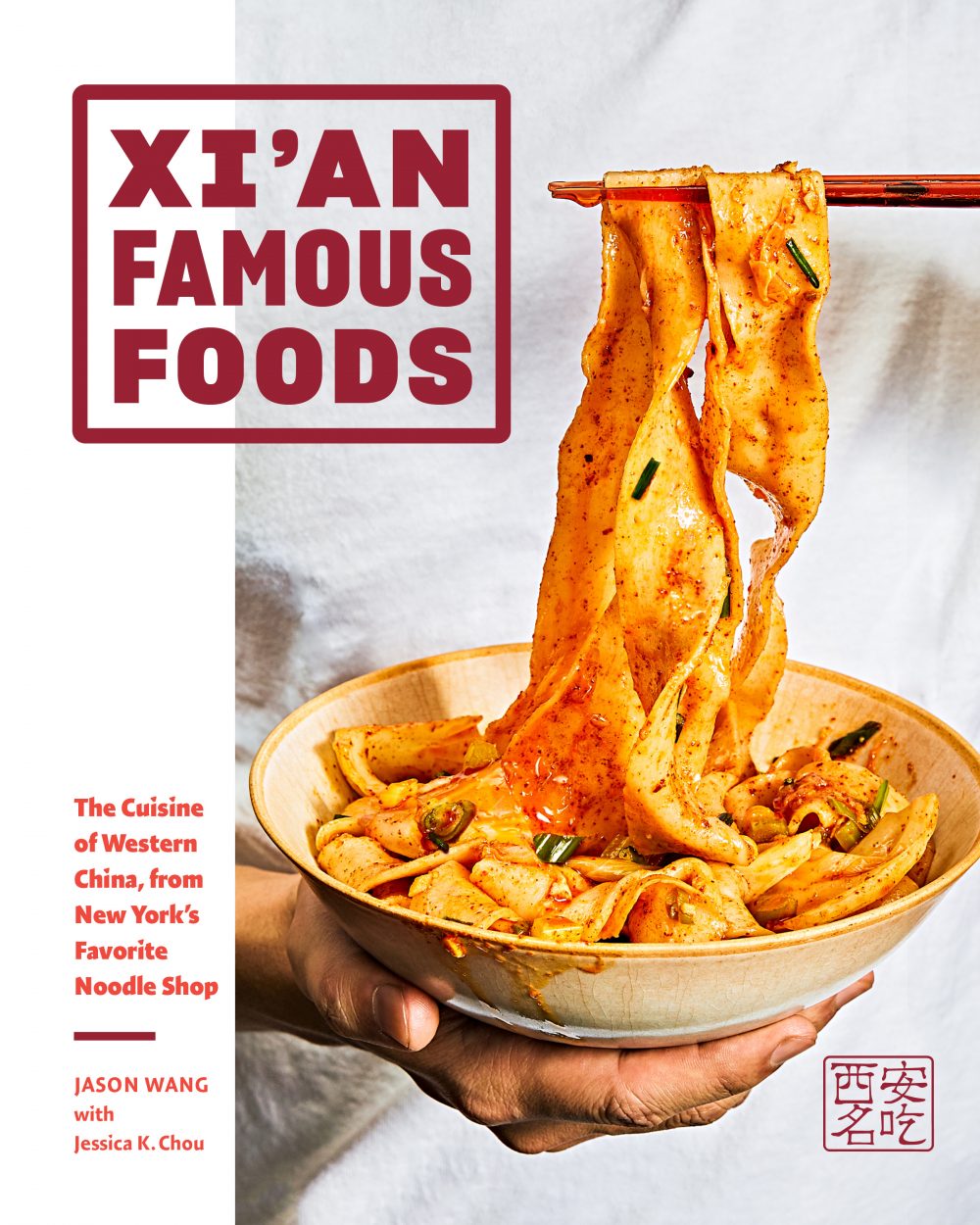

Xi'an Famous Foods

By Jason Wang

Jason Wang’s family moved from Xi’an, China, when he was 8. In 2005, his father opened a bubble tea shop in Flushing, Queens, but added liang pi (cold skin noodles) to the menu. From there, he opened Xi’an Famous Foods, which soon drew visits from Anthony Bourdain and Andrew Zimmern. Today, it has 10 locations— an American success story. Xi’an food offers many culinary lessons: Spice is used for fragrance, flavor and depth, not just heat. Cumin and black vinegar also are key, along with Sichuan peppercorns and soy sauce. (Wang refers to this style of cooking as a blend between xiāng là, fragrantly spicy, and suān, sour.) It’s a master class in layering flavor. Noodles— including longevity noodles and biang-biang (hand-ripped) noodles—play a big role. But Wang likes to innovate as well. He likes to play with the familiar: instant ramen with chili oil, black vinegar, egg and bok choy; chicken and beef skewers; dumplings; and “dry pot” chicken. You also will confront the unfamiliar, including gizzards, beef tendon, pig intestines and mung bean jelly. What I love about “Xi’an Famous Foods,” and many of today’s best cookbooks, is that cookbook editors’ long-held desire to protect home cooks from the gnarlier aspects of “ethnic” cooking is being shouted down by a new crop of cooks who refuse to Americanize their cooking. Good for them. And very good for us.