Tava: Eastern European Baking and Desserts from Romania and Beyond

By Irina Georgescu

In 1971, I took a train south from Budapest to Sibiu, Romania, in search of the burial place of Baron Frank von

Frankenstein, said to have been executed by Vlad Dracula (otherwise known as Vlad the Impaler) in the 15th century. This wild rumor, much to my delight, was true—we found his crypt in a local church. We then hitchhiked to Bucharest, where we were followed by the not-so-secret police. Fast-forward half a century, and I found myself chatting with Irina Georgescu about the charms of Romanian baked goods. How times have changed. Romania is a constellation of cultures; the kitchens are layered with Jewish, Turkish, French, Italian, Saxon and Hungarian influences, among others. And so you find plum pies, Swabian poppy-seed crescents, Linzer tarts, strudel, meringues and gingerbread, with all the glamour of famous Eastern European pastry shops. I was particularly intrigued by pies that feature two unconnected layers—one on bottom and one on top. Fried doughs also are popular, including doughnuts and fritters. Then there are cakes, rhubarb and diplomat. A country that once encouraged Saxon migration to defend its borders and survived the harsh rule of communism, when bribes were made with livestock, Romania deserves to be visited for its food, not the vampires. “Tava” is an excellent start.

Buy on Amazon

Filipinx: Heritage Recipes from the Diaspora

By Angela Dimayuga

There is growing interest in the world of dishes born out of diaspora, recipes that may have started in the homeland but have been adapted over time to new surroundings. Angela Dimayuga grew up in San Jose eating steamy rice, sinigang (a sour tamarind soup) and arroz caldo. The world of Filipino cooking is based on sweet, sour, salty and fat, but often is misunderstood. Dimayuga uses adobo to make the point: Her adobo sa gata starts with peppercorns cooked in coconut oil, followed by chicken, garlic, coconut milk, vinegar, chilies and water. Fried chicken is steamed first, with raw rice used for a marinade. Dimayuga notes that curry probably was introduced to the Philippines through Indian cooks who served in the Royal Navy, while Filipino oxtail peanut stew may have West African roots. The Philippines is home to almost 200 native languages and dialects, 7,000 islands and highly diverse culinary regions. The charm of this book and others like it is that we can stop judging recipes on authenticity and accept that food changes as people and cultures move and mix. It’s what makes “Filipinx” an adventure.

Buy on Amazon

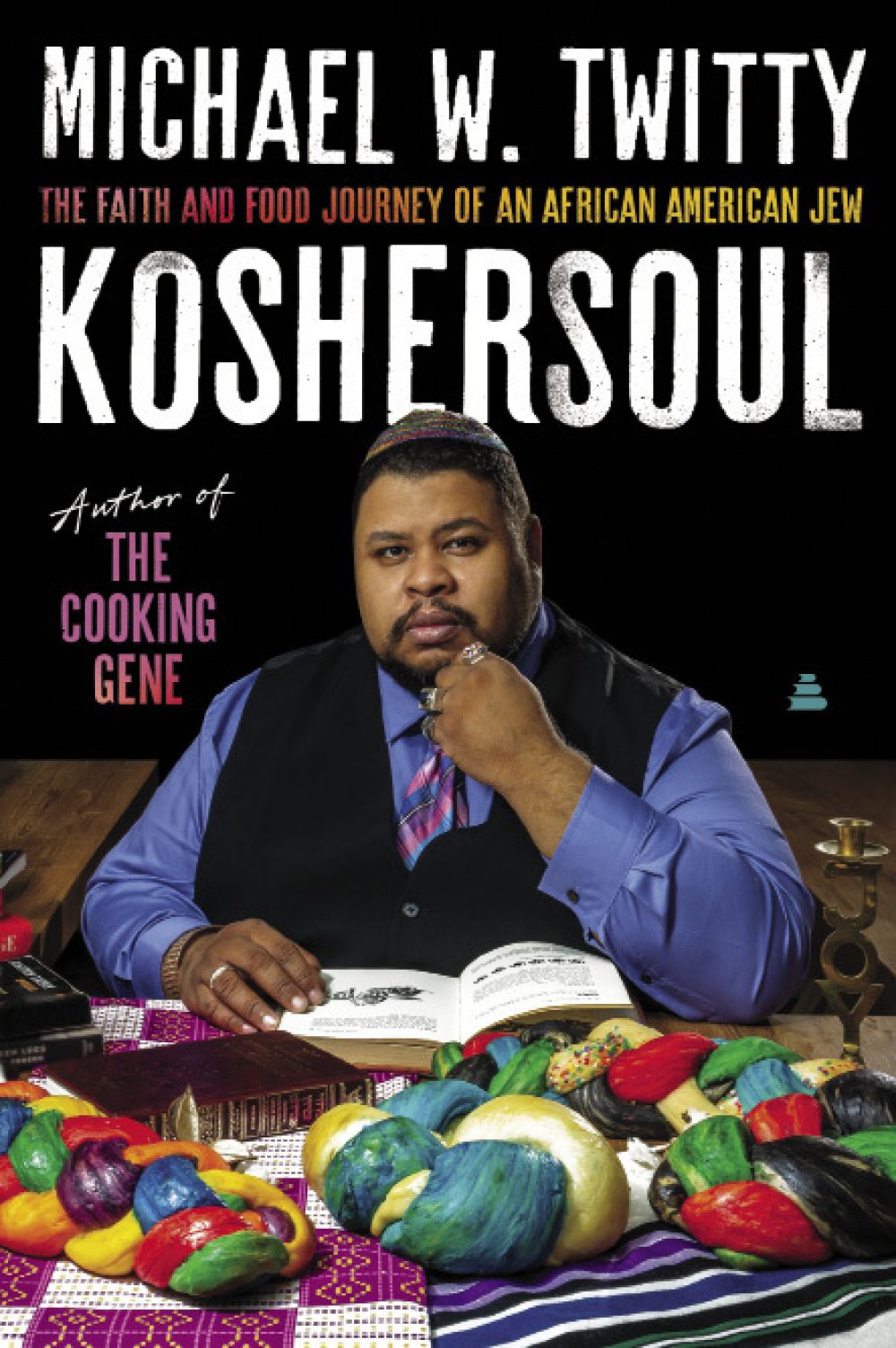

Koshersoul: The Faith and Food Journey of an African American Jew

By Michael W. Twitty

Michael W. Twitty is no lightweight as an intellectual, a historian or a storyteller. He investigated his own cultural DNA in “The Cooking Gene” using a literary construct that was both thoughtful and thought-provoking. In “Koshersoul,” he takes a similar journey but starts with his combined Jewish and Black heritage and then asks what they have in common. His answer is, “Jewish food is where we can flourish because of the centrality of humor and joy in both traditions—African and Jewish Diasporas—of beating back trauma through brave happiness.” Whether there really is a meeting of these divergent culinary traditions may be another matter—Louisiana-style latkes or collard green kreplach—but Twitty is looking for something deeper, how two cultures forced into wide-ranging diasporas dealt with hardship through food and tradition. He finds humor and joy in both places, which turns this book from the dark side of suffering into the hopefulness of a joint culinary future.