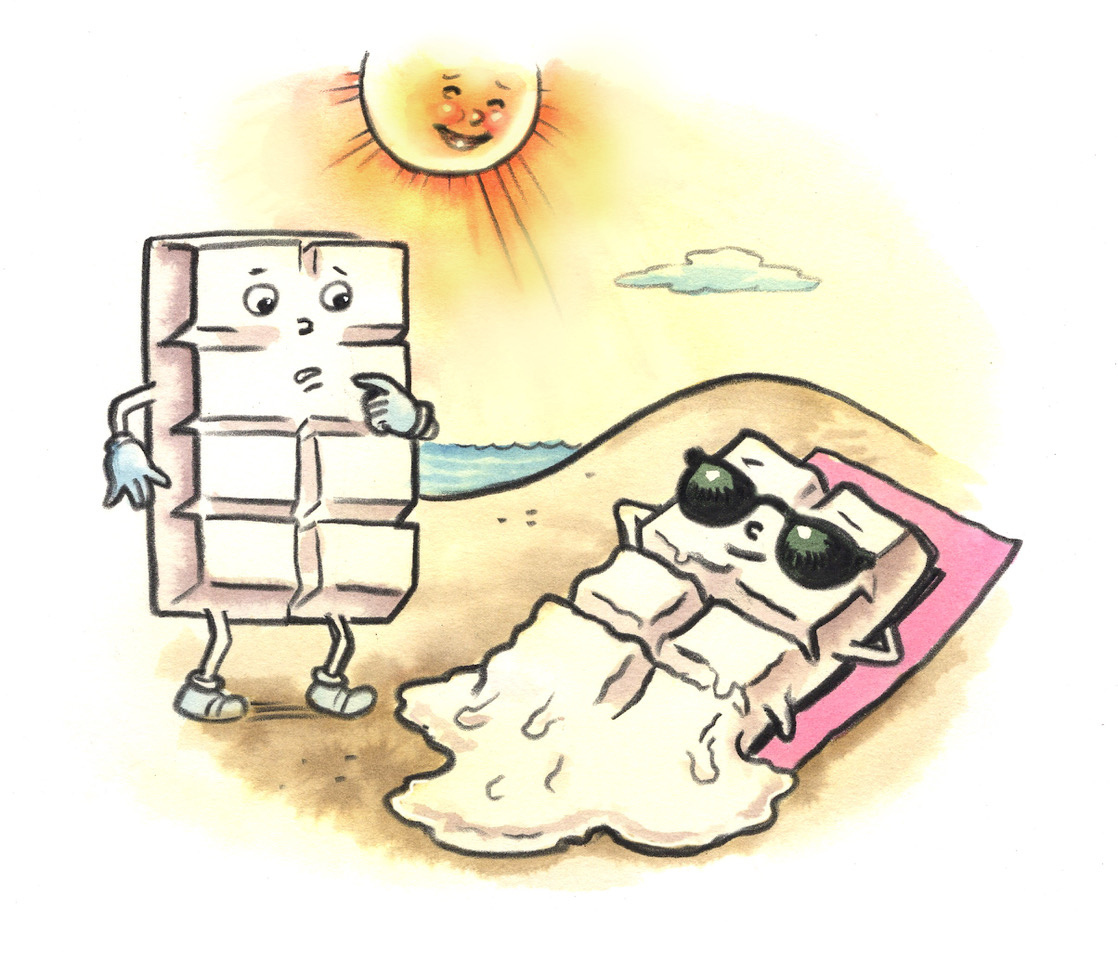

White Chocolate Woes

Lorien Wilson, of Loudon, New Hampshire, loves baking with white chocolate, but is frustrated by unpredictable results. In cookies, it behaves fine, but in scones it often melts away. She wondered what is happening.

Since it melts more easily than milk or dark chocolate, white chocolate can be tricky to bake with. This is because white chocolate contains no cocoa solids, only cocoa butter (the flavorful, creamy-colored fat extracted from cacao), which has a lower melting point. But not all white chocolate is created equal. In the U.S., white chocolate need only contain at least 20 percent cocoa butter, so many companies blend it with less expensive palm oil. Further complicating the matter, some “white chocolate” isn’t chocolate at all. Products labeled “white baking wafers,” “white morsels” or “white melting chips” contain no cocoa butter and are made entirely of palm oil. These products tend to hold their shape better during baking because palm oil is more stable at room temperature than cocoa butter. In other words, the greater the purity of white chocolate, the more prone it is to melting. To successfully bake with quality white chocolate, you need to consider several factors—the time and temperature called for in the recipe, as well as the moisture and fat content of the baked good. After numerous tests and a consult with baking expert Stella Parks (author of the “BraveTart” cookbook), we found that longer baking times and higher heat increased the chances of white chocolate melting into the dough. And doughs with higher moisture content tend to bake longer than drier baked goods. This would explain why Wilson has more success with cookies, which usually bake for less time than scones. Location matters, too. In our testing, white chocolate chunks embedded in scones always melted, but those on the exterior tended to fare better. Parks suspects that’s because they are less exposed to the dough’s moisture. To fix this, she suggests trying a lower-moisture recipe and using larger chunks to minimize surface area. Setting some white chocolate aside to press into the surface of the scones may help, too. Or simply reach for the cheaper stuff—white chocolate chips may not contain as much cocoa butter, but they’re more likely to hold their shape, with little noticeable difference in flavor when used as a mix-in for baked goods such as cookies or scones.

Beef Stock Rebound?

Maureen Doherty, of Atlantic, Iowa, makes stock by roasting meaty beef bones, then simmering them in liquid for many hours. This produces plenty of stock—but also several pounds of leftover meat. Not wanting to be wasteful, she wonders: Can this meat be used in other recipes?

Meat rendered while making stock often is discarded, as the cooking process extracts most of its savory richness. But this leftover meat is still fine to eat—you just have to compensate for its flavor deficit. The easiest solution is to douse it in a bold sauce, be it a bright tomato sauce or a deeply savory gravy. For example, the Mexican culinary canon offers many approaches that can transform long-simmered meat. Try making it into salpicón (a tangy salad of shredded beef and vegetables) by tossing the meat with a spiced vinaigrette and serving the mixture in tacos or atop tostadas. Or treat the leftover meat like machaca (a type of dried, shredded meat) by cooking it with scrambled eggs and topping it with salsa. We also like it served in a cream sauce with popovers—a recipe recently recreated on Milk Street’s My Family Recipe, our new television program on Roku. For that recipe, go to 177milkstreet.com/jf23-popovers.