Your email address is required to begin the subscription process. We will use it for customer service and other communications from Milk Street. You can unsubscribe from receiving our emails at any time.

Pease Porridge Hot

Back to November-December 2017

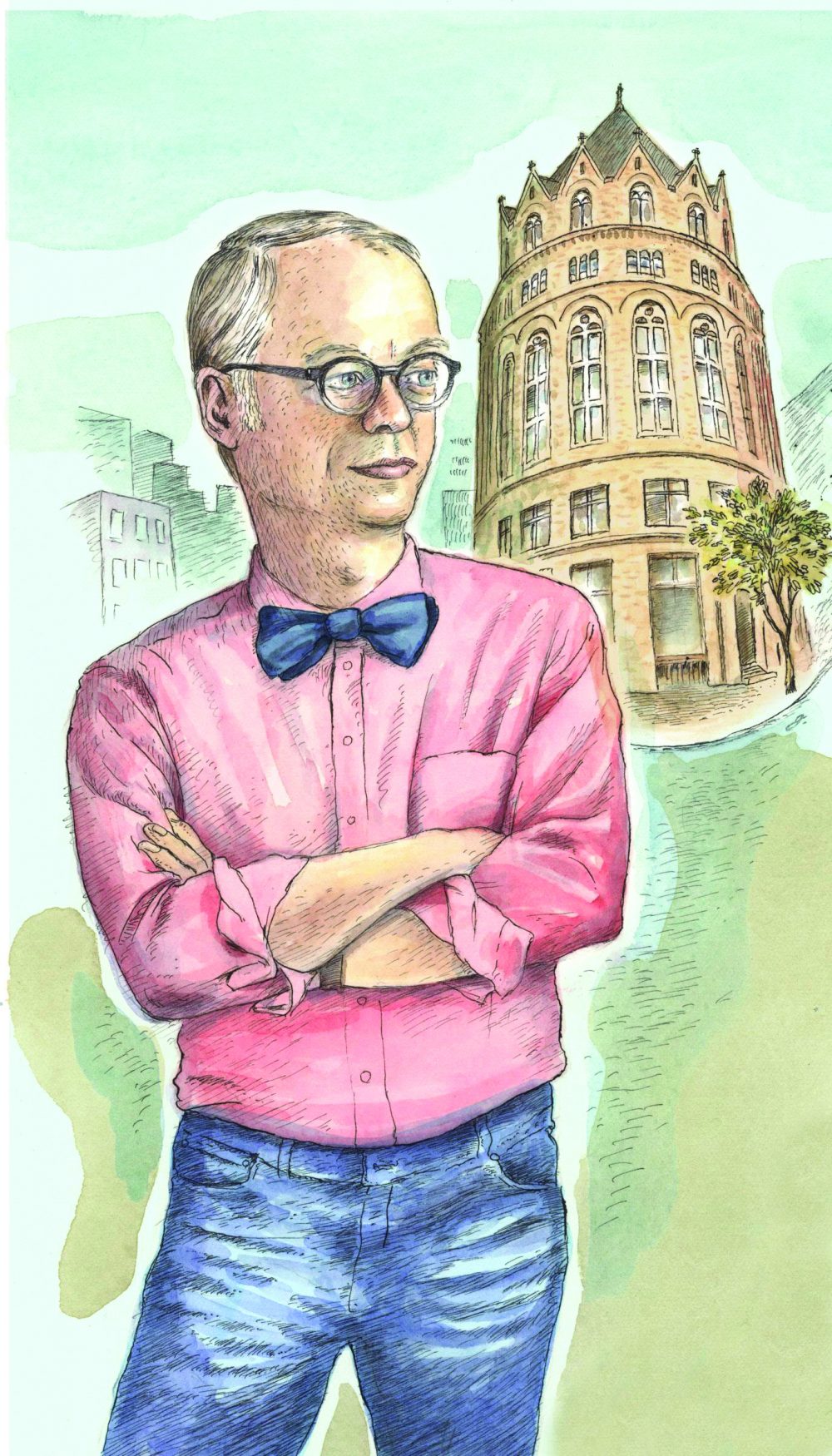

I had driven up from London to the Lake District to visit Ivan Day, who has lived most of his life in the world of the 17th century. He occupies a modest home on a narrow lane with a rambling English garden and a view of the town and pastures below. It is a picture postcard for the saying, “There will always be an England.”

Step inside and one is transported back to the Middle Ages, part museum and part working kitchen. The fireplace is stuffed with a coal tender, and in front there's an antique rotisserie powered by a clock-jack—a Rube Goldberg device that looks like the inner workings of a grandfather clock with weights, pulleys, a large black iron crank, plus a bell that rings when the jack needs winding. A massive mortar and pestle stands in the corner; the mortar is made of wood and stands 4 feet tall; the top of the pestle reaches over one’s head and is held in place with a bracket fastened to the wall. (The pestle is lifted and gravity does the rest.) The bric-a-brac cupboards hold extensively decorated sugar and gingerbread molds (3-foot high gingerbread royalty was sold by street vendors), plus a library of cookbooks dating back well before the 19th century.

On the menu was a leg of lamb cooked on the rotisserie, plus mashed potatoes, finished off under the dripping roast to acquire a rich mahogany crust. The potatoes were, arguably, the best thing I have ever eaten. It was a reminder that roasting was an art and that “roasting” meat in an oven, our modern version, in nothing more than an insipid, baked imitation.

Cooking began with fire and, in many parts of the world, the tradition continues. In Florence, at Trattoria Sostanza, one parts the beaded entrance to enjoy bistecca alla Fiorentina, steak grilled over a simple wood fire. In the Sahara, one finds small, flat ovens dotting the landscape, used by nomadic Berbers who have limited fuel to bake flatbreads. In Vietnam, street vendors in a small northern village cook on grates over wood, offering eggs hard-cooked in the shell and grilled yams. In Sichuan, a wok is an efficient cooking device, heating up quickly with a minimum of fuel. And in Argentina, whole spatchcocked lamb carcasses are placed on large metal racks, angled toward the wood fire at the center of a roasting circle.

Once the cooking pot was invented, cooks could boil water. Small animals or parts of large ones were easily cooked at the perfect temperature since water cannot rise above the boiling point. (Tthough abandoned by modernity, the French pot au feu and the Austrian Tafelspitz are reminders of this mostly lost art.) Then stomachs and intestines were stuffed with forcemeats and boiled alongside the bigger cuts. Cooks discovered steam and the English pudding was born, an economical way of cooking almost anything in a bowl—sweet or savory—with a minimum of fuel, just enough to keep a modest amount of water producing steam. (See our recipe for steamed marmalade pudding on page XXX.)

Traveling the world, one is reminded that our culinary beginnings were hardly primitive. They were clever and practical, perfectly suited to the climate, the fuel, the technology and the ingredients. Many cultures cooked flatbreads on hot stones (including Native Americans, who made an early version of hoe cakes), roasted pigs and other large animals underground on a bed of coals or heated stones, or used salt to quickly cure fish for ceviche, a simple lunch served on fishing boats off Peru, finished off with a squeeze of lime.

Years ago, I recreated a 12-course Fannie Farmer dinner and discovered the method in the madness of 19th century cookery. Though larding, multi-layer gelatins and brain balls may no longer be practical in the 21st century, the stock pot on the “back burner” is the perfect example of optimizing the tools at hand, a dumping ground for bits and pieces that eventually yield a rich stock.

The lesson for modern cooks is adaptability and a keen eye for culinary advantage. Our forebears shifted to gas from wood, to stovetop from fireplace, and to the skillet from the cooking pot. There is something new stirring in our culinary souls, something bold, fresh and simple. Now it is our turn to change.

And yet, I welcome tradition as a paean to the soul—a connection with the pageant of human history. Though I will tea-rub my turkey, jazz up the mashed potatoes with spices and horseradish, and serve ginger-spiced steamed marmalade pudding for dessert (along with apple and pecan pies, of course), these are still variations on tradition. That’s how I like it when the wind blows cold, the skies turn dark and leaden, and the fireplace springs back to life after summer hiatus. The past will always have a seat at my dinner table.