Your email address is required to begin the subscription process. We will use it for customer service and other communications from Milk Street. You can unsubscribe from receiving our emails at any time.

It Lives!

Back to September-October 2020

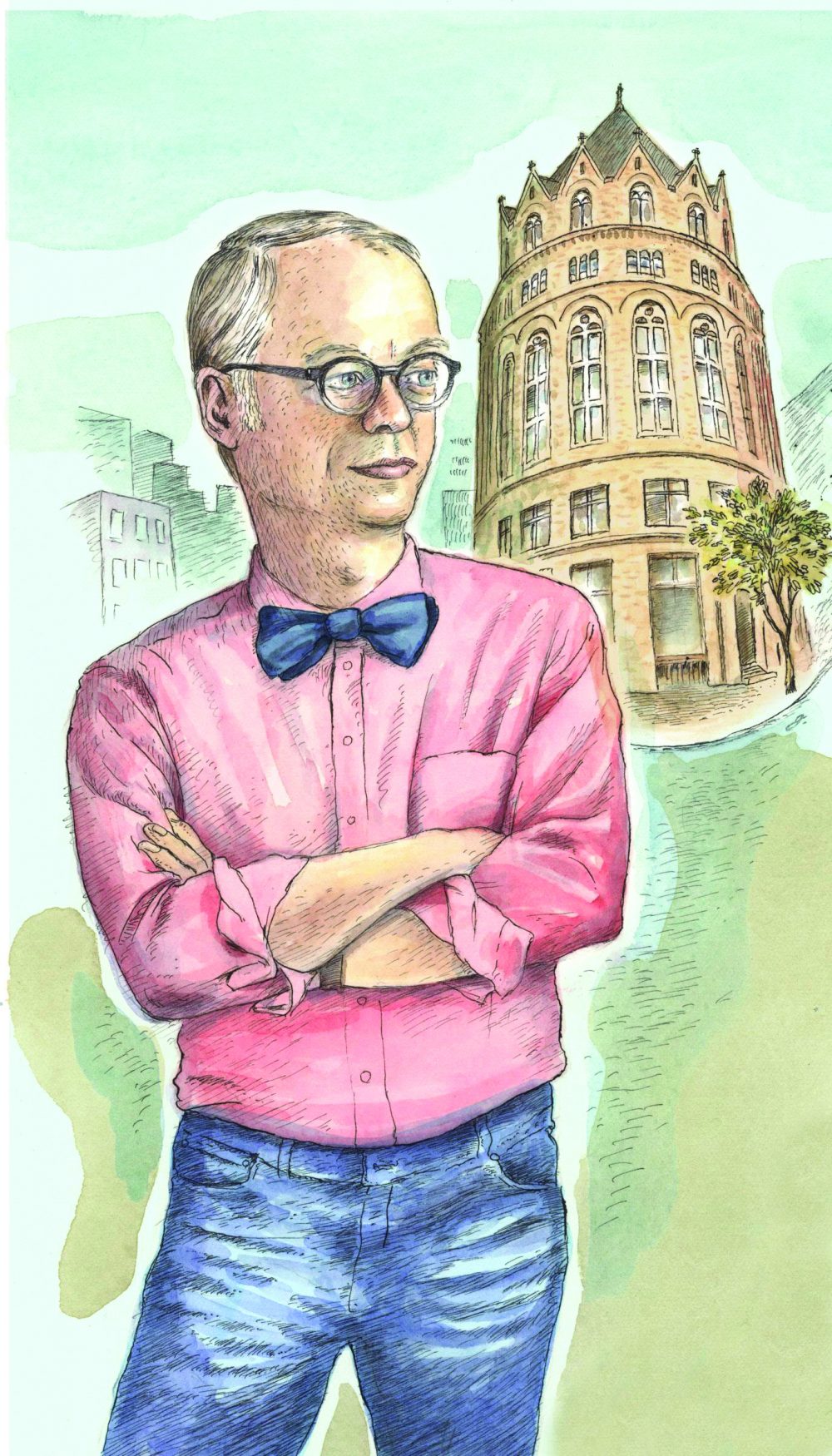

Karl De Smedt manages the world’s only sourdough library in Belgium, which contains over 120 rare and ancient starters, some dating back to the Klondike Gold Rush. They are fed bimonthly and De Smedt occasionally takes one home to bake a loaf.

My recent conversation with De Smedt reminded me of the mysteries of sourdough: flour, water and time produce leavened dough. This magical transformation is due to wild yeast spores, invisible single-cell organisms that cause flour to ferment in the presence of water. In the 19th century, doctors thought that cholera was caused by “miasma,” a form of noxious night air that carried disease. They were wrong—cholera is caused by contaminated water—but in the case of sourdough, there is indeed a “miasma” of yeast and we are deeply grateful for it.

Wild yeast is a curious thing. De Smedt analyzes the microbiological makeup of starters from around the world and has discovered, for example, that starters from Switzerland and Mexico share a wild yeast not present in any of his other samples. Both samples originated at high altitudes—is that the connection? Other sourdoughs share microorganisms that were found on the hands of the bakers which suggests an even more sci-fi possibility—when you bake bread, that loaf may be related to you.

Starter No. 100 is made from cooked sake rice, an old Samurai recipe; No. 72, a Mexican starter, has to be refreshed with eggs, lime and beer. Starters from different places have different flavor profiles. De Smedt goes as far as to describe starters as people. “A starter has its own heart, almost its own will. Treat a starter nice and it will reward you tremendously, like a good friend.”

But don’t start thinking that of your sourdough starter as a warm, fuzzy pet; it’s ruthless. As the lactic acid bacteria builds up, bacteria that cannot survive in an extreme acidic environment are killed off. Sourdough eventually becomes a simple, less diverse entity, one that obeys the Darwinian rules of nature.

Like other forms of life, sourdough starters also change as they age. If you start feeding a starter a different type of flour, it will change. If the temperature moves up or down by just a few degrees centigrade, it will change. (Colder temperatures promote the growth of stronger acids; warmer temperatures produce more milky lactic acids. That is why in northern regions, such as Scandinavia, the breads are more acidic than in southern Europe.)

Another surprise is that De Smedt feeds his sourdoughs only once every two months, not every few days. He feeds them three days in a row to preserve the balance and flavor of the acids in the starter, but he points out that you can let a starter sit refrigerated for up to a year, though it may lose some of its character.

Flatbreads are even simpler. There is saj, paratha, naan, the Uzbek flatbread known as non, k’sra from Morocco and pita, which can be made easily at home. Like magic, it puffs up while you watch. One of my favorite breads is ka’ak asfar, an Arab bread I tasted in Galilee; the name translates as “yellow bread.” It contains turmeric, nigella and sesame seeds, and mahleb, the seeds from cherry pits for flavoring. The small, sweet round loaves are a reminder that the possibilities are infinite.

All of this is to say that the cooking, at its simplest, is connected to some deeper mystery. The air is alive with possibilities. Flour and water, combined, fermented, shaped and baked in a thousand different ways, offers us a clue to the diversity of life on earth. Every type of wheat and every strain of wild yeast is different and every culture mixes, shapes, flavors and bakes their bread to their liking.

And bread has a memory. De Smedt says, “After all, more than distinct flavors, aromas and biochemical characteristics, what we keep in each of these jars is nothing less than history.” Every jar of sourdough tells a story, as does every loaf we bake at home. Something from almost nothing, shaped with our hands, baked from our past for our future.

September-October 2020