Your email address is required to begin the subscription process. We will use it for customer service and other communications from Milk Street. You can unsubscribe from receiving our emails at any time.

Welcome to Milk Street

Back to Charter Issue, Fall 2016

Charlie bentley used to say, “That’s the one we’ve been looking for,” referring to the last bale of hay slung up into the loft. It was celebrated with a black cherry soda from the machine at Carl Hess’ Texaco station.

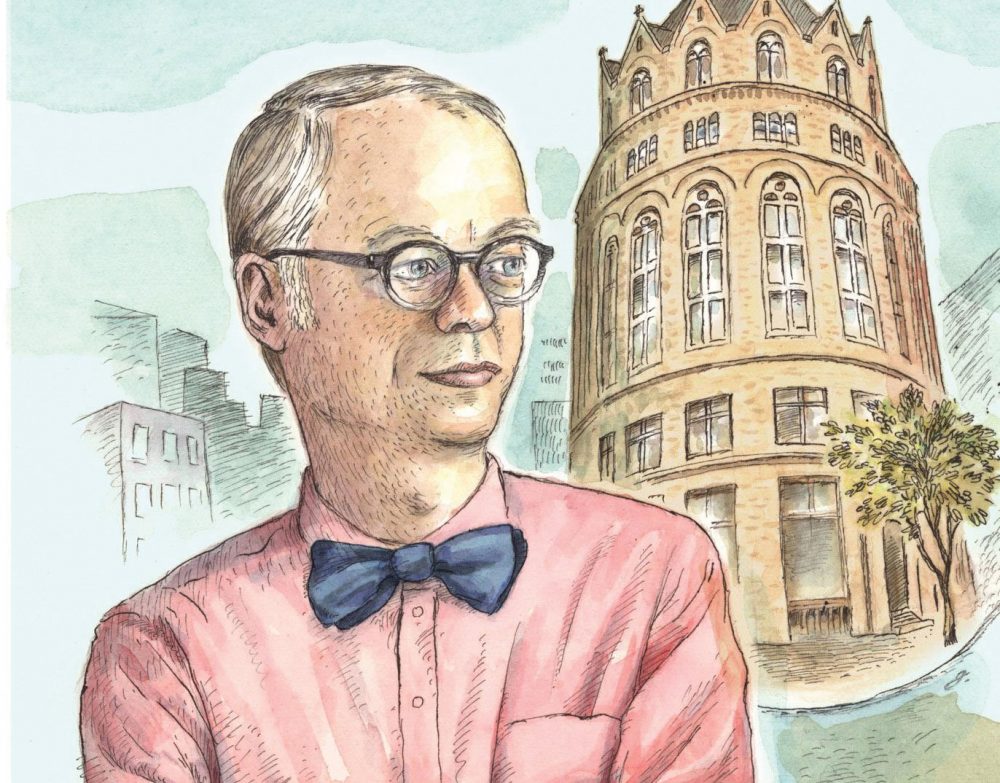

This charter issue of Milk Street Magazine also is “the one we’ve been looking for,” particularly if you’ve been looking for a new way to cook. Generally, I’m no fan of shortcuts or bold promises, so when someone offers to make cooking easier and better, my skeptical nature demands an explanation.

I’ve cooked the food of my New England childhood for over half a century, followed by all things French, a taste of Italian, as well as occasional forays into Mexican, Moroccan, Indian and Asian. My world was mostly northern European fare, a cuisine based on meat, heat, bread and root vegetables. It is a cuisine almost entirely devoid of spices, one that uses a limited palette of herbs, fermented sauces, chilies and strong ingredients, such as ginger. It is a cuisine based on technique, building flavors using classic cooking methods.

There is no “ethnic” cooking. It’s a myth. It’s just dinner or lunch served somewhere else in the world.

Ten years ago, I was driving into Hanoi from the airport. We overtook a sea of motorbikes, some with crates of pigs on the back, one with a middle-aged man balancing lumber on his shoulder, and several bearing whole families precariously perched, grasping hard and buffeted by the wind. It was a foreign shore.

Then I ate the food. Lemon grass with clams. Pho. A breakfast banh mi. Roadside stalls selling grilled foods like eggs in the shell and sweet potato. Mango and papaya. The salads. Hot, sweet, salty and bitter. Broth and noodles. Coffee with condensed milk and raw egg.

The realization dawned slowly. There is no “ethnic” cooking. It’s a myth. It’s just dinner or lunch served somewhere else in the world.

I’m from Vermont (at least my soul tells me so) and I have taken continuity of place and tradition as a tenet for the good life. The happiest among us, I’ve found, usually are from somewhere. It matters. But when it comes to food, let me propose new rules.

We think of recipes as belonging to a people and place; outsiders are interlopers. Milk Street offers the opposite—an invitation to the cooks of the world to sit at the same table.

A week later, in Saigon, I was picked up outside our hotel on a motorbike. Though I had driven a taxi in New York City, this 20-minute journey was heart-in-mouth. Intersections were vehicular Russian roulette, a game of chicken at every corner.

We made it to a ground-floor apartment where I was introduced to a local cooking teacher. She was patient and taught me to make a variety of dumplings in a kitchen that was little more than a table and two small propane burners. Slowly, I started to feel at home: the slicing, the shaping, the shared effort. I was the novice, and a cook halfway around the world was the expert.

I didn’t return home to cook authentic Vietnamese cuisine. I did, however, return a better cook. I learned to use a cleaver for slicing and not just chopping, to use meat as a flavoring, to think of herbs as greens and not just accents, and to appreciate salty, bitter and sweet in new combinations.

Milk Street is about that moment in that kitchen in that city and the thousands of other moments we will experience in the coming years. Ethnic food is dead; it smacks of the sin of colonialism. This is a culinary—not cultural—exchange. There are enduring kitchen values that travel easily from Saigon to Kiev to Jerusalem to Quito to London to New York.

I recently spoke with Naomi Duguid, author of “Taste of Persia.” In Armenia she was hiking through an apple orchard and was invited home by a local family. They lovingly prepared a single apple, slicing it neatly, arranging it on their best plate. And in the twilight, without a common language, Naomi ate the apple. And as she told me the story, she cried.

This is why Naomi travels and writes cookbooks. Cooking is not pedantic. It’s elusive, magical and alive with the poetry of life. And food is the common language. All food is everyone’s food.

Welcome to Milk Street.

Charter Issue, Fall 2016