Your email address is required to begin the subscription process. We will use it for customer service and other communications from Milk Street. You can unsubscribe from receiving our emails at any time.

Inyama! Inyama! Inyama!

Back to July-August 2017

It was a June night in 1969 under a stretched canvas of star- splattered sky in the Sahara, somewhere between Tamanrasset, Algeria and Agadez, Niger. I was driving the first of three Land Rovers that had been specially outfitted for the rainy season was about to begin in the lower Sahara, we had trouble getting permission to drive south, but an appeal to the State Department smoothed the way.

Around midnight—we did not drive during the heat of the day—we became lost. The “piste” (road) had ended two days back, but the piles of rocks that marked the way had also disappeared. I got out and stumbled about near an old well, the yellow light from my flashlight illuminating a half-dozen mummified camel carcasses. Bad water? We camped and waited for morning to regain the track toward Agadez. That evening, we made it through a sandstorm, rain and mud, with only a liter of gas among the three trucks.

For most of my life, my travels in Africa were just that, something reminiscent of Rudyard Kipling: dinner with Barbara Hutton at her Casbah palace in Tangier; a night spent in a small village in the Central African Republic in the midst of a funeral celebration; an arrest at machine gunpoint in the Congo; an afternoon sitting on old truck tires, sharing food with Mbuti pygmies in the Ituri rainforest.

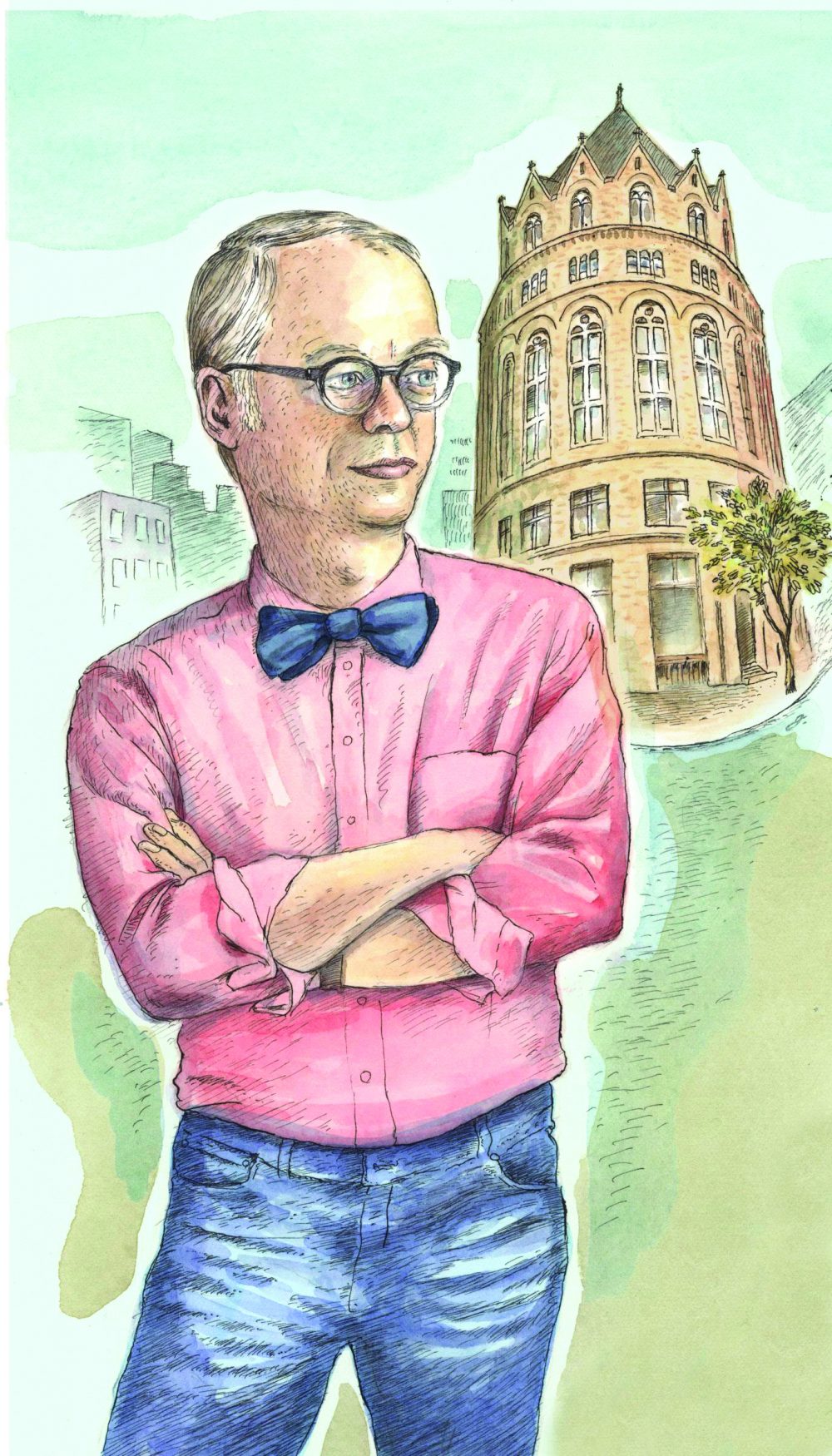

“Inyama! Inyama! Inyama!” (Meat! Meat! Meat!) Those were the sounds that greeted our editorial director, J.M. Hirsch, last month as he made his way through Mzoli’s Place in Gugulethu, one of the more turbulent townships of Cape Town (see page 11). Black, English, colored, Indian, Afrikaner and iterations in between showed up on a Sunday for braai, a South African style of barbecue. It was a seven-hour experience—waiting in line, ordering a bucket of raw meat, getting it cooked and sauced, then carrying it outside to eat (no utensils) and dance.

That’s the Africa poised to take on the culinary world. On an outdoor patio in Senegal, one hunkers down and shares a dish of thieboudienne. In Ghana, a cook makes jollof—a one-pot rice dish—or peanut butter stew. In Morocco, it’s a platter of tagine with ginger, saffron, olives, cumin and preserved lemon; a pastilla—phyllo filled with ground meat and cinnamon—or a stack of giant crepes served with jam and coffee on a rug in the desert.

The food is eaten by hand. It is eaten in a tent by the end of a small lake on the far side of the Atlas Mountains. It is eaten at small, roadside eateries with fly-specked walls and bathrooms so dark they feel abandoned. It is eaten at a makeshift table in the central square of Marrakesh, a plate of grilled lamb kofta with chili oil. It is eaten beside Berbers, Arabs and tourists under the light of naked bulbs, amidst a thousand skewers of meat and vegetables waiting to be fired.

Africa is desert and densely packed cities. It is jungle and savannah. Mountains and coastal plain. Across it all, there is something uniquely African when it comes to food. Perhaps it’s the hospitality or that food is utterly social. Nobody cooks alone.

Africa is, in part, a vast farmers market of old foods for a new world: red sorrel, grains of paradise, fermented cornmeal, pawpaw, true yam, cocoyam, bambara beans and kenkey. It claims dishes that are simple enough to travel anywhere, such as suya—strips of skewered meat grilled with a peanut coating. And West Africa is the root of much of our Southern food, from Carolina Gold rice, gumbo and okra to black-eyed peas, jambalaya and peanuts.

As the cradle of civilization, Africa offers culinary redemption, putting food back where it belongs: in the bosom of the family, among friends and neighbors, passed from one generation to the next. Food is not a lifestyle; it’s life.

One morning at a riad (small family hotel) in Fez, I awoke to the sunrise call to prayer and then a simple breakfast. A small cup of yogurt, a tiny glass of orange juice and harcha, a semolina flatbread baked in a tagine. We were eating on the roof—a dusky orange sky promised a hot day ahead. The portions were small but every bite was exquisite. The juice floral, the yogurt lively, the harcha tender. Strong, sweet mint tea followed.

On a rooftop in Fez or in the heart of Gugulethu, you can feel the rhythm, an ancient drumbeat that joins food and life.

July-August 2017