Your email address is required to begin the subscription process. We will use it for customer service and other communications from Milk Street. You can unsubscribe from receiving our emails at any time.

Welcome to Monteveglio!

Back to November - December 2022

Monteveglio is a small village on top of a mountain west of Bologna, Italy. With cobblestone streets and stone houses, it could easily double as a movie set. Remains of Roman villas date back to the 1st century, though the area has been inhabited since the Neolithic period. There are two main attractions: the church and our main destination, a small restaurant/hotel called Trattoria del Borgo. The church sits at the very top of the summit; a monk in classic Hollywood garb (brown robe, rope belt) was mowing the lawn, smiling to the occasional tourist but otherwise oblivious to their coming and going.

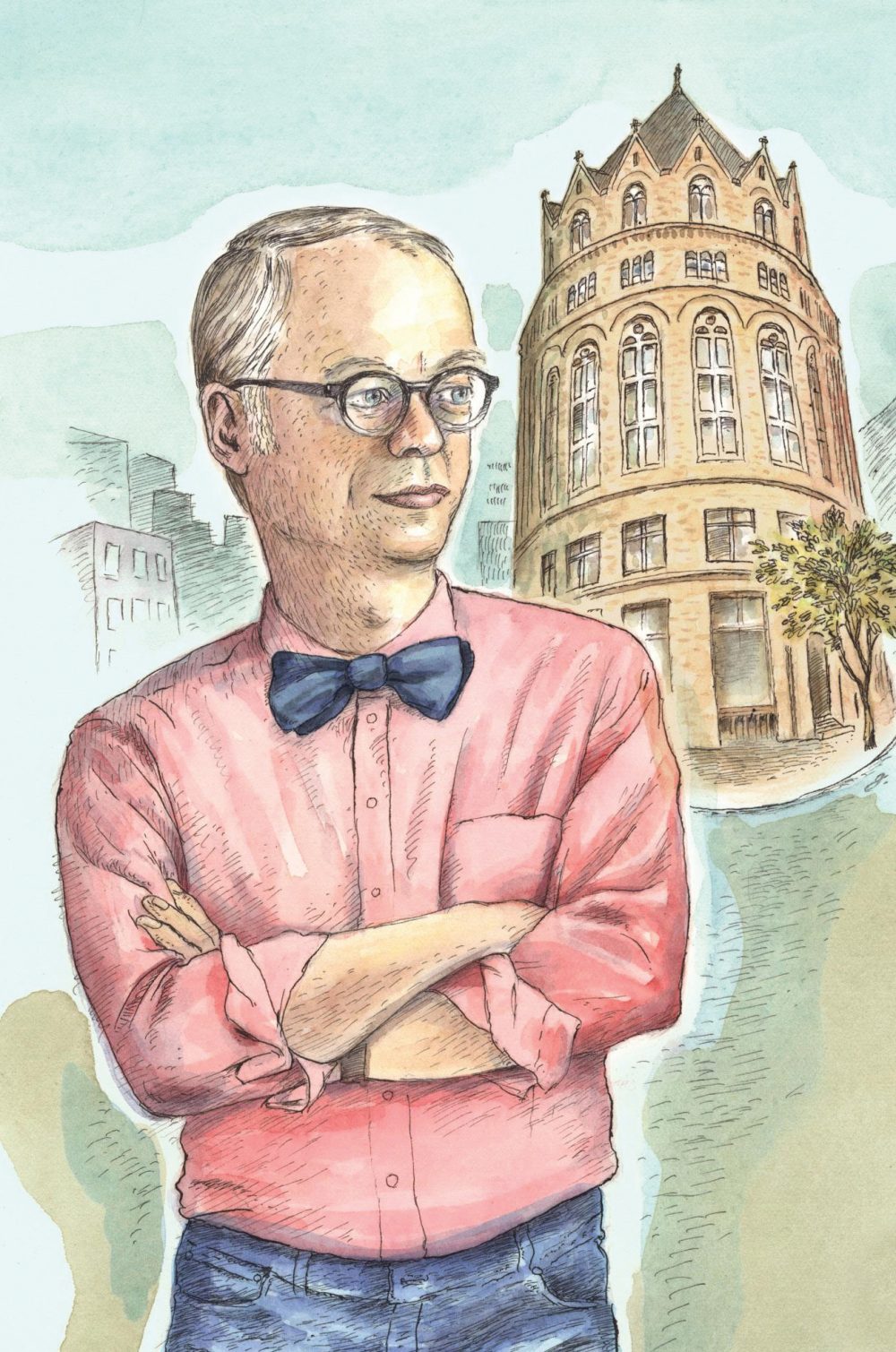

The owner, Paolo Parmeggiani, was thoroughly modern in the Italian style: affable, charming and the consummate host. On his stone patio overlooking the valley, he explained some of the culinary history of the region. After the wheat was harvested, fields would be burned and any remaining wheat berries would be gathered by the poor (hence the term, farina dei poveri). A related term, cucina povera, is an important concept in Italy. It combines a style of cooking that is authentic, local and from the land. Other common culinary terms are cucina espressa and cucina immediata, which also describe passatelli, the quick homemade pasta dish we were about to make, a mixture of breadcrumbs, eggs and grated cheese, passed through a potato ricer into boiling water and served with chicken broth.

Parmeggiani had three bowls prepared, one filled with breadcrumbs, one with eggs, and the other with finely grated Parmesan. (Parmigiano-Reggiano is made here in Emilia-Romagna, and so it works itself into almost every dish.) He mixed it by hand until he had a soft dough, which was placed into a metal potato ricer, extruded over boiling water, cut into short lengths with a knife, and cooked for a few minutes, like Spätzle. The only other ingredient besides salt was nutmeg, which, oddly enough, made all the difference, adding just enough interest to provide character. Passatelli is served in a bowl with chicken stock and, if you are in Emilia-Romagna in the fall, copious shavings of modestly priced white truffles. It was one of the best dishes of my life. Also the fastest.

Simplicity of preparation reflects the true essence of the culinary arts. It’s a lesson we’ve learned around the world. In Mexico City with chef and restaurateur Eduardo García, who cooked a pot of beans on a chinampa, one of the floating islands in the canals of southern Mexico City. A chili salsa was thrown together using the bottom of a beer glass as the pestle. And since we had no spoons, we used rolled-up blue corn tortillas. Thousands of miles traveled for a pot of beans. And it was worth every mile of the journey.

Other travels have taken us to northern Israel. We learned Palestinian cooking with Reem Kassis, author of “The Palestinian Table.” She invited us into her parents’ home for a feast of maqlubeh (a spiced rice and meat casserole with fried vegetables) with as many dishes as there were friends and relatives at the table. On a tour of the Galilee Valley, we also tasted maftool, an Arab pasta, similar to couscous, that was cooked with onions and chicken; ka’ak asfar, a sweet turmeric bread with ground nigella and sesame seeds; smeediyeh, fine bulgur mixed with caramelized onions and greens; hashweh, a mix of rice and meat with allspice, cinnamon and nutmeg; freekeh, smoked wheat berries, cracked and dried, often served as a pilaf; and a fragrant rose petal jam that her mother makes and serves over a simple cornstarch pudding.

It’s easy to divide food into countries and cultures—our food and their food—but this does a great injustice to the potential of cooking as common ground. Instead, pull up a chair at any table around the world, thank your god and your host, and enjoy the universal blessings of comity and hospitality.