Rintaro

By Sylvan Mishima Brackett

Sylvan Mishima Brackett moved to California from Japan when he was just 1 year old. Living in a house that his father built, he grew up with kerosene for light, wood for heat and a garden that supplied most of what they ate. So it makes sense that his name in Japanese, Rintaro, means “boy of the woods.” Fast-forward and Brackett found himself working for Alice Waters at Chez Panisse and then opening Rintaro, where he serves food “that you’d expect if the Bay Area was a region of Japan.” Yes, this cookbook provides lots of serious Japanese recipes and delves into the mysteries of making, say, dashi (which includes smearing bonito with a paste made from the meat from between the bones). But what I most loved were the takeaways and the recipes that will impact my midweek repertoire. Salt salmon and let it dry out in the fridge overnight (this firms up the meat and gets rid of the fishy smell when cooking), cucumber sunomono (vinegared cucumber), a yakitori grilling sauce, chicken meatballs, and frying breaded chicken breasts (sliced thinly) with a bit of cheese in the middle, the perfect recipe for my persnickety 6- and 4-year-olds. I was also intrigued by the notion of seasonal sake, his suggestion of frying outside rather than inside and how Japanese chefs transform French desserts with flourishes such as mochi-wrapped strawberries. The book itself is fully illustrated, but the fabulous woodcuts really set it apart—like Japanese cooking, this book is a work of art.

Buy on Amazon

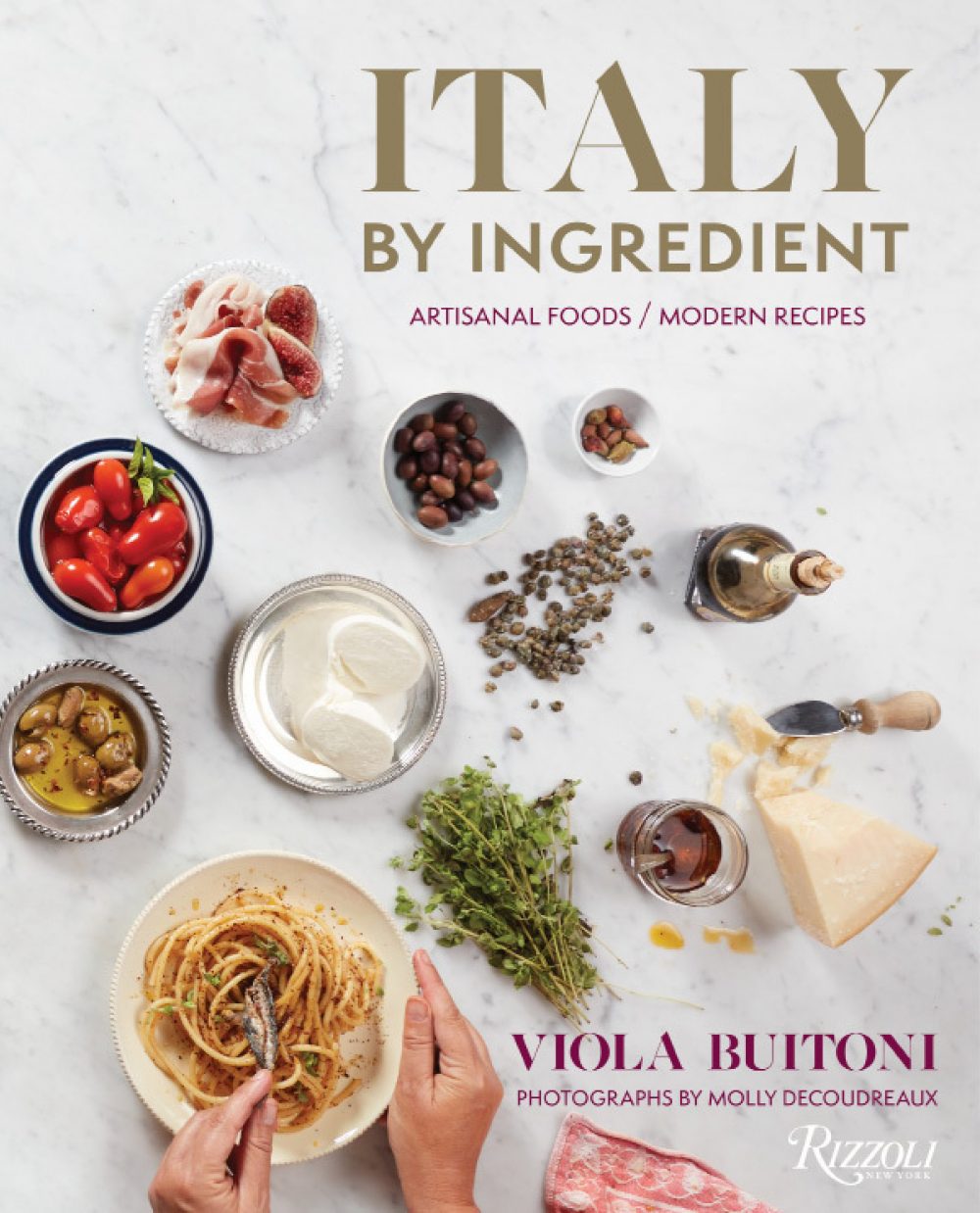

Italy by Ingredient

By Viola Buitoni

On a recent trip to Umbria, I spent time with Viola Buitoni, who gave me cooking lessons and acted as my guide, introducing me to dishes and cooks way beyond my Italian experience. Buitoni is a sixth-generation Italian and grew up in a former convent in the midst of an olive grove. (Talk about perfect casting.) What I love about “Italy by Ingredient” is that it gets at how Italians really cook, offering not a touristy, cream-laden fettuccine Alfredo but real everyday dishes: pasta with zucchini and shredded ricotta salata; baked custard with a balsamic vinegar reduction; and cold summer rice with tomatoes and basil. The appeal of Italian cooking is “ingredients married to simplicity.” Italians make salad with bread and tomatoes (panzanella), they are perfectly happy with a quick, simple tomato sauce, they think pasta dishes are first and foremost about the pasta, and a trip to the local butcher shop for guanciale can lead to a hundred different dishes. If you want to get a peek behind the curtains of Italian cooking, this is a great place to start.

Buy on Amazon

Flavorama: A Guide to Unlocking the Science and Art of Flavor

By Arielle Johnson

OK, by now, we all understand that most flavor is derived from aroma, not the five basic tastes on your palate. Aroma starts with airborne molecules entering your nasal cavity and then up to the olfactory epithelium, a sticky carpet of densely packed smell receptors. The brain must make sense of all this, even though this region of the brain is also responsible for conscious thought, language, emotions and subconscious memory. (Hence the power of aromas to call forth memories.) A good example of the difference between taste and smell is lemon juice: Add it to a simmering sauce, and it will taste flat. That is because the aromas have dissipated, leaving one with just the taste on the palate, not the powerful aroma. And with 40 billion “smellable” molecules, things get complicated quickly. At the end of the day, it is the brain that does the tasting, since aroma molecules have to be interpreted based on experience and memory—the more you taste, the better you get. In “Flavorama,” Arielle Johnson also offers many cooking tips, but this is my favorite: Be frugal with salt at the outset of cooking if a liquid is being reduced—evaporation will turn your dish too salty.