Your email address is required to begin the subscription process. We will use it for customer service and other communications from Milk Street. You can unsubscribe from receiving our emails at any time.

September 14, 2023

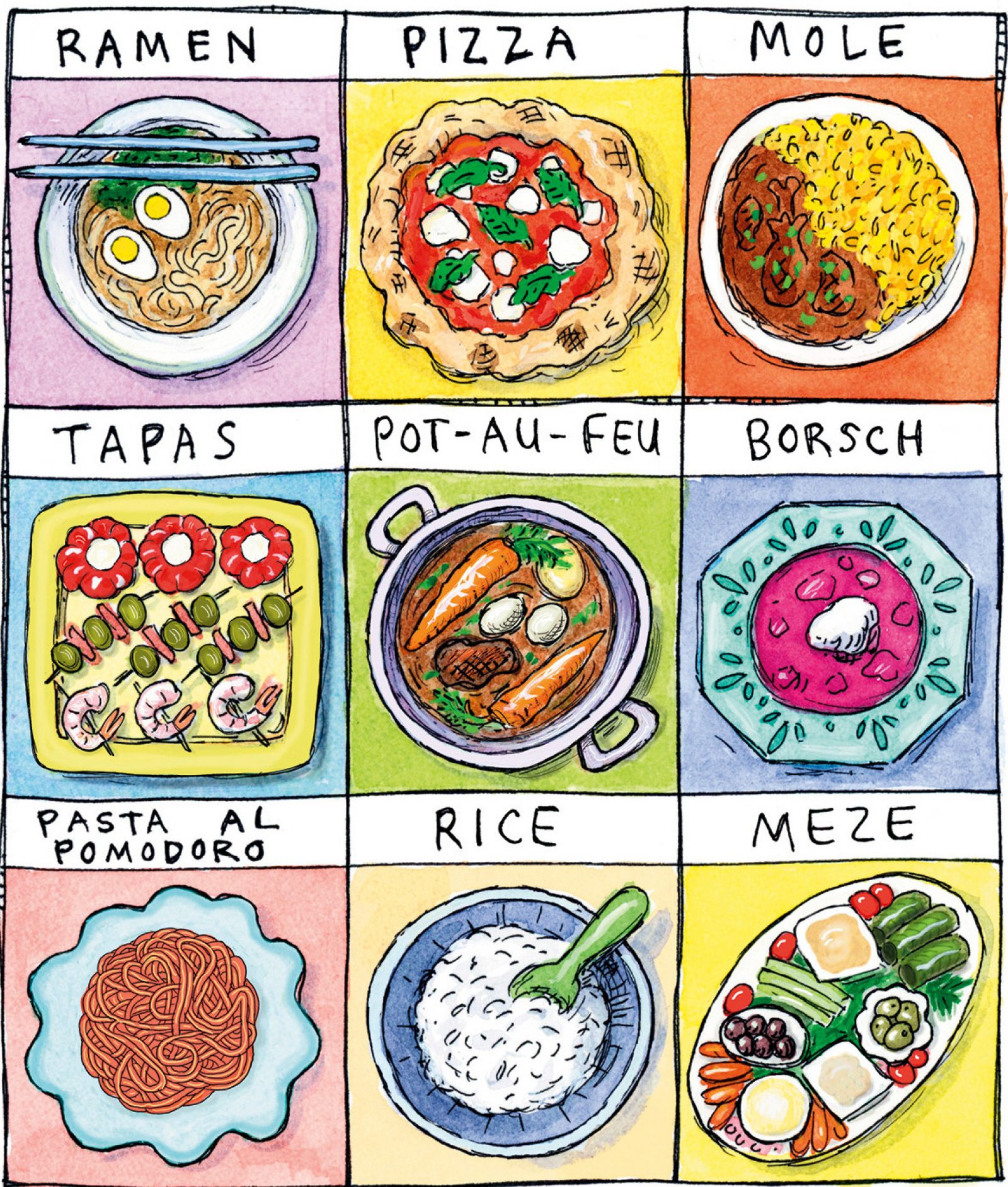

Is Pad Thai for Real? Investigating The Truth About National Dishes

Did you know that pad Thai was invented less than a hundred years ago? And that pizza became popular across Italy only after it was embraced in the United States? This week, we’re joined by author Anya von Bremzen to discuss the unlikely origins of some of the world’s most famous national dishes, from pot-au-feu in France to borscht in Ukraine. Plus, we crack the case on wine fraud with journalist Rebecca Gibb; Dan Pashman de-influences school lunch; and we prepare Thai Salad Rolls.

Questions in this episode:

"Heirloom beans are really expensive. Are they worth the cost?"

"Can you help me recreate a mint-infused oil I ate in Mexico?"

"What's a good recipe for silkie black chicken?"

"Why do some restaurants leave the tails on their shrimp?"

Christopher Kimball: This is Milk Street Radio from PRX. I'm your host Christopher Kimball. Chances are when you think of Italy, you will of course, think of pizza. But to understand how that came to be, you have to understand a phenomenon called the pizza effect.

Anya Von Bremzen: It's a term that was coined by a Hindu scholar to describe yoga. Because yoga in India was no big thing. And then it became really popular abroad. And then it came back to India as something you know, which was to be now revalorized and respected and the same thing happens with pizza.

CK: Later on in the show, we're tracing the origins of the world's most popular national dishes. But now look at some of the biggest cases of wine fraud, starting first with Bordeaux in 1973, when winemakers were accused of adulterating at least 3 million bottles of wine, a newscast from the Associated Press labeled the scandal as winegate.

News reporter: Some of the most prominent and respected firms in Bordeaux have made illegal profits amounting to more than a million pounds. The House of Cruz founded 160 years ago, is one of 11 companies alleged to abducted cheap table wines with chemicals to change that taste, color and smell and the switching labels on bottles of red Bordeaux.

CK: We're joined now by author Rebecca Gibb to share the long history of wine fraud over the last 3000 years. Her book is called Vintage Crime. Rebecca, welcome to Milk Street.

RG: Thank you for having me.

CK: We're talking about wine fraud. And you say there are two types. There's when someone is putting an additive into the bottle, ostensibly to make wine tastes better. And then there's people who sell inexpensive wines with labels that look like it's it's rather an expensive bottle. But let's take the first case, and this is something you write about in Vintage Crime. You say it would take chemists two millennia to come to grips with the science of turning grape juice into wine. And of course, how to prevent it from souring. In other words, sour wine was very common until fairly recently, is that the main reason people were adding things to it to make it taste better.

RG: Throughout history, wine has been sour. And basically, oxygen has been wines enemy for time and immemorial. People didn't know how wine was was made. It was some sort of mystical process almost even until sort of the mid 19th century, it really didn't taste very nice. So yeah, people will be adding stuff to make it taste sweeter. In Roman times, for example, always using herbs or even seawater, or in case of sort of 17th century Germany lead acetate, which caused people to keel over.

CK: So, the other things I found this fascinating that they might add pepper, mastic, which is that sap from a tree, saffron, mushed up fruits like dates. And the interesting thing here is that over a long period of time, many people actually preferred adulterated wines. They got used to the flavor, but it wasn't viewed as a bad thing. I think before we move on, let's I think it's an important point that people understood wines were adulterated for a long time and they actually liked him that way, right?

RG: For sure, you know, you look at burgundy hoped she would make some of the most coveted wines sell for 1000s of pounds bottle. In 1930s, burgundy, the red wines from there were really weedy, quite thin, insipid, pale. They weren't a lot of fun to drink, to be honest. So, if you found some wine from warm Algeria that was deep in color and rich and flavor, you brought it up on a train to Burgundy and then you blended it with your thin and sour Pinot Noir. It made the wine a lot more lovely. So actually, people preferred the adulterated version in a number of instances.

CK: Yeah, and this adulteration, still continues well into the 20th century, maybe even today. You mentioned the 1980s, there were Austrian winemakers who put dye ethylene glycol, which is not something you really want to be drinking, to plump out their wines, methanol to increase the alcohol level. So, this is not an historic discussion. Adding chemicals to wine is something that was still continuing well into the 20th century, right.

RG: Yeah, for sure. I mean, you see that the methanol scandal in Italy people went blind killed some people. You see the dye ethylene glycol scandal, which was some people are incorrectly termed the antifreeze scandal. In the 1980s, it was still difficult for people to make a living out of wine. So, they were using methods to improve their wines to make them more lovely. The problem is, you're no longer using a natural product, you’re no longer using wine in these instances, and it's actually harmful to health and this is when the law actually acts.

CK: So okay, now now let's move on to I think the more curious part, and this is when people are actually selling bottles of wine for big dollars, like six figures. So, I know some people manufacture labels and they actually fill old bottles with new wine, of course, sell it for a lot more than it's actually worth.

RG: Well, that's what Rudy Kurniawan did in the 2000s when he was taking old bottles that had been used in New York restaurants. He was getting bottles sent over to him in his home in Arcadia, California. And he was refilling them. He was refilling them with some really, really excellent wines like these are not shabby wines that he's putting in them. They're absolutely top-class wines. He has a recipe book how to make whether it's, you know, pet ruse or___ he has these recipes. And He's fooling people. He is selling them at auction. He has labels, he has stamps, and then he's really slips up in 2008. When he sells some wine from Domaine Ponsot which is in Burgundy. He sells some wine from the 1929 Vintage. And he's he hasn't done very well here because Domaine Ponsot wasn't bottling in his own wines in 1929. So, Laurent Ponsot flies over to New York, he flies and says, hang on a minute, this isn't right, because we didn't make this wine. Anyway, it's quickly withdrawn from the sale. But it's from then on, people are starting watching out for what he's doing the FBI are on his case, in 2012, they raided his house. And the FBI agent says it's basically a white factory in this house. It was temperature controlled; it was freezing cold in this house. He was trying to preserve his wines, there was wine on treadmills, but he is the first person in the US to actually be prosecuted and sent to prison for wine fraud.

CK: So, let's assume you're a wine detective. Now, you can't open the bottle. So how do you figure out how does one figure out what their bottles legitimate or not?

RG: It's very difficult. There are people who do this for a living, and they look at the fonts and the label was the glass, right? Was it made in this yard? Does he have the right spelling on the bottle? Every you'd laugh, but it's quite common. There are other ways to find out you can do it scientifically, there are ways to do it with carbon dating, and there are nuclear scientists who have tried to detect whether your wind is from the period before there was nuclear material in the atmosphere or not. But really, you can't pinpoint it to a specific vintage, if it's sort of earlier than the 1960s and 1950s.

CK: Last question is, is there wine fraud when you get down to a 20 or $30? bottle of wine? What's your answer to that?

RG: Yes, but who cares?

CK: Okay, that's well, that's that's the answer I was looking for because I was thinking wine fraud would be, you know, for the really expensive stuff. But you just confirmed what I was told that even a $20 bottle of wine could definitely be fraudulent. Because someone put in $5 wine into the bottle and is making a $15 profit

RG: As long as it's not harmful to health I think that at the very low-price points, people just want a good drink. And there are so many laws that are intended to prevent wine fraud, that the consumer should feel relatively safe.

CK: And a slight thrill that it might be fraudulent anyway.

RG: I think that you'll find that I would hope that 99% of wines that we see on our shelves are absolutely what they ought to be and what they say they are. There's very little reason today for people to commit wine fraud at the lower price points. People can make good wine and they can bottle it. We know how to ripen grapes. We know how to harvest them. We know how to protect them from souring. We've got glass bottles, we've got corks, we've got screwcaps Your wine should get to you in the way that the winemaker intended, and no one should have to lie.

CK: Rebecca, it's been a pleasure. I feel a little nervous about wine but not too much. Thank you.

RG: Thank you.

CK: That was Rebecca Gibb, author of Vintage Crime, a Short History of Wine Fraud, which will be published next month. Now it's time to answer your cooking questions with my co-host, Sara Moulton. Sarah is of course the star of Sara's Weeknight Meals on public television, also author of Home Cooking 101. So, we both been around a bit in the last year did you come across something that was surprising, new, different change to technique made you think about food differently?

Sara Moulton: Sure. It wasn't anything that huge, you know, or earth shattering but we went to my nephew's house for dinner, and he made chicken thighs, and he got bone on skin on and he took the bone out, I was very impressed. He's very good cook. And then he cooked the chicken skin side down until they got very crispy. You know, I didn't pay enough attention because then he made some amazing sauce with reduced juices in this and that was pretty French. But what he did in the end is he put the chicken skin side up under the broiler at the end. And what struck me the most and it was so fantastic. was how ridiculously crispy these thighs were, you know, the sauce was fantastic. But even without the sauce. And I didn't realize the chicken thighs with the skin on could be that crispy. It's almost like they were deep fried, but without the frying. And so now I've been trying to do that. With some success. I don't think I've spent enough time I have to call him up against exactly what he did. And we know that chicken thighs don't dry out because they're higher fat content than white meat and far more forgiving. So, it's a good quick weeknight meal. Even if you don't put a fancy sauce on it because they just taste so good.

CK: Well chicken thighs can be cooked for a week you almost can't overcook them. I know it's great. I know when a broiler I have to say that's interesting. Yeah, the broiler is actually underused.

SM: It is but you'll also as we both know you can lose something in three seconds if you don't pay attention.

CK: I was in Paris recently. I went to a small Vietnamese place where he did chicken wings. Oh, I love chicken wings) and he basically put fish sauce and lime juice on and a little sugar. They were just absolutely Oh yeah, I don't even like chicken wings.

SM: Oh, I adore chicken well without the crisp factor lime juice, sugar fish sauce. Anyway, time to take a call. Welcome to Milk Street who's calling?

Caller: Hi, this is Chris calling from Hudson, Massachusetts.

SM: Hi, Chris. How can we help you today?

Caller: I have a question. Just a general one about heirloom beans. I guess my general question was whether you guys think they are worth it. Sometimes heirloom beans, I feel like can run you almost as much as a good cut of meat.

SM: Well, let me cut to the chase and say yes, I think they're so worth it. The thing about the beans you buy in the supermarket yes, they are much lower price. But you don't know how old they are. You don't know how fresh they are. And it makes a big difference in how they cook and what their texture is. And the thing about these heirloom beans is they're generally fresher, they generally have more flavor, and they generally have a more interesting texture as long as you cook them properly. I think it's worth it. Anyway, let's see, Chris, what do you think?

CK: Well, the term heirloom bothers me. Because there were a lot of heirloom apples that absolutely deserve to die off. Because they had horrible skins, or they were sour. Just because something's heirloom doesn't make it any good. Right? I would say overall, some of those are great, but you know, you'll find some of those beans you'll like and some you don't just because its heirloom doesn't mean you're going to like it. Some of the small red beans, you know, are great. I got some beans that were similar to ones I had in Mexico, sort of a cranberry being or a Pinto style bean. And those are delicious. But you know, you can get Goya beans in the supermarket too. And those sometimes are fine. So, I think the fresher the better yes. But you don't know. Here's what I would do. Try a few varieties and find a couple you really like and then it's worth the money. But it just depends on which bean and whether you like it or not. It also depends how you cook them and how you flavor them. Sometimes the other flavors, you're not really going to taste the beans that much anyway. But yes, in this case, I would say it's worth pursuing and you know, it isn't that much more money given how much you get out of it a pound beans, right?

Caller: Yeah, no, that's really helpful. I think one of the things that I was sort of stuck on is that heirloom seems to be the catch all for commodity beans in particular.

CK: Well, if it makes you feel better my kids call me heirloom.

SM: You are, I'd say vintage. Extra.

CK: Heirloom doesn't necessarily mean it's good.

Caller: Yeah, I'm looking for like some sort of things that can stand up on their own with like some garlic, some oil. Some onions is sort of my platonic ideal. Well, thank you guys so much. I really appreciate it. I'm big fans of the show. And this was a delight to talk to you.

CK: Yeah. Thank you, our pleasure.

Caller: All right, take care

SM: Thanks, Chris.

CK: This is Milk Street Radio. If you're struggling with a recipe, give me a call anytime. 855-426-9843. That's 855-426-9843. Or simply email us at questions at Milk Street Radio.com.

SM: Welcome to Milk Street who is calling?

Caller: Hi, there. This is Grace.

SM: Hi, Grace. Where are you calling from?

Caller: I'm calling from Dallas, Texas.

SM: How nice. How can we help you?

Caller: Okay, so my husband and I went to a restaurant in Mexico. And with the bread that they brought to the dinner table, they brought this oil, it was a mint oil, that clear green oil. It was so delicious. And I came home, and my garden is full of spearmint right now. And I thought, oh, I need to make some mint oil. Ideally, I'd like to make a bunch of bottles now and jar it or can it or save it for Christmas presents. I Googled how to make mint oil. And there's just many different methods. So, I'm just not sure about which method to use. And then once I do make it how long can I keep it?

SM: Well, let me ask you about the one you had in Mexico. Was there anything in there any kind of acid or anything besides

Caller: No, just pure green clear.

SM: Okay, here's the problem with mint or garlic or anything that's not naturally acidic. If you put them in oil, you're setting up an anaerobic environment, which is conducive to botulism. In terms of making this for Christmas, I would go the route of mint vinegar, not mint oil. If you want to make it for fun for yourself for a dinner the next day or two, here's what I would do, I would, here's a little rhyme brews infuse strain and use, you can throw the stuff into a blender. However, I have read, and Chris is probably going to weigh in on this one that if you use olive oil in a blender and blend for too long, you can get some off taste. So, if you do do it in a blender, do it quickly like whiz it and turn it off and then strain. And this would be one of the times where you'd want to bruise the herb to get the most out of it. That would be my best suggestion unless you want to get involved with acid, adding that to the oil. And you'd have to get the right percentage if you want it to last more than a couple of days. But let's see what Chris has to say.

CK: This is the point of the show, I ask you if you're feeling lucky, because you really I mean, things like garlic and oil, those kinds of things are really sort of dangerous. So, I would throw it in a blender or a small food processor, sort of like you're making a pesto except there's a lot more oil briefly whiz it till it breaks up. I might even be inclined to warm the oil and like not too much but warm it and let it sit for like 10 minutes with the mint in it to really infuse it and then strain it out with cheesecloth or whatever. And that would probably give you a green oil would give you a lot of flavor, but I don't think you want to have that sitting around too long. you really want acidic environment to stop all those bacteria from multiplying so I don't know how they did it. They probably made it fresh every couple of days.

SM: but Chris, what do you think about mint vinegar, which would be yummy? Yeah. What other suggestions would you have?

CK: Mint julips, ____

SM: Let's just go the alcoholic route. Let's go right there.

CK: Lime juice, Mint, sugar, rum. That's the solution to your mint problem.

SM: Yum Oh, are the other thing you could do, which would last a little longer is make a mint flavored sugar syrup. (Yeah, that's a good idea.) And then you'd have that for all those yummy things that Chris just suggested. And you could add more mint to your cocktails to you know, finish it off too.

Caller: Okay, okay good.

CK: All roads lead back to cocktails.

SM: Yeah, they do. I think so.

Caller: I wasn't aware of the danger of making oil. That's good to know.

SM: It's very real. You know, I'm sure there are recipes for making herb oils that last but it probably involves some sort of acid

CK: Well, there are lots of really good preservation books out there now or just go online and you might check out Serious Eats or someplace like that. And they probably have done tests on this so check them out. Yes. Thank you for calling.

Caller: Yes. Thank you so much.

SM: Take care.

CK: This is Milk Street Radio coming up the secrets behind national dishes. That's right up after the break. This is Milk Street Radio. I'm your host, Christopher Kimball. Pizza is to Italy as Pad Thai is to Thailand. But if you think that's always been the case, well, you're probably wrong. Author Anya Von Bremzen travelled across continents to learn the origins of the world's most famous national dishes. Anya, welcome to Milk Street.

Anya Von Bremzen: Thank you, Chris. Great to be with you.

CK: So, we're here to talk about your book national dish, and just how complicated it is to have one dish represent an entire country's history, and also its culture. So, there's a whole lot going on in these decisions, right?

AB: Well, to start with, it is a powerful idea as the idea of a nation. We kind of just assumed that nations always existed, that they always had national dishes and cuisines. But if you look at early 19th century, you know, there is no Italy there is no Germany, there are no nations, as we know them today, the nation state itself is a very young idea. And the idea that a nation is represented by a cuisine, or a dish is something that evolved and in sometimes in ways that were controversial, and not always organic. Look at pot au feu, which is what I look at in France, it has all kinds of regional variations and regional names. And the French were very successful at making the regional into something national into celebrating this diversity. Because, you know, for any kind of centralized government, the idea of unity and diversity, as a national slogan is really important to bring all these populations together.

CK: You talk about France, where until the revolution, it was a complete mishmash of different languages and cultures, you say people say, oh, the French people always spoke French. And then you're right, no, even at the end of the 19th century, they spoke regional dialects. So, we think about French cooking is being pretty straightforward, Karem, Escoffier et cetera, et cetera. But in fact, it's much more complicated.

AB: Yeah, far more complicated. But I start the journey in France because France was the first country that sort of consciously codified as cuisine, exported it in starting in the 19th century, as a uniquely French product that they could be proud of no other country has anything like this, the sauces, the terminology, as well as the restaurant. I mean, think about it. The restaurant as we know, it didn't exist until it was born in France, a couple of decades before the French Revolution.

CK: You talk about Oaxaca, and I was there a few years ago, and I was struck by the fact that my first day there, I had lunch with someone who explained, they were like, 16 different languages within half an hour of Oaxaca. And so, you know, a yellow mole outside of Oaxaca might be cornmeal in a stock with lamb neck in it, right? Whereas in Oaxaca, yellow mole might mean something totally different. But the fact the matter is, it was extraordinarily diverse. People didn't even speak the same language within an hour's drive.

AB: Oh, absolutely even Zapotec, which is a dominant indigenous language has something like 200 variations, and especially it varies from coast to the highlands. And when even we talk about something, so Oaxacan as mole negro, the black mole, every region has its own variation. One for instance, I forget which version it is. It has animal crackers, believe it or not as a thickener. Yeah. So, what are we talking about when we're talking about national cuisine? And yet, it's still a very powerful concept. And Oaxacan’s of all stripes still consider themselves Mexicans, but in different ways. What is it to be Mexican means different to different people.

CK: So, let's take some more specific examples. So, Pad Thai, sort of became the national food back in the 1930s. Do you want to tell that story and and how it actually came from somewhere else?

AB: Yeah, but I just like ramen is a a noodle dish that Chinese street vendors made in Thailand, which was then called ___ and then this dictator called Phibun, he essentially decreed it as a Thai national dish. So, while the Chinese vendors were being pushed off the street, and replace with dye vendors, they were getting this top-down decree essentially, that everyone should be making this dish, a Chinese noodle dish diversified with palm sugar and tamarind and other Thai ingredients. And then you had this intense promotion by tourism boards to promote it outside Thailand. And it's so interesting, I speak to so many Thai chefs who are trying to do quote, unquote, authentic regional food, which is now easier to find in New York. And they all complain how, you know, they came here, and they had to sling Pad Thai it's really interesting. It's considered like this kind of thing for tourists.

CK: So, I do want to ask you about authenticity, you know, my feeling is that it's a very difficult word to define and use. Because in the Middle East, for example, humus, you know, is made differently, not just in every town, but in every household. And the same is true for many, many other dishes. So why do we keep pursuing this idea of authenticity? You know, what does it really mean, especially in the modern world, where people move around, where cultures, there's mashups, and people have their own ideas of what makes the perfect recipe.

AB: Somewhere in the book, I kind of sigh and I reflect, oh, authenticity is such a powerful and monster marketing tool. (right) This is how places get branded. And marketed. This is how dishes get branded and marketed. Anything we should be aware of authenticity being a construct, I mean, what is authentic, to whom, and when. And that's the point I make over and over in the book, especially starting with kind of the neoliberal era defined by you know, the idea of economic competition, identities became brands, the idea of something being authentic became a brand. So, Korea put a lot of money into marketing their kimchi as their national product, and pizza to Neapolitans became something that they perceived it was being taken away from them with this intense globalization of pizza. So, in the 90s, you start having all these organizations to protect the origins, to protect the integrity of the product to protect the ingredients to make sure that it stays, you know, as part of your soft power as opposed to being just like this endlessly globalized product.

CK: You make the point like its basically flatbread guys, and it was it was cheap street food. So, is, is that your starting point for pizza?

AB: Pizza is a really intensely Neapolitan dish. So much so that at the end of the 19th century, even even in the beginning of the 20th century, it wasn't known. Not only that it was denigrated by northerners, for instance, Carlo Collodi, the creator of Pinocchio, he wrote a travel book for Italian schoolchildren as part of the process of unifying Italy. And he says, should I tell you what pizza is, it's something that resembles complicated filth. And then what happens is, there begins one of the largest recorded of migrations in world history of Italians leaving Italy and going to the Americas. And this dish of the Neapolitan poor, becomes accepted in the Americas becomes popular probably before it even happens back in Italy, on a national, any kind of national level. And then I talk about something called the pizza effect. And it's a term that was coined by a Hindu scholar to describe yoga, because yoga in India was no big thing. And then it became really popular abroad. And then it came back to India as something you know, which was to be now, revalorized and respected and the same thing happens with pizza. I mean, pizza doesn't become an Italian national dish until way into into the 20th century, even though we think it was always Italian.

CK: And you also say in Spain because they obviously celebrate hams, that that had a cultural subtext to it, right?

AB: Yes, the gammon is really, really, as I call it, the representation of Spanish national psyche. It had a very prominent symbolic role in Catholicism because Spain was under Muslim rule for many centuries. And then finally, the last Muslims are being expelled in the 1490s with the conquest and Jews are being expelled a lot of them, in fact go to Istanbul, Muslims are being expelled or they're forced to convert. So how do you tell who is a true Christian? How do you tell someone is not a hidden Jew or a hidden Muslim? You make them eat ham, right? So, gammon very early and sinisterly feature than a lot of Inquisition proceedings, which are very strange documents. I mean, they're really weaponize food to root out false converts. So, some woman tells on a neighbor on the village neighbor, oh, she must be a Jew, secret Jew. Why? Because, you know, I was making pork stew and she covered her nose, and Italy, you know, this could be this could get your waterboarded. So, hanging gammons, in front of taverns, and even in front of houses, becomes a symbol of being a true Christian. So, the Inquisition is a very scary thing and how it relates to food is kind of fascinating.

CK: Okay, give advice to me, or anybody who travels a lot. So, let's say I show up in Oaxaca, I show up in Rome, or I show up in Bangkok. How should I think about travel and food? Should I go there to worship it? Should I just have no, what I try to do is have absolutely no presumptions of what it is, and just experiencing it, do do some other ways of thinking about how food travel should be done the right way, or the most compelling way.

AB: What I suggest, you know, what food travel does is read a good book or several, not just about the food of the regions and the places, but also about politics and histories, because that makes you understand food in a very different context. I mean, does knowing that Pad thai is in a way an inauthentic dish, does it change it? No, because it's been a long time, and it evolves and becomes part of the culture and the same chutney that got transformed in its colonial journey. Is it an authentic? No, it is what it is. Anyway, I came to this project, very critical of nationalism, and of, you know, jingoism that is associated with it. And I came up with more respect for what people have to say about themselves. Because it's always, it's always an exchange, and try not to fall for the stereotypes but also understand that these stereotypes are powerful, and they're powerful to people themselves. You know, the Mama Mia Italians, the Italians kind of propagate this stereotype, right? You know, there's a lot of back and forth.

CK: Yeah, I agree with that. I, for me, it's when you go and cook with someone. It's the personal experience of being in a kitchen with someone. It isn't about the dish so much. It's about the preparation of the dish, and what it means to the family and those memories. So, it's intensely personal. It's not national. And that's where I think food gets really interesting. So, you're talk about Ukraine, for obvious reasons. And we were there recently, actually, and there seems to be a shift back to purely Ukrainian dishes, not Russian Ukrainian dishes, but you talk about borscht. Borscht is like hummus, right there's a million variations on the theme. But could you talk about borscht?

AB: Yeah, borscht is like hummus also because it's being claimed by different cultures. And borscht, probably most likely originated in Ukraine. But during the Soviet era, there was kind of a pan soviet dish, everybody ate it, and I grew up eating it in Moscow. My mom made it. And then I have a pot of borscht made by my mom, sitting in my fridge, and you know, something that represents home and my own identity, whatever it is, and the war starts. And I mean, seeing all the crying and just the panic and the horror that will felt, I'm suddenly asking myself, who does this dish belong to because it's being claimed by Ukraine, and by Russia, and the so the whole idea of, you know, cultural ownership of national dish of who can claim a recipe, suddenly, it lands on my own table, with just this visceral explosive intensity. And so, it just reminds you how complicated identities are because we consider ourselves Russian Jewish, American, even though my mum was born in a modern day in Ukraine, we’re Russian speakers. And suddenly, I don't want to be Russian anymore. I don't want to speak the language of Putin, and of aggression, and I don't want to think of borscht as Russian anymore, which means negating my own past. So, at the end of the book, I kind of decolonize myself, by thinking about borsch in Ukrainian I started reading Ukrainian learning Ukrainian, talking to Ukrainian people about more than means to them, and not what that means to me as part of my past. And the book ends with us inviting Ukrainian friends who were afraid, didn't want to speak to us because we're Russian, culturally Russian. And so, we all share borscht together. And we wonder if Russians and Ukrainians will ever eat again. And the answer is, I'm afraid not anytime soon.

CK: Anya, it's been really a pleasure. I love the book. I love the fact you're thinking about this in an original way. And I think the food world it's time we changed and thought about things a little differently. Thank you so much been a pleasure.

AB: I love talking to you, Chris. Thanks so much for having me.

CK: That was Anya Von Bremzen author of National dish Around the World in Search of Food History and the Meaning of Home. Every time I hear someone in the food world use the term authentic, I cringe authentic Pad Thai, authentic Montenegro, authentic pizza, authentic three cup chicken. The problem is the dishes have a complicated and diverse past. And of course, every recipe is made differently from household to household from hummus to Baba ghanoush. So, if I'm asked what is an authentic apple pie, I really wouldn't know where to begin. Cooking is like quantum mechanics. The more you look at a dish, the less you seem to know. I'm Christopher Kimball, you're listening to Milk Street Radio. Now let's head into the kitchen with JM Hirsch to talk about this week's recipe. Thai salad rolls. JM how are you?

JM Hirsch: I'm doing great.

CK: So, a little nomenclature. We're talking about Thai salad rolls today. Is that very similar to a let's say Vietnamese summer roll, salad roll, summer roll what's going on?

JM: Yeah, essentially, but also not, which is kind of confusing. And that really sums up my experience with the Thai salad rolls. I arrived in Bangkok and was utterly perplexed. So traditionally, spring rolls and summer rolls are different things. Spring rolls are made with flour wrappers, and are usually fried summer rolls are fresh, and usually use a rice paper wrapper. But here in the US, we tend to use the terms interchangeably. And then to make it even more confusing in Thailand they don't call them spring or summer rolls. They call them salad rolls. But unlike Vietnamese summer rolls, which tend to favor produce as the primary filling, in Thailand, the salad rolls actually are robust and meaty. So yeah, I was confused.

CK; So, they're totally different. Okay, (exactly.) So you went to Thailand, and you started by visiting, I think a family, but they made the rice paper from scratch, which is really interesting. How do they do it?

JM: Yeah, that was really cool. Now I have seen rice noodles made. And that's where they make a slurry of rice and water and then stretch it out over a mat and let it dry in the sun. And then they slice them up. But this was a completely different process. It's still the basic slurry of rice and water. But instead of spreading it out and drying it in the sun, they almost treat it like a crepe, but the cooking surface instead of being a pan. It's actually it's kind of like cheese cloth that stretched taut over a pot of boiling water. And so, they steam to cook and they're done within seconds. And they're not they're never dried actually. And they're made fresh. And then they're used fresh to wrap the fillings. It was really such a tender delicious wrapper so much better than the dried ones we get. I wish we could get the fresh.

CK: This is one question. You live in Bangkok; you're not making them yourself. You just go buy them fresh every day when you need them or what?

JM: I think so I think this is considered kind of just a lunch item, right? I never actually saw them on the menu of a restaurant. I always saw them at markets where you would just buy it like we would get takeout sushi, you know, and nibble on them as you walk around the market and a wonderful way.

CK: So, onto the recipe. I assume that dipping sauces you know, like juice and sugar and soy sauce or fish sauce probably. But what about the filling?

JM: Well, this is what's really interesting is, you know, I find that summer rolls tend to be a little light, you know, it's mostly lettuce and carrots and some cucumber or maybe occasionally some shrimp or whatever. And they're nice, but they're a little light. Thai salad rolls are quite robust, but they're not heavy. And the reason they're robust both in flavor and kind of substance is they contain ground pork that's been very well seasoned. And then it's mixed with rice and scallions and then some lettuce and carrots and basil go in. And the result is like I say a very robust flavor profile but also just kind of meatiness and savoriness to it. That's really nice and it's so much more satisfying than kind of the lighter summer rolls.

CK: So, if you want a hardier, a more substantial, maybe more interesting version of the summer roll. Thai salad rolls direct from Thailand JM. Thank you so much.

JM: Thank you. You can get the recipe for Thai salad rolls at Milk Street Radio.com

CK: This is Milk Street Radio after the break Dan Pashman takes a stand against elaborate school lunch, that's coming up. I'm Christopher Kimball, and you're listening to Milk Street Radio right now, my co-host, Sara Moulton and I will be taking a few more of your cooking questions.

SM: Welcome to Milk Street who's calling?

Caller: Hi, this is Jessie from New Jersey.

SM: Hi, Jessie, how can we help you?

Caller: I saw black chicken used on a cooking show and I found one at a local Asian market. It's currently in the freezer and I was wondering if you had any recipe recommendations, and if I can use it for stock and schmaltz afterward,

SM: Schmaltz so now you're talking. Schmaltz, for anybody who doesn't know is chicken fat. You know, in the old days in the Jewish delis in New York City, that would be the fat of choice they put on the counters, you were supposed to spread schmaltz on your toast. Anyway, what you're talking about, I believe are silky chickens is a particular kind of chicken. Apparently, they're nice chickens from what I understand. Under their feathers they're black skin and black bones and darker looking meat. You know, they're popular for use in Asian cuisines and do tend to be a little gamier, they're leaner than regular chickens. So, I would use them mainly in braise like dishes, you know, or soups, and certainly use the bones for stock because you want to do that anyway, so we're going to make a soup. And let's see what Chris has to say.

CK: Well, my mother used to raise silkies.

SM: Did she really?

CK: She had all different colors. Is it true?

SM: Is it true? They were nice chickens.

CK: They look nice,

SM: Or were they friendly?

CK: I didn't spend a lot of time talking to them.

SM: Okay. All right.

CK: Anyway, they're small. They're not designed for, you know, plump breast meat or anything. They're not meat birds, and they would be very gamey. It'd be more like the difference between beef and venison or something. There used to be stewed or used in a soup or something like that. If you wanted a rich broth. That's probably how you would use so strong flavor.

Caller: Okay, great.

CK: Yeah. All right.

SM: Yeah. And Jesse, let us let us know when you finally cook it what you think.

Caller: I will thank you so much.

SM: Okay. Take care.

CK: Take care. Bye. This is Milk Street Radio. Sara and I are here to answer your cooking questions, give us a call anytime. 855-426-9843 one more time 855-426-9843 or email us at questions at Milk Street Radio.com. Welcome to Milk Street who's calling?

Caller: This is James Cantrell.

CK: How can we help you?

Caller: I've always been frustrated. My wife and I love to eat shrimp. Pretty much any way you want, except with better. My question is, why do so many restaurants leave the tails on there? Why did they not remove the tail? Is it aesthetics or what?

CK: Well, one reason is they look bigger. So maybe there's more perceived value with the tail on if they're fried like a tempura, I think it's fine. I think also, they're good handles, right? It's like a drumstick, you could pick up absolutely for shrimp cocktail. But, but there's no other reason that that is just purely aesthetics, I guess. Okay, of course, the other question is, you know, you can also leave the heads on, and some places do that as well, but I think it's just a function of yeah, well, one thing about head on shrimp though, if you're going to make like a like stock for like 20 minutes stock for whatever getting the heads on, it's great, because that adds a lot of flavor. But I would say it's purely either functional to pick them up or it's, it looks nice, Sara?

SM: I think it's pure laziness. That's what I've decided. Yeah.

CK: She’s she's having a dark day here at Milk Street.

SM: No, I think it's I mean, I'm sure both of the things that Chris said are true. But also like, when I'm faced with this dilemma, I really want to try to get the peels all the way off to the very end, because there's meat in that tail. And why do you want to leave the meat there, but the trouble is, it's very hard to get it out. And then your nails, you smell like shrimp, because you've got your nails under that skin to get the shell off. I mean, and if you cook it and leave it on, then you're also not going to get you know, you look at a pile of those tails on a plate, and there's meat still left in there. But I think it's because it's so much work. Really.

Caller: I'm not so concerned about the meat still left in there as you're sitting there with a knife and a fork trying to extract trim from the tail. And I just thought, well, why did they do this? Well, so I thought I'd give you guys a call.

SM: Good question, James.

CK: Excellent question.

SM: We've never gotten that one before. So, thank you.

CK: You're lazy. That’s the answer. Take care.

Caller: All right.

SM: Bye.

CK: You're listening to Milk Street Radio. Now it's time to hear from one of our regular guests. Dan Pashman. Hey, Dan, what's up?

Dan Pashman: Well, Chris, I'm feeling a little bit frustrated this week, because I spent another week making school lunches for my kids and also looking at social media and seeing the school lunches that other parents some school lunch influencers are making. And it's very irritating. Do you have this issue? Like, are you on school lunch duty?

CK: No, my wife actually does it. And about six months ago, she went to pick up the kids and a teacher took her aside and said, they were quite disappointed in the quality and the healthfulness of our lunches. This is like I just pointed out this is sort of an international school, right? Everybody has to be just right. So, my first instinct was to pull the kids out of school. But my wife decided to stick it out.

DP: Do you know what it was that they brought that attracted the teacher’s ire?

CK: Well, we do actually have these little cheddar bunny packets and stuff.

DP: They're like cheddar goldfish.

CK Yeah, cheddar goldfish but their bunnies. Yeah, that probably was, you know, I guess they're more carrot and cucumber slices now, but it is a problem five days a week, you you've got to have lunch ready, right?

DP: It's a ton of work. But you know, this issue that your wife had leads perfectly into what I want to talk about, because you know, it's become a huge thing on social media, for parents to make these incredibly elaborate school lunches, sometimes their bento boxes and as it's just like, cucumbers carved like penguins, or whatever it may be. A lot of it is under the pretense of like, we're going to make lunch fun, and that will get our kids to eat healthy. Look, if it makes you happy, do whatever you want. But sharing it on social media only serves to put pressure on other parents and make it feel like everybody's falling short. So, I just want to speak out against this trend. There was one mom who does this on social media, who estimated that she spends four to five hours at the start of each week on meal prep for her two kids. (What? No) No, look, I understand that healthy eating is important. And I understand that obesity is a legitimate concern. We all want our kids to be healthy. But this idea that the only way to get your kids to eat healthy is to basically quit your job, so that you can do nothing but make lunches for them is ludicrous.

CK: So, let's get to the goods here. So, what is it you make your kids for lunch? What is your solution here?

DP: So, for some weird reason, my older daughter doesn't like sandwiches. I don't understand how this happened. But she likes a wide range of things. Like any kind of noodles, you can put vegetables and actually you can put tofu in it. She'll eat it. It's often leftovers like, to me that's the thing. Like if you're making a fairly healthy dinner, just make extra and give the leftovers for lunch the next day like then you're not having to make a whole other meal. There's no need to carve your cucumbers into the shape of a penguin. Just serve leftover dinner.

CK: Yeah, I totally agree.

DP: The one sandwich we've been able to get both kids to eat is just simply like a hallah roll. With cheddar cheese and lettuce.

CK: Well, that’s not bad.

DP: No that’s fine. And look, there's no condiment on it. It's not the most exciting sandwich to me, but they eat it. It has some lettuce in it. And I haven't gotten pulled aside by any of the teachers.

CK: Did you ever try something more adventurous in the early days?

DP: I did experiment recently. I bought some edamame noodles, edamame pasta like gluten free because it's it's has a lot of protein and fiber, and I thought like my kids eat a lot of pasta. If I can get them to like this and I made it in the first bite I took I was like this is delicious. I love edamame. I love the flavor. It's sort of like toasty roasty delicious. But something weird happened like the more I ate it, the less appetizing it was. So, I had my daughter try one bite. She said oh, it's really good. I really like it. I sent it to school with her for lunch the next day and she came back with the container only half eaten. And she's like, Yeah, the more I ate the grosser it became.

CK: Well, I just like to make a comment that when I went to elementary school, there was a full cafeteria, they must have had 10 people there. Everything had cold dishes, hot dishes. I mean, you could get a bologna sandwich if you wanted but, you know, there was a lot of food. And it was, you know, it was pretty good food. And I gather, they're very few of those places left. I mean, things are heated up, they don't have full kitchens. People have to bring their lunches. The fact that you can't feed kids a decent lunch, which by the way they do in Mexico, and they do in France, they do in most of the countries. We're basically at the bottom of the list. I think we spend $1.23 per kid for lunch in a public school. I think Mexico is 3.50 you know so I don't get it. It seems to me that would be a priority as a nation, Right To feed the kids well.

DP: I agree.

CK: That was my little speech. I stuck that in there.

DP: No, but I agree 100% It shouldn't all be on parents. And it's, it's unfortunate that it's not a higher priority.

CK: So, to summarize, don't carve cucumbers into penguins don't put your lunches on social media. And if the school says it's not sufficiently good for the kid, ignore them. (Yeah). And hopefully my kids won't get expelled. Thank you.

DP: Yeah, good luck on that.

CK: That was Dan Pashman, host of the Sporkful podcast. That's it for today. You can find all of our episodes at Milk Street Radio.com or wherever you get your podcasts. You can learn more about us and here at Milk Street at 177 Milk street.com. There you can become a member and get full access to every recipe, access to all of our live stream cooking classes, and free standard shipping for the Milk Street store. You can also learn about our latest cookbook Milk Street Noodles. You can also find us on Facebook and Christopher Kimball's Milk Street on Instagram at 177 Milk Street. We'll be back next week with more food stories and kitchen questions and thanks as always for listening.

Christopher Kimball's Milk Street Radio is produced by Milk Street in association with GBH, co-founder of Melissa Baldino, executive producer Annie Sensabaugh. Senior Editor Melissa Allison, producer Sarah Clapp, Associate Producer Caroline Davis with production help from Debby Paddock. Digital editing by Sidney Lewis, audio mixing by Jay Allison and Atlantic Public Media in Woods Hole Massachusetts. Theme music by Toubab Krewe. Additional music by George Brandl Egloff. Christopher Kimball's Milk Street Radio is distributed by PRX.

In this episode

Simple, Bold Recipes

Digital Access

- EVERY MILK STREET RECIPE

- STREAMING OF TV AND RADIO SHOWS

- ACCESS TO COMPLETE VIDEO ARCHIVES

Insider Membership

- EVERYTHING INCLUDED IN PRINT & DIGITAL ACCESS, PLUS:

- FREE STANDARD SHIPPING, MILK STREET STORE,

to contiguous US addresses - ADVANCE NOTIFICATION OF SPECIAL STORE SALES

- RECEIVE ACCESS TO ALL LIVE STREAM COOKING CLASSES (EXCLUDING WORKSHOPS & INTENSIVES)

- GET YOUR QUESTIONS ANSWERED BY MILK STREET STAFF

- PLUS, MUCH MORE

Print & Digital Access

- EVERYTHING INCLUDED IN DIGITAL ACCESS, PLUS:

- PRINT MAGAZINE SUBSCRIPTION

- 6 ISSUES PER YEAR