Your email address is required to begin the subscription process. We will use it for customer service and other communications from Milk Street. You can unsubscribe from receiving our emails at any time.

The Hot Basil Restaurant For People Who Like Spicy Food

Back to March-April 2017

During three days in Chiang Mai, the largest city in northern Thailand, I learned that it takes two hours to cook chicken feet. That dried chicken blood is sold in bricks. That the car wash parking lot is used for cockfighting. That cold ash is poured over live coals to moderate a grill’s temperature. That pork intestines are chopped and added to larb, a minced pork dish. That a wooden mortar and pestle, instead of stone, are used when one wants to pound flavors into foods such as papaya. And that one must be sure to say “mai wan” (Thai for “not too sweet”) when ordering a cocktail, because bartenders tend to overdo the sugar.

Chiang Mai is a city of over 1 million people, most of whom live in low-rise buildings; endure modern traffic jams; frequently travel by scooter or auto rickshaw; shop in large indoor markets, such as Sanpakoi; love to have their wedding photos taken at the city’s main gate, Thapae; enjoy variations in texture, including gnarly bits of chicken; and sell eggs in bright colors such as pink. You can shop for Hello Kitty fashion accessories at the mall. On weekends, karaoke is popular, often at home with drinks and friends. And if you do something fast and sneaky, they say you are “stealing the chicken.”

Everything has variations. There are three types of soy sauce: white, black and sweet. There are over a dozen varieties of durian, some of them delicacies—though I still think durian tastes the way septic tanks smell. There are six different words for eating, including terms reserved for monks (“chan”) and the royal family (“savoey”). The Thai people greet each other with hands in prayer formation (the “wai”), chin-high, with a gentle nod of the head; minor variations telegraph a range of different sentiments. Higher hands and deeper bows confer more respect. Tourists are told not to initiate the wai, but it is an insult not to return it.

Even a short trip to Thailand offers the suggestion of another world beneath the surface.

I stumbled across a Chinese temple at a large indoor market. Looking over a fence outside Chiang Mai, I saw an ancient panorama—fields of rice and corn being hoed and irrigated by hand with the mountains of Burma high and hazy in the distance. A small outbuilding turned out to be a spirit house, constructed for ancestors whose spirits were displaced when the main house was built.

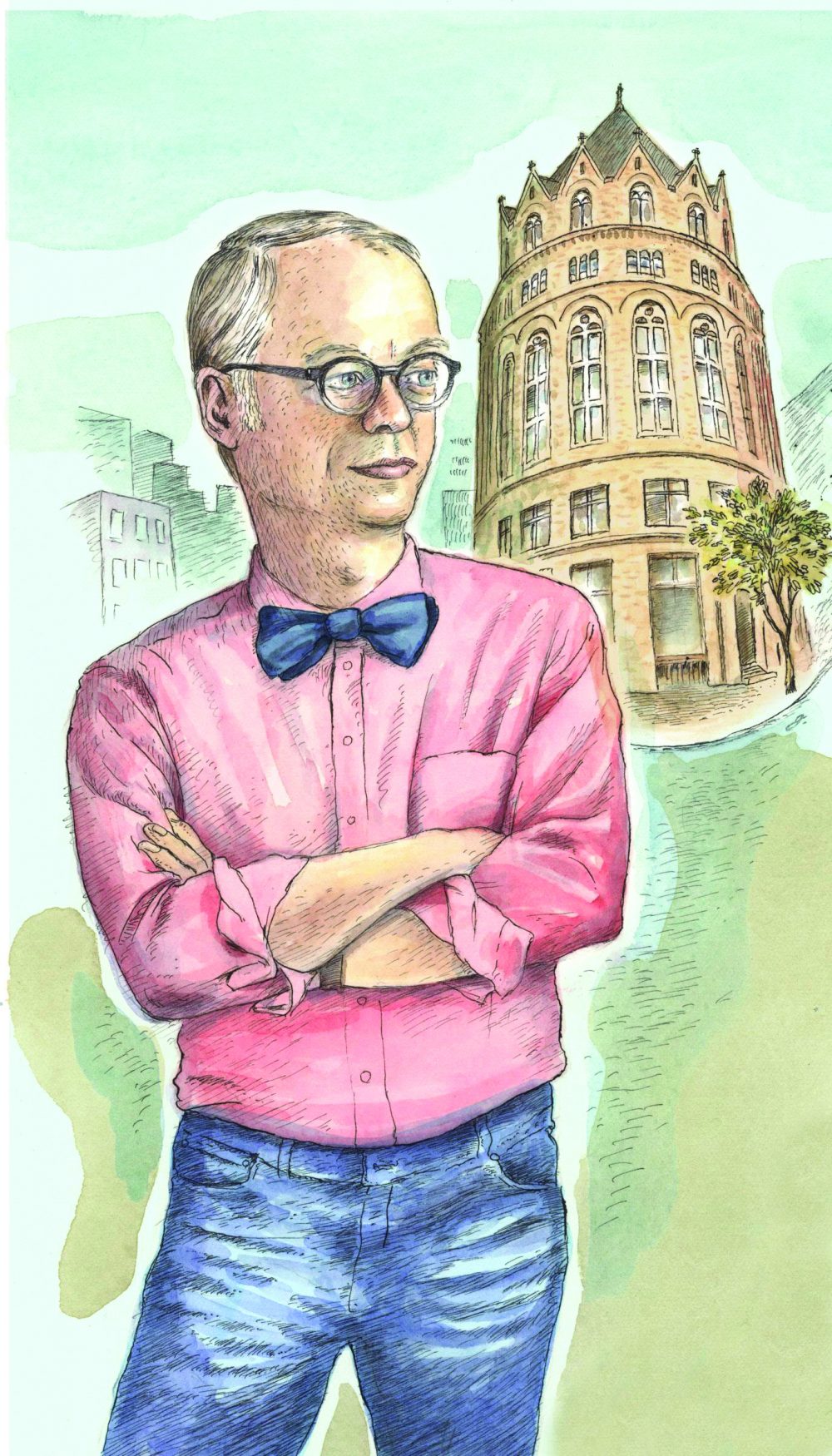

The frenetic undercurrent of modern life, even in the clamor of a big city, seemed just a step away from a quiet temple or a seat at Jok Sompet, where one enjoys a bowl of rice porridge with pork balls, fried garlic, cilantro and white pepper, or a flash-steamed mess of greens at The Hot Basil Restaurant for People Who Like Spicy Food, served with garlic and red chilies with soy, fish and oyster sauces. Restaurants have their own structure, their own ecosphere, from the silent empress dowager behind the cash register at Hot Basil to Mame Tu at Jok Sompet, the reigning doyenne of porridge. Charming, energetic and joyfully in charge.

Is it Buddhism? The calm is not to be mistaken for subservience or acquiescence. It comes from inner strength, a conviction that the past is alive in the present. Ghosts in the West are the stuff of stories. In Thailand, ghosts inhabit the temples and spirit houses. One never walks alone.

I left Thailand with soft, enduring memories. Twilight over rice fields. The scent of lemon grass. The deep shade of tamarind trees. The taste of red chilies, cilantro root and fresh turmeric. A dead chicken with a coiled, snake-like neck. A house cat sitting on a roof, alert for an offering of food. Slices of speckled dragon fruit and oblong tubes of papaya at breakfast.

When I arrived at the Chiang Mai airport, I met Nok, the charming, soft-spoken local fixer who was our guide. She greeted me in the wai fashion. I didn’t know how to return the gesture.

Three days later, as we were saying our goodbyes, I bowed and prayed to Nam Tan (a nickname that translates to “sugar”), one of the local crew, in my best imitation of wai. I had learned something—just a gesture, but enough to remind me that I was bringing back something precious from Thailand, something old and something new.

March-April 2017