Your email address is required to begin the subscription process. We will use it for customer service and other communications from Milk Street. You can unsubscribe from receiving our emails at any time.

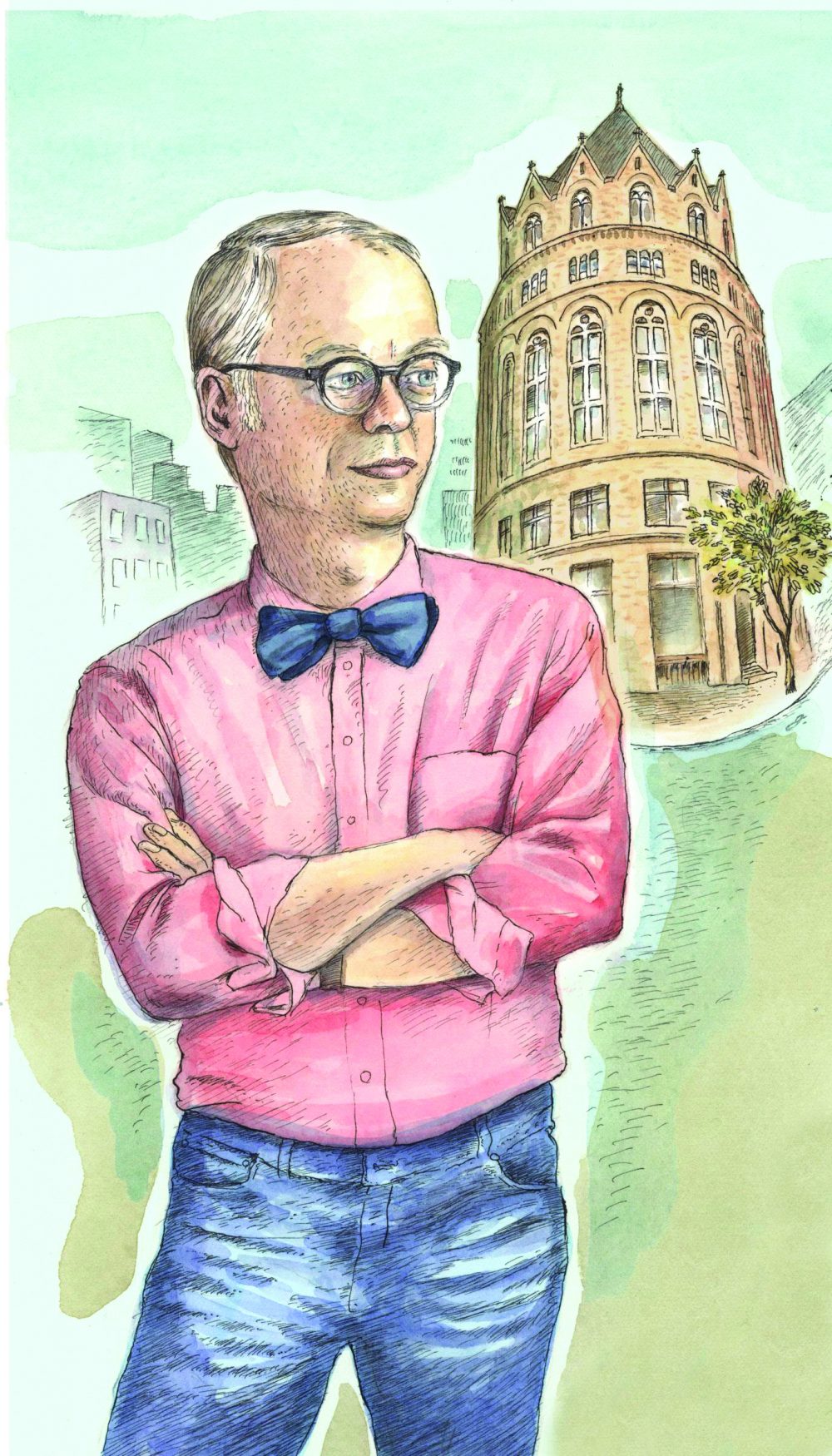

Everything I Know About Food Science I Learned in Kindergarten

Back to May-June 2021

This is not going to be a popular column. I tell you this so you can stop reading and cue up “Bridgerton” or post photos of your cat on Instagram. You might end up less vexed.

How does no-knead bread work? Why does instant yeast not need to be proofed? Why do marinades do a lousy job of imparting flavor? Why does cream of tartar stabilize whipped egg whites? All good questions, no doubt, but after 40 years in the food business, I vote to take the science out of food science.

As Harold McGee points out, food science is real science, and, as you know, the vast majority of self-appointed experts are not in fact scientists (including yours truly). Let’s take that no-knead bread example. For years I have explained that gluten is made of glutenin and gliadin proteins in flour, which, when water is added to the mix, are able to link together to create gluten.

Fair enough. But what is glutenin, you ask? According to Wikipedia, “Glutenins occur as multimeric aggregates of high-molecular-mass and low-molecular-mass subunits held together by disulfide bonds.” I understand that about as well as I can lecture on dark matter. Instead, why not say, “Water + Flour + Time = Stretchy Dough”?

And I’ve answered countless questions regarding the Maillard reaction, saying that, in the presence of heat, a reaction occurs between amino acids and sugars. But, once again turning to Wikipedia, “The reactive carbonyl group of the sugar reacts with the nucleophilic amino group of the amino acid and forms a complex mixture of poorly characterized molecules responsible for a range of aromas and flavors.”

In other words, this is a messy business. Even scientists don’t fully understand Maillard. (That’s why those molecules are “poorly characterized.”) How about: “Meat + Heat = Color + Flavor”?

You could do the same with emulsions (tiny droplets of one thing in a sea of another), convection (heat through air and liquid), gelatinization (starches swell with water and heat), barbecue (big meat, low and slow), marinating (it doesn’t work), brining (it does work), and molecular gastronomy (Escoffier managed without it).

There is a joy and effervescence to cooking that belies food chemistry. Science and art are not mutually exclusive, but as Thomas Keller said, “A recipe has no soul. You as the cook must bring soul to the recipe.” My apple pie ought to reflect my past, lessons that extend beyond the table. “Joy of Cooking” may be a dated kitchen reference, but Irma Rombauer got it right with the title. Cooking is a passionate act, not a step-by-step exercise in food engineering.

And now, if you are still with me, comes the moment when you conclude that I’m experiencing a form of late-life crisis, a desperate cry for help in the guise of an editorial. Here it is: Cooking is about people, not science. Cooking beans with Eduardo García on a chinampa in Mexico City. Feasting with Reem Kassis and her family in the Galilee Valley. Making mujaddara with Hussein Hadid in Beirut. Preparing thieboudienne with Pierre Thiam in Dakar. Placing tortillas on a comal over a wood fire with Reyna Mendoza in Teotitlán del Valle. Food reflects culture, history, community, family, friendship—all the things that make us human.

Two weeks ago my wife, Melissa, and I made pretzels. No, I did not manage to roll out the thin logs of dough to 30 inches (maybe 20?), and they baked up looking like Christmas wreaths fashioned by inebriated elves. But the warm, soft rolls were so good that they barely lasted the afternoon. Damn the science of alkaline solutions to induce browning. We made pretzels!

I am excited to get on the road again for the people. The tables I’ll sit at, the stories I’ll hear, the rhythm and poetry of languages I don’t speak. Give me a glass of mezcal raised in welcome. Or let me lunch again with Kamal Mouzawak, who started the first farmers’ market in Beirut, Souk el-Tayeb, so I can listen to his passionate belief in the power of food to heal nations.

I’m not saying knowing a little food science is a bad thing. It’s just not the thing. Cooking flows through us, supports us, wraps us in a place in time. And if you make a mistake—the cake falls, the roast is dry, or the mashed potatoes are lumpy—raise a glass to fate. Remember, it’s the people sitting at the table that matter most. As for the science? Let it go.

May-June 2021