Your email address is required to begin the subscription process. We will use it for customer service and other communications from Milk Street. You can unsubscribe from receiving our emails at any time.

Food Without Borders

Back to November-December 2018

I recently interviewed Anissa Helou, the London-based author of nine cookbooks, including “Lebanese Cuisine” and “Mediterranean Street Food.” Her latest book, “Feast,” is a culinary tour of the Islamic world, which may center around the Middle East but which stretches from Syria to Indonesia, from Zanzibar to Uzbekistan and beyond.

Helou pointed out that the Levant—a historical reference to a large swath of the eastern Mediterranean—has many shared culinary traditions, yet each region has its own versions of particular dishes.

Flatbreads are a good example. Start with pita bread dough but use different shaping techniques and you end up with wide, thin Turkish yufka or Lebanese markouk—a flatbread that doesn’t puff. And then there are Somalia’s spongy pancakes (anjero), sometimes made with sorghum flour; Iran’s long, ridged, oval-shaped barbari bread; and Turkey’s soft, thick, boat-shaped pide, used as a base for pizza-like toppings.

There is also a range of multilayered breads that require great skill, including m’hajib from North Africa (folded like an envelope before baking) and bint el-sahn (thick, flaky and honeyed) from Yemen. And there is Uzbekistan’s non, stamped with a chekish, a wooden mallet spiked with metal nails. The list goes on.

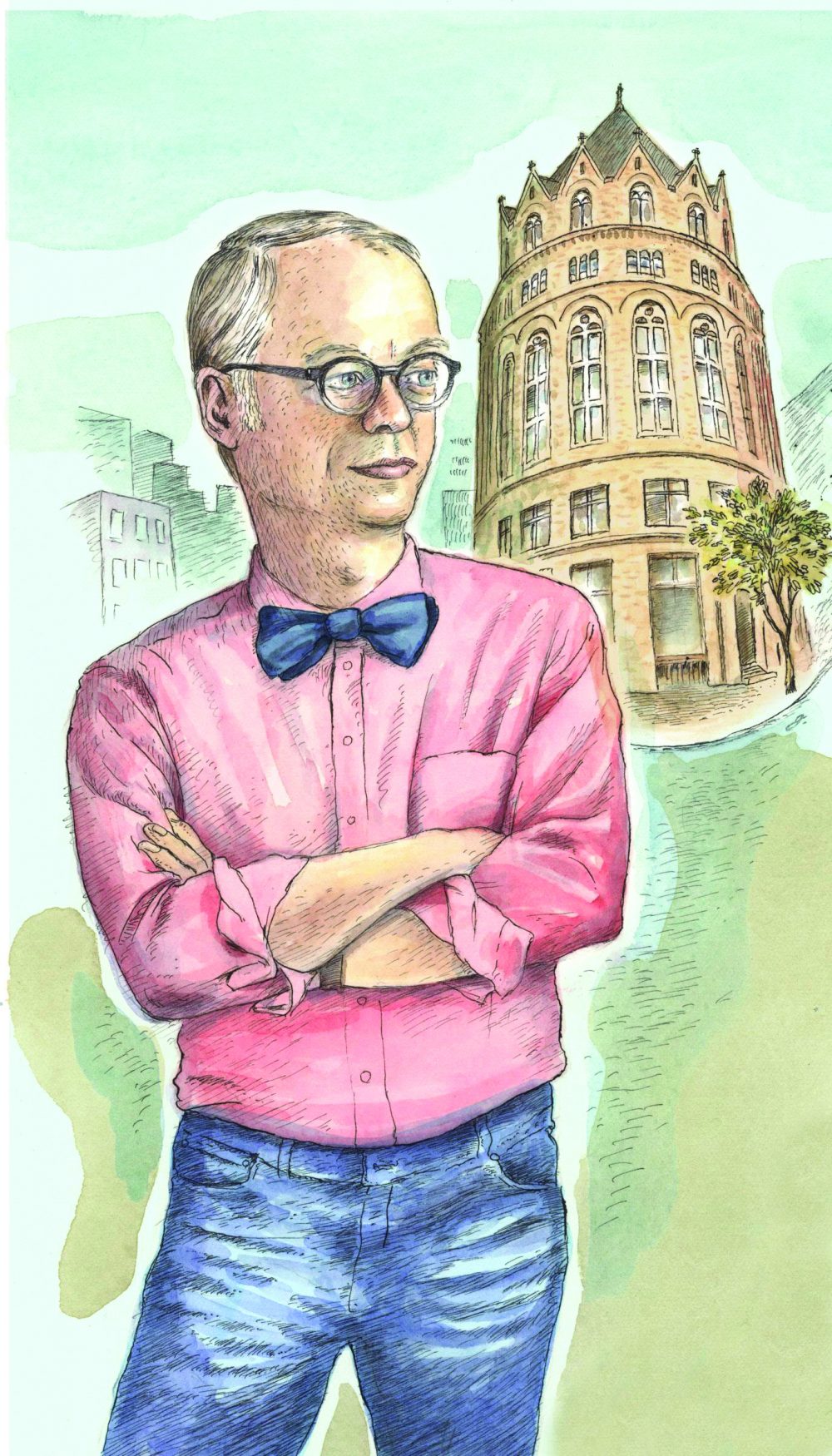

Last year, I spoke with Marhaf Homsi, a Syrian baker from the city of Hama who fled the civil war to relocate to Brooklyn. He runs his business out of his apartment, making Syrian specialties, including baklava, for mail order. Syrian baklava uses large, coarse pieces of nuts and almost no sugar syrup. It’s almost savory; nothing like the sweeter, more finely ground versions from Istanbul.

Recipes evolve over time, their characteristics changing. In Taiwan, beef noodle soup is arguably the national dish, yet history tells us that its Taiwanese debut dates only to the arrival of millions of mainland Chinese to Taiwan in the late 1940s. Likewise, in Thailand and Vietnam, noodles are essential to dishes like pad Thai and pho. But they are a Chinese invention, of course, one that’s been exported around the globe.

Recipes are performance art. They adapt to the local audience and culinary offerings. Gonzalo Guzmán of Nopalito in San Francisco defines Mexican cooking as corn tortillas. Even a recipe that simple has variations: white, yellow or blue corn, for starters. A Guatemalan tortilla is thicker than the tortillas Guzman grew up with in Veracruz.

In Morocco, a tagine is not a recipe per se; it’s a rough guide, one that is sometimes made with meatballs instead of chicken or lamb. The same is true of kibbeh and biryani (Helou details variations from Awadh, Hyderabad, Calcutta, Malabar and United Arab Emirates), to say nothing of curry or Indian cooking in general. The cooking of northern India (the most typical export to the U.S.) is vastly different from the dishes made in the country’s southern states.

As different regions treat the same recipe differently, so too do different towns, villages, even families. The author of “Five Morsels of Love,” Archana Pidathala, told me her cookbook was a tribute to her grandmother Nirmala’s unfinished recipe collection. These were personal family recipes, not “Indian” cooking. In the Middle East, there is za’atar, ras el hanout and berbere, but Reem Kassis, author of “The Palestinian Table,” nonetheless opts for her family’s custom nine-spice mix.

As people travel from one place to the next, chickpea flour turns to masa turns to wheat flour. In Peru, Italian immigrants made pesto with spinach leaves instead of basil, and Chinese immigrants introduced cooks to stir-frying. Today, lomo saltado (a stir-fry of beef and tomatoes) is considered a local dish. Gumbo, as made today in Senegal, is mostly built on dried, smoked and fresh fish that’s mashed with okra to make a base—nothing like the dark roux gumbos of New Orleans.

Recipes are not immutable. They change their shape, moving around the world, absorbing local influences and introducing new civilizations to old ones through hospitality. They are cultural ambassadors. Cooking is food without borders; it’s the new immigration. And that just might be the saving grace of this troubled century.

November-December 2018