Your email address is required to begin the subscription process. We will use it for customer service and other communications from Milk Street. You can unsubscribe from receiving our emails at any time.

Ode to Madeleine

Back to November - December 2023

On a recent trip to Paris, I stopped by Jouvence restaurant, where, seven years ago, chef Romain Thibault began serving baked-to-order warm madeleines for dessert. This was at a time when the French started craving updated classic bistro dishes, including fluffy rice pudding served with a burnt caramel cream and a bowl of broken nougat (chef Stéphane Jégo at L’Ami Jean); Paris flan, a deep dish slice of custard pie (Stéphane Jimenez at Amazonia); and a new-style French onion soup served with a crown of cheesy puff pastry (Hortense Thoreau at Bichettes).

It is easy to jump on a bandwagon by assuming that this is in fact a citywide trend, since you can still find pastry chefs in Paris making molten lava cakes, lemon tarts disguised as towers of Bavarian cream and praline chocolate cookies with an ice cream center. But it does say something about the times we live in. People want to connect more deeply with their food; less entertainment, more substance.

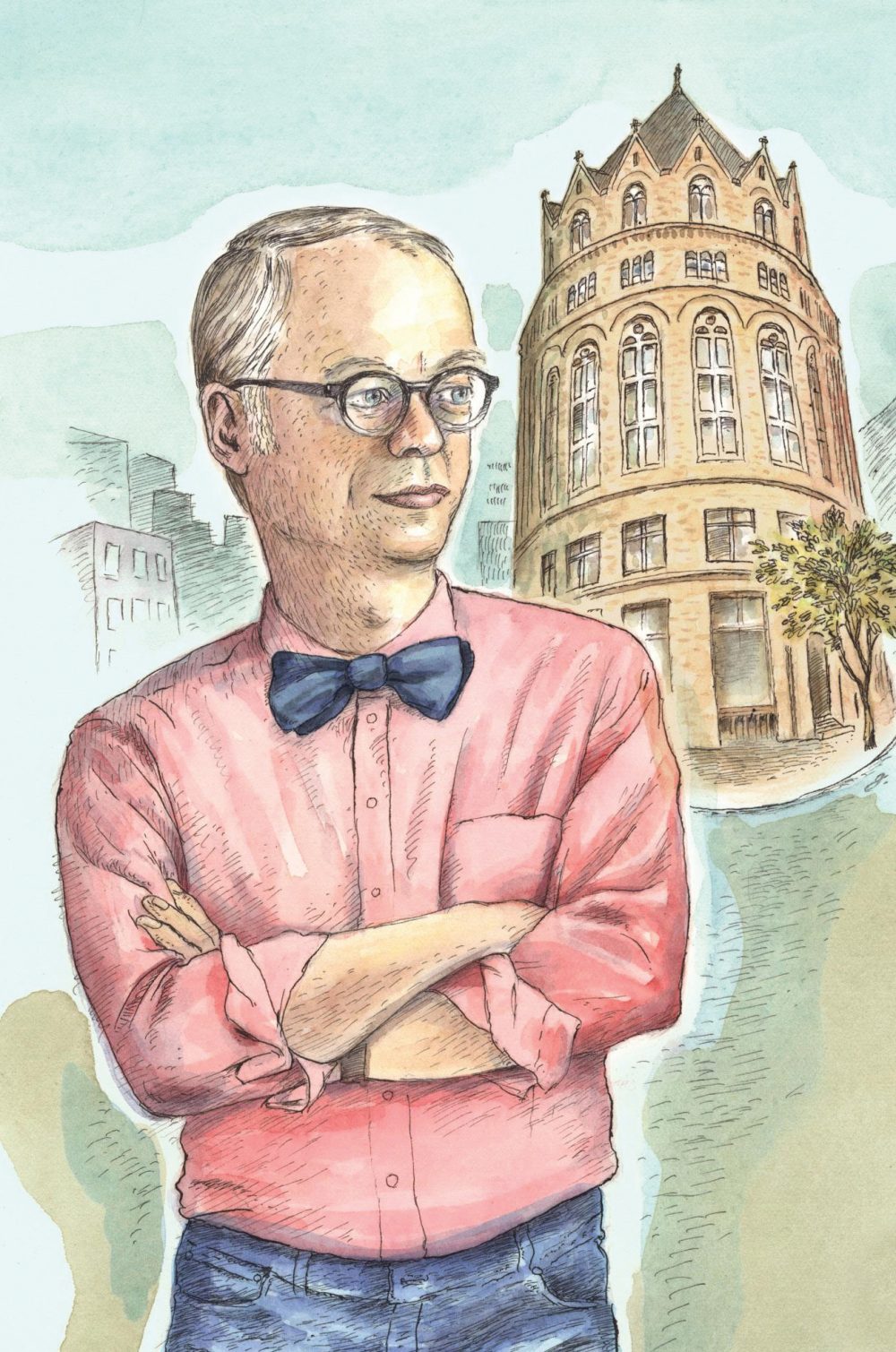

The chefs themselves illustrate the point. Watching Jégo, who is every bit as animated as SpongeBob SquarePants, wax euphoric about how to perfectly cook rice in milk 18 years after his culinary breakthrough is to witness the merger of recipe and soul. Jégo has been transformed by rice pudding; he lives and breathes his creation like Pygmalion. This simple homespun dessert got a three-star makeover and has been on the top desserts list in Paris for years. Eve Thibault feels a sense of ownership (or perhaps parental pride) with his warm madeleines—he bakes them crispy on the outside and slightly undercooked inside, a far cry from the sponge cake-like offerings usually associated with this iconic French offering.

Although the notion of recipe ownership, especially among home cooks, is questionable (a recipe cannot be copyrighted for good reason—it is simply a set of instructions, a guide to making something out of raw ingredients), recipes can be personal, connecting to memory like an oyster to its shell. It may be a coconut cake served at family gatherings in Savannah, a fish boil at Halloween in North Carolina or a thick slice of freshly baked white bread with a schmear of home-churned salted butter in a small farmhouse in Vermont. But not all food memories are warm and fuzzy. I have sad memories of beaten biscuits from a funeral reception in Baltimore but joyfully remember hand-churning homemade peach ice cream in Vermont. Restaurant meals are often the occasion for engagements but just as often serve as settings for divorce. I can still taste the apricot juice from a hospital stay when I was 5 years old. And the memory of a bit of pale egg yolk caught on the stubble of my father’s chin during his last desperate weeks in a nursing home still haunts.

Food is powerful. It attaches to memory, to emotion, to opinion. I watch with more than a bit of trepidation as food has become a means of separating us from our common humanity. My food. Our food. Your food. Hey, it’s all our food! Food as politics offers a dark path; it pollutes its very nature: to bring joy, to sustain, to bind, to bring us into the moment.

Speaking of the moment, food’s greatest parlor trick is to dismiss the past and the future. I defy anyone to taste a warm madeleine, crispy on the outside, buttery on the inside, and be consumed by a sea of troubles.

Proust famously wrote about a tea-dunked madeleine, “No sooner had the warm liquid mixed with the crumbs touched my palate than a shudder ran through me and I stopped, intent upon the extraordinary thing that was happening to me.”

That extraordinary thing is the timeless power and pleasure of food.