Your email address is required to begin the subscription process. We will use it for customer service and other communications from Milk Street. You can unsubscribe from receiving our emails at any time.

January 4, 2024

Eat, Drink, Read: Dwight Garner's Obsession with Word and Table

We’re joined by New York Times book critic and author Dwight Garner. He presents food quips from his favorite writers, as well as John Updike’s lunch routine and Hunter S. Thompson’s party tricks. Plus, anthropologist Manvir Singh helps us digest the world of “meat-fluencers” and their all-meat diets; A Way with Words give credit to the Old Norse words lingering in our kitchens; and we prepare a Pakistani-Style Chicken Biryani.

Questions in this episode:

"I'm making a wedding cake and need help with my salted caramel filling consistency. What should I do?"

"How can you tell when different cheeses have gone bad?"

"How do you reheat soup with kale without it turning bitter?"

Christopher Kimball: This is Milk Street Radio from PRX I'm your host, Christopher Kimball. Long lunches, strong cocktails writers are notoriously reliant on good food and good drink. Take John Updike, for example.

Dwight Garner: He worked over a restaurant, and he said he knew when he smelled, smelled the aroma of lunch coming up it was time to quit for the day. So, he would work from eight until he smelled lunch cooking. And

CK: Don't forget Hunter S. Thompson. When he got drunk, he would just get a garden hose and spray everyone down in there. There are great photos of Hunters who are terrorizing my wife who was all five at the time. Today we're chatting with New York Times book critic Dwight Garner, about books, food and books about food. But first we're going inside the world of extreme carnivores.

Brian Johnson: What’s up primals, Liver King here we just took down a Mongolian yak and what do you think we're going to start of course deliver first because liver is king.

CK: That's Brian Johnson better known to his millions of social media followers as The Liver King. He and other meat fluence errs have gained notoriety for promoting all meat diets. They say that returning to an ancestral lifestyle has many health benefits. Anthropologists Manvir Singh investigated this claim for his New Yorker article, Red Shift is an all-meat diet what nature intended? Manvir welcome to Milk Street.

Manvir Singh: Yeah, thank you for having me.

CK: As a kid, I had lots of ways of thinking about what I would call myself as I was older, but The Liver King was never one of those things I came up with. So, who is the Liver King?

MS: Yeah, the Liver King is a phenomenon. I guess he is the executive of a number of meat, raw food, liver supplement companies. And his main tagline his main selling point was that he advocated for a return to an ancestral way of living, he put out videos of him lifting incredibly heavy stuff of eating crazy amounts of food. And he had a meteoric rise, and then a correspondingly devastating fall after it came out that his you know, ripped body was not attributable to liver as was his claim, but instead was a product of like a pretty heavy steroid regimen.

CK: Oh, that the steroids and the little chopped liver, you know, on pumpernickel, for lunch with onion, and then steroids. This is obviously connected to the Paleo diet. So, I think we've all heard of the Paleo diet, we all kind of know what it is. Could you just tell us exactly what the Paleo diet means in terms of what you eat?

MS: Yeah, so the logic of the Paleo diet is that the processed food that we consume is nowhere near the kinds of diet that ancestral humans subsisted on. And if we want to be healthy, if we want to thrive, then we need to go back to that Paleolithic diet. And the Paleo diet is a particular brand of that it's a particular interpretation. But that is at least the logic, that's the selling point of it.

CK: So, you have a group of people who claim that eating meat is sort of this be all and end all. But when people looked into it, I guess it turned out that, you know, there's no such thing as the Paleo diet. Some places, it was mostly plant based, right?

MS: Yeah, yeah. I mean, so there are different tools we have for reconstructing ancestral diets. You can look at what contemporary hunter gatherers eat, you can try to do genomic evidence. And whatever method we use suggests that the ancestral diet was much more diverse and dependent on where people were living. And I think it's also worth appreciating that there are some of these case studies that the meat fluences really like to put forward. The Inuit for example, they'll say, oh, the Inuit are a hunter gatherer population. They had nearly all meat or exclusively meat and look how well they did. But these are lifestyles that are actually much more recent than even agriculture. The Inuit have only lived in the Arctic for a couple 1000 years. So even the all-meat diets that influencers really like to point to seem to be just as modern as any of the agricultural diets that they like to rail against.

CK: So, there are studies, which are I'm sure you're aware of the do say that meat diets are positive. Harvard did one in 2020 with 2000 participants, and the results were pretty positive. 100% of diabetics came off of injectables. 92% came off of insulin, 90% improvement in all diseases, average weight loss 20 pounds, I would assume though, they're equal studies on the other side, which do the same thing. In other words, what do you do with all He studies which seemed to conflict.

MS: Yeah. Okay. So, this was a study that administered surveys mostly to people who identified as carnivores. So unlike Facebook groups on Reddit pages, and then ask them retrospectively, to report the extent to which they abided by a carnivore diet, and then ask them for the health benefits on all different kinds of outcomes. And quite a considerable proportion of the respondents admit to not fully following a carnivore diet like 100% carnivore diet. And so, it's, it's filled with a lot of flaws. And I think that study has really been misrepresented in some of this discourse.

CK: So, what's your what's your prescription for people listening to the show, not just the question of all meat diets, but you come away with any insights in terms of things about diets that are really important, you think?

MS: Well, I talk a bunch about this book Eat Like the Animals by these two biologists who have studied for a long time how animals eat, and their general takeaway is like, if you eat whole foods, then you can trust your your appetite. I mean, an argument that they make that I think is plausible, is that a lot of popular snack foods are designed to be savory to create a perception of having some protein in them, but they are actually very low in protein, and then correspondingly, very high in carbohydrates and a new kind of overload on these foods. And, and so their general takeaway is like processed foods is really throwing off all of the systems that the body has for gauging the nutritional content of foods. But they also in that book draw on an incredible body of work that they've done on everything from like dogs, to spiders to orangutans, to baboons.

CK: So, their study, just so I understand this. So, if they're studying dogs, or rats or spiders, they're studying what exactly?

MS: They're studying, how does an animal decide what to eat and so they start off the book with this example where they're following a baboon, I think, for a month and the baboon looks to be eating randomly, oh, it takes a little bit, it's a little at that. But when you go in there, and you, you measure the amount of I think, in particular carbohydrates and protein, you will see that on a daily basis, it's really hovering around a particular ratio. And similarly, if you provide animals with a diet very heavy one day in carbohydrates, they will seek out protein to balance that out. That is the general takeaway of all of the studies that they've conducted. And then their argument is that processed foods really throw this off.

CK: So where are you now you've written this article, you've looked into the all-meat diet? Do you basically just trust every study in every diet or are some things you think bedrock truth in the world of diets?

MS: I mean, I think this project and going into the literature on diet and going into these studies that contrast the lifestyles and diets of, of non-industrialized societies, the main thing that I've come to believe are the two main things are (a) there are so many different factors. And it's incredibly hard to isolate them. And a lot of people have very strong feelings about what the relevant factors are. And then (b) and relatedly. Like, the best solution is probably one that is one of the entire lifestyle of the entire diet, not looking for any single solution. But yeah, I would be very wary or cautious about making any kind of declarative statement.

CK: Diets seemed to be based upon what type of foods you eat, right? But maybe that's the wrong way to look at it. I mean, maybe the issue is, the quality of the food you eat, the diversity of the food you eat. Other factors in your life, like your state of happiness, the amount of exercise, how much you sleep, maybe it's all part and parcel of a bigger picture and to just look at the actual food groups you’re consuming. Maybe that's not relevant at all or irrelevant very much is all the other factors that matter more.

MS: Certainly, certainly, and I think a lot of this interest in the Paleo Diet starts with this examination of people who are not living in industrialized societies who have great health compared to the average modern American. So, like the Chobani, these Bolivian forger gardeners have, like the lowest frequency of cardiovascular disease ever recorded, lowest prostate cancer ever recorded, very little Alzheimer's. And I think it's very easy for us to think like, oh, diet is the main thing there. But there are so many, so many ways in which the life of the Chobani differ from from the life of modern Americans, I mean, even like, how much exercise they're getting, how much fiber they're getting, the extent to which they're surrounded by family. There's so many so many so many variables there. I think, just like the content of the food, and the broad food group is just very salient, and I think there's a general intuition. You are what you eat. But I remember there's like an old Jerry Seinfeld joke where he's like, at the supermarket, and he's like, I don't know what to eat. And he's like, looking at people who look healthy and he's like, what do you eat? And I think that's kind of the intuition that that we're often inspired to follow.

CK: Manvir thank you so much. It's been a real pleasure.

MS: Yeah, thanks a lot Chris. I had a lot of fun.

CK: That was Manvir Singh. He's a professor of anthropology at UC Davis. His New Yorker article is called Red Shift is an All-meat Diet What Nature Intended. Now it's time to answer your cooking questions with my co-host, Sara Moulton. Sara is, of course, the star of Sara's Weeknight Meals on public television. Also, author of Home Cooking 101.

Sara Moulton: So, Chris, what did you want to be when you grew up?

CK: I actually, believe it or not, actually, this makes perfect sense. I wanted to be a lawyer. (Yeah, right) Well, I like to argue (I noticed that about you). I liked that part of it. But then early on, you know, I started cooking. I had one of James Beards, really cookbooks. And I got interested in that. And so, I went into food pretty quickly. So, you asked me, I'll ask you. What was your fantasy career when you were seven years old?

SM: I wanted to be an ice skater ballerina like Sonia Henie. But then, you know, obviously, that went out the window. I didn't do very much about it. And then by the time I got to college, I pursued becoming a doctor, a lawyer like you, or a biological medical illustrator because I'm good at drawing and I won the biology prize in high school for my notebook. (Really?) Yeah.

CK: Can I just point out the diversity between those three things is fairly substantial. An ice skater, a medical illustrator, and a lawyer. (Yeah) you've covered a lot of ground.

SM: I know. Well, part of it was I was a feminist. I'm still a feminist, you know, and my parents wanted to make sure that my sister and I both had a career. So I went for the big ones, you know,

CK: Like ice skater.

SM: Yeah. Well, that was when I was seven. Come on

CK: All right. All right. All right. Okay, let's take a call. Welcome to Milk Street who's calling?

Caller: Roberta Holzer.

CK: How can we help you?

Caller: My daughter and her fiancé have asked me to make their wedding cake. It's a banana cake with a salted caramel filling and butter cream. So, I figured I was doing a white chocolate cream cheese butter cream. And I just can't nail the salted caramel filling. The main thing is the consistency.

CK: So, the problem is the caramel is too thick or too loose?

Caller: Too thick.

CK: When I do caramel, I just start with sugar and I put it in a skillet or saucepan no water and it’ll start melting around the perimeter with a heatproof spatula, I start moving it in towards the center. I find that really works well because if I have a light-colored stainless steel 10- or 12-inch skillet, I can see the color, which is really hard to do in a saucepan sometimes. So that's how I did that. I get it up to the right color. Off heat, add the cream slowly. And then you put it back on the heat because the cream will you know it'll the sugar will start to cease. But the question is to what temperature do you cook that caramel? What did you cook it to like 230 or 225?

Caller: the first couple of recipes that I was making it was little bit of water in the sugar. Now the last one that I made used castor sugar, you know fine sugar.

CK: it’s just a fine sugar.

SM: Yeah, it's really if you took regular sugar and put it in a food processor you end up with castor sugar.

Caller: That one the caramel came up perfect. But it's just too tight.

CK: How do you know when it's done? Do you have a candy thermometer or Instant Read thermometer?

Caller: I Eyeball it. So, when this recipe I put the sugar in the fry pan, they said a nonstick fry pan which I’ve never ever done.

CK: No, no, no, please don't do that.

SM: No.

Caller: It actually worked.

CK: Yeah, I know. But that's

SM: That’s toxic,

CK: but you don't want to get that pan of that pan gets over 500 degrees, it's not going to be good for you.

Caller: Gotcha. Okay, so do it on a medium heat. Leave the sugar undisturbed until it starts to melt into a dark caramel color. swirl around like you were saying, Turn the heat down and then add ice cold chopped up butter pieces. Then add the cream. And then they say golden syrup or corn syrup and then a pinch of salt.

CK: And then how do you know how long to cook it after you've added the cream and the salt?

Caller: Well, the temperature is on low and I'm just kind of mixing it around with a wooden spoon until everything is melted.

CK: I think that's the problem. I mean, you're obviously a great baker. But when you get to caramel sauces, you got to have a thermometer because what's happening, I will bet you is you're just either over or under cooking it so if it's too loose, it's at 225 to 230. If it's two cans He like it's over 235 to 240 What you want is 230 to 235 and, and you definitely want an Instant Read thermometer and make sure your

Caller: which I have

CK: Yeah, and just tip the skillet a little bit so you get the probe deep enough into the liquid 230 235 in that range. (Okay) Sara?

SM: I agree with Chris 100% I would take it to that dark color, take it off the heat and I would just add cream. I don't understand the butter. You need the liquid that's in the cream too. I would just go with three ingredients, and I agree with Chris about the temperature after you add the cream and it seizes up and you know, you whisk it and everything and you cook it a little more than take its temperature again

Caller: What I'm trying to get is a consistency like a spreadable.

SM: Yeah. But you got to let it cool. I think Stella Parks who's one of my favorites who did Brave Tart has a good caramel sauce recipe (she’s great) and it's the three ingredients I just told you and I've made that and I've made others with just those three ingredients and what happens when you cool it it gets spreadable you know it will be liquid to begin with. And again, if you want it to be liquid again, you know like say you want to put it on ice cream. Then you go and warm it up again. But if you want it to be spreadable, like in your banana cake, you just needed to come to room temperature and or chill it a little bit.

Caller: Gotcha,

CK: Roberta. Thank you.

SM: Yes. Okay.

Caller: Well, thank you so much for your help. Okay,

SM: Okay. Bye.

CK: This is Milk Street Radio. If you have a cooking catastrophe, please give us a ring. The number is 855-426-9843 one more time 855-426-9843 or email us at questions at Milk Street Radio.com.

SM: Welcome to Milk Street who is calling?

Caller: Hi, this is Greg. I'm calling from Texas.

SM: Hi, Greg, how can we help you today?

Caller: Well, I have a question about cheese for you. I live in a rural area, we're about 25 miles from the closest store that has you know, anything besides regular supermarket cheese. And I really like pizza and you know, getting into doing my own pizza and stuff. And when you find that chunk of cheese in the back of the refrigerator. How do you know? How do you know whether that that's on the parm is, you know, like maybe salt coming out of it or that it's mold. I know that they use mold sometimes to meet certain cheeses. So how do you know whether it's a good mold or a bad mold? And can you cut off a chunk of it and keep the rest or so it's all about moldy cheese?

SM: Well, let's talk about different kinds of mold. So, there's, you know, mold is what makes cheese cheese but in terms of kind of mold that you're talking about. There's the kind that's injected into cheese like bleu cheese with the blue veins going through it and so that should be there, that's fine. And then there's the kind of mold that's mixed into milk and put on the outside of cheeses, like the soft ripened cheeses Brie, Camembert, Saint Andre, so that all should be there. And by the way, mold can appear. I mean, real mold, the bad kind as fuzzy green, white, black, blue, or gray. So, lots to look for. The harder the cheese and the smaller the amount of liquid in there the lower moisture content hard cheese like Parmesan, it's not likely that it will get mold any time soon, you know, but in the case of cheese like that, I would cut off the mold you know, they'd say about an inch down which doesn't leave you with much cheese. And that is also true although again, it doesn't leave you with much cheese for a semi hard cheese such as a cheddar or something like that. If it's sliced or shredded, and you see any kind of mold you know the blue green brown, toss it you know when I used to work in restaurants, we had this phrase when in doubt throw it out. And that is certainly true of the sliced and shredded. Chris?

CK: I would disagree a little I think a hard cheese like parmesan or pecorino or something. It's just not going to get down into the cheese. And your slice of parmesan is probably not much more than an inch thick or inch and a half thick anyway, I wouldn't worry about it. I just take a vegetable peeler or whatever. And just peel off the outer layer because it's not going to penetrate you know and aged Parmesan that molds not going to get inside the cheese. Forget about the one-inch rule for that. I agree with Sara on the soft cheese like a mozzarella or Monterey Jack yes, just dump it because that's going to get deep into it. And it's also probably going to affect the flavor but hard cheese like Parmesan. The first of all, it gets pretty hard to get it moldy. And secondly, we just take off the surface amount and go for it. (Yeah) and also Parmesan is expensive. So, you can send me all your Parmesan with mold on it and I'll just scrape it off and use it and then we got it. We got a business deal, right? So yeah, I wouldn't worry about that stuff. By the way. Could I just ask, so you mentioned Parmesan. So, what did it look like on the outside of the parmesan it’s just cloudy or something or what?

Caller: Well, when I first saw it, it was kind of granular looking (white and granular?) right, sort of, you know, lighter colored white and granular and then, so, you know, I just kind of left it in the fridge to ponder it, you know, and then when I looked at it again, it was starting to get a little white growth and then a little piece of green growth on it. And it's like, Okay, I think I've thought about it too long.

CK: And you needed to take action quickly. Yeah, you see that sometimes on Parmesan, but I just scrape it off.

SM: I think you're doing your own science experiment there

Caller: I'm a chemist by degree so they come through sometimes

SM: Of course, okay

CK: All right. Thanks for calling.

Caller: All right. Thanks. Thank you.

SM: Bye bye. Welcome to Milk Street, who is calling?

Caller: This is Ellen.

SM: Hi, Ellen, how can we help you today,

Caller: I had some soup at a local historic restaurant. And it was a really simple chicken soup with cannoli beans and some greens in it. So, I tried to replicate it all using some chicken breasts and the usual carrots and at the end, I added beans and had opened the can and just rinsed and added them and added kale to the soup and put it in the refrigerator to use the next day or two. When I went to reheat the soup. It was horrible. It was inedible. It was so bitter, and it just tasted terrible. And I continue to see recipes using kale. But just wondering what it was that I did if there was something with a pH and in a broth using beans or what it was that made this soup. so awful, just awful.

SM: Well, there's a reason that people make kale salad with a ton of dressing. It is somewhat naturally bitter, particularly when you cut it up. Did you cook it in the soup? Was it cooked? Or did it go in raw? What happened?

Caller: I added it to the soup and then again, it cooled and then I put it in jars for another day. I've seen recipes where they use kale and sausage all the time. And I just was wondering what what was a disaster and what do I use the next time? Should I use something like just spinach, which I wanted something that a little bit of more flavor or you know chard or what you know? (yeah to the body of this soup. Right.

SM: Right

Caller: It was very good restaurant.

SM: Yeah. Chris, do you have any? Yeah. Oh, Chris is jumping up and down.

CK: Oh, hey, pick me.

SM: Okay. You over in the corner you big, tall guy?

CK: Yeah, what I would do is the same thing I would do with a soup that has pasta in it, I would add the kale or any other green to individual servings, and we cook it separately. Steam it whatever you want to do. Add it to the bowl, but you've not contaminated. The main bowl that's going to go back in the fridge overnight, because it will turn bitter. The same thing with pasta, the pasta, you know will absorb all the liquid in the soup overnight how much become mush. So never include a green directly in the big pot of soup just add it at the end separately. And that way you can do the same thing the next day.

Caller: I will remember that

CK: No, I've made the same mistake. Yeah, you spent a lot of time making a nice soup and then you have a bunch of leftover and yes, some crusty bread and a bottle of wine and whoops. Oh, yeah. Well, that's really an easy solution.

SM: Well good.

CK: All right.

Caller: I’ll remember that. Thank you.

CK: Yeah, thanks for calling. Bye bye.

SM: Yes, thanks, Ellen.

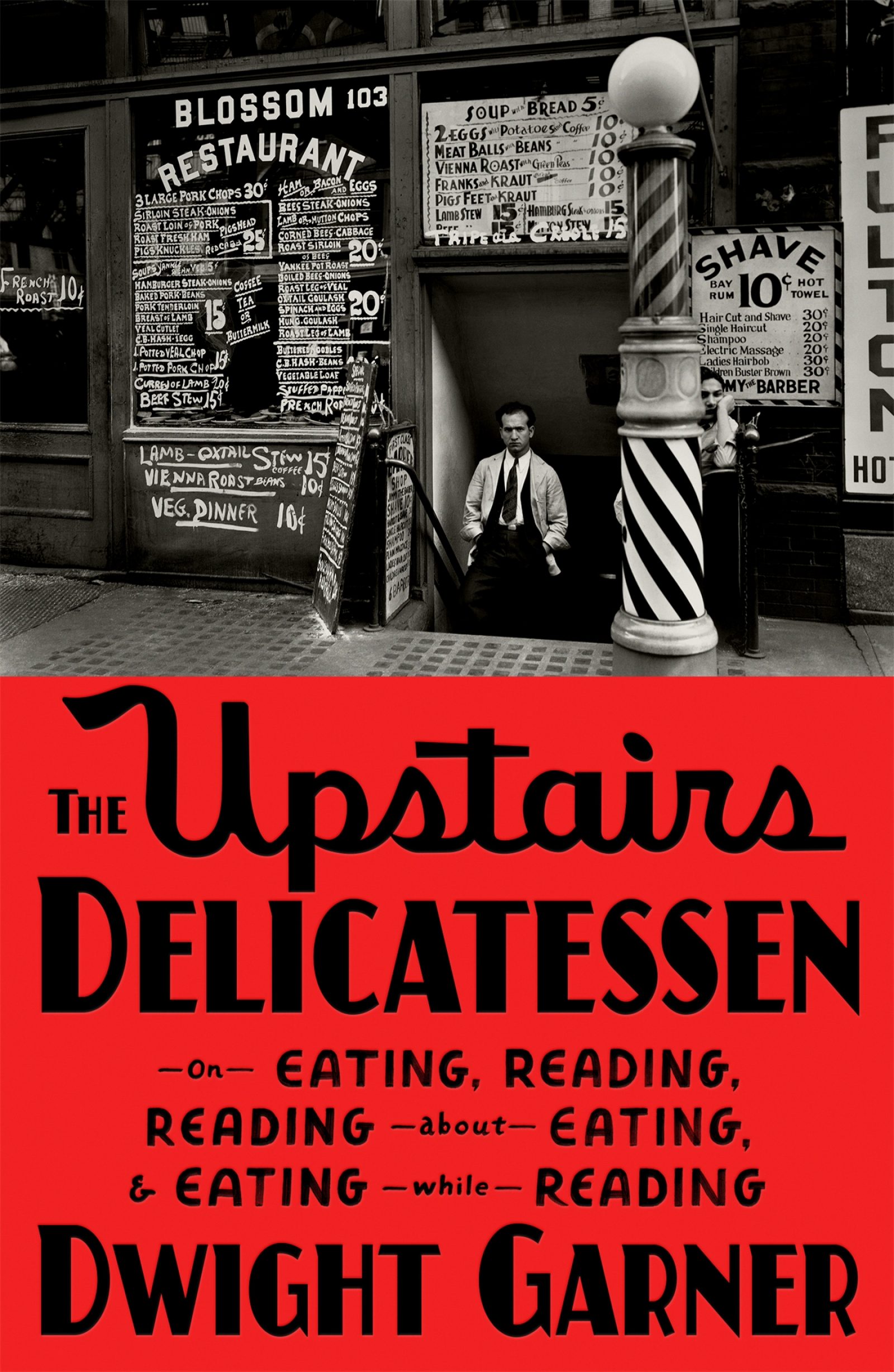

CK: This is Milk Street Radio coming up a New York Times book critic with a voracious appetite for literature and food. That's after the break. This is Milk Street Radio. I'm your host Christopher Kimball, Dwight Garner author of The Upstairs Delicatessen believes in afternoon naps, extremely dry martinis, peanut butter and pickle sandwiches and his greatest pleasure of all reading while eating, Dwight, welcome to milk straight.

Dwight Garner: Oh, it's great to be here. Thank you for having me.

CK: So, your latest book which I adore is the upstairs delicatessen. Where did the inspiration come from for that title?

DG: Yeah, you know, there's this great literary critic. He's sort of been forgotten. His name is Seymour Krim. And Seymour was was pretty well known in the 60s and 70s, maybe the 50s as well, sort of a downtown literary critic in Manhattan. And he wrote a famous essay about failure. It's called I think it's called On the Failure Business in in the process of reading this he has this great phrase, he refers to his own memory, as quote, this profuse upstairs delicatessen of mind. And I read that I thought, that is great, because you know, we all have an upstairs delicatessen where we keep our memories and our great ideas and, and it just struck me as a perfect title for a book like this one.

CK: I have about 20 pages of notes of things I want to talk to you about. So, we're not going to get through them all. But you talk about reading and eating, they're always associated for you.

DC: Yeah, you know, ever since I was a kid, I have been an enormous reader. And I've been a big eater my whole life, too. I was a pretty chubby kid. I'm a pretty chubby adult. They just go together. For me. I remember I had this ritual. When I was a kid, I would come home from school and I, I was in a new town I hadn't met didn't have any friends yet really, I would come home and drop a bunch of newspapers and books and magazines on the floor and then toddle into the kitchen and bring back a lot of food and try to make the three hours of reading in the three hours of food last, so they sort of ended at the same time.

CK: So, your book is full of great quotes about food from other authors. And one of them was from Terry Eagleton. He's a British literary critic, he writes, food is endlessly interpretable as gift; threat, poison, recompense, barter, seduction, solidarity suffocation”, I have to say, that's about as good definition as I've ever come across.

DG: Oh, I totally agree. I totally agree. And, you know, I'm interested in all the things that food means I mean, it's like literature in a way that it rewards great care, you know, you know, when you've been served writing that someone took time over and thought about in the same way that you're aware of someone serving you a really great meal doesn't have to be a complex meal. But you can sort of tell that someone put all effort and love and feeling into this. And it was sort of my life has been searching for those things, those things that are well written, well-made interesting. As you know, life is a process of discovering new flavors in new writers and new ways of looking at the world. And that's sort of what this book is about,

CK: You know, restaurant reviews over the years have gone through lots of iterations. And it started out people would just describe the meal they had whether they liked the food, and then they became highly personal. And then they then they weren't supposed to be funny. And what is a great book review, how do you you can't just describe a book or talk about whether you like it or not, you can't just tell the story of the book. What is a book review?

DG: Oh, it's such, it's such a good question. Such a hard question. I mean, a good book review sort of needs to be a work of art on its own. And by work of art, I mean, in a small way, but it needs to tell you some things about the book, of course, but I really dislike book reviews that are just plot description. And then you get to the end of the review, and its plot, plot plot, this happens, this happens. And then you know, the books good, you know, the books, okay, I just really loathe that kind of thing, because books. You know, part of why reading matters is that during the course of reading, so many things go through your mind about all kinds of ideas that the subtopics are talked about in the book, the characters, and I try to reflect, you know what it's really like to be inside a book, and I try to single out the best lines why this writing works. I try to import ideas of my own. I try to import the ways that this writers stuff may be similar to or reliant on other writers trying to bring in other cultures, bring in music. And to be a critic means to be omnivorous culturally, because it all comes together in a way. You know, I want someone to walk away feeling if they've read something that's a real piece of writing and not just a sort of soggy description of what the book is about.

CK: John Updike on food, “It never bites back. It's already dead it never tells us we are lousy lovers. Or ask us for an interview with simply begs take me cries out I'm yours”. Maybe one of the best quotes in your book.,

DG: Yeah, Updike. I mean, I think he's in my mind, probably the most gifted observer who has ever strolled planet earth and written things down. A lot of people have trouble with his work, but he's just a genius of thought and feeling. You know, every every sentence that came out of him was was somehow resonant and extra. Food was not that important to him. He said that in his memoir, although He, he used to write, he worked over a restaurant, and he said he knew, and he smelled. He smelled the aroma of lunch coming up. It was time to quit for the day. So, he would, he would work from eight until he smelled lunch cooking and I liked that.

CK: They probably started cooking lunch at 10:30 so it was a pretty nice schedule. Hunter S Thompson your wife's family’s next-door neighbor was Hunter Thompson. So, I guess he was a frequent dinner guests at the your wife's house.

DG: Yeah, we have great photographs, but they would have dinners outside in the summer and he would when he got drunk, he would just get a garden hose and spray everyone down to their their great photos of Hunter of terrorizing my wife who was all five at the time. But my wife grew up in a in a pretty elite food family and her way her father Bruce LeFevre ran restaurants in Aspen in the Napa Valley and in Idaho that were you know, the kind of places people flew in, you know, restaurant critics to, to eat at so she grew up taking frog's legs in her school lunches. You know, I had my I had my cheese and bologna sandwich.

CK: You talk Keith Waterhouse, The Theory and Practice of Lunch, which is an absolutely spectacular title. And I this is one of my favorite bits in the book, talking about lunch. “It is a conspiracy. It is a holiday. It is a euphoria made tangible serendipity given form, lunch at its lunchiest is the nearest it is possible to get to sheer bliss while remaining vertical”.

DG: Yeah, yeah. Well, Keith Waterhouse, you know, wrote the book you mentioned and it's just a thin little primer, you know that this British writer published about how to eat lunch. And it's just a charming, small, little book. But you know, he's one of those big old school lunchers, and you don't find this kind of lunch anymore. Even in literary circles in Manhattan. It's rare. You know, we're all kind of hardwired now to grab a quick sandwich or a cup of soup and get back to our desks. And I try I you know, I can't do it all the time but I try once or twice a month to have a real lunch with a friend to go somewhere decent and have a bottle of wine. And you know, once a while it stretches out a few hours. And maybe the waiters are now looking at you and hoping you’d leave soon.

CK: I love this thing. You want a cup of coffee carves out a parenthesis in the day, if you can learn to shrink the hours between the mornings last cup and the evenings first drink, you've taken a baby step towards enlightenment.

DG: Don't you agree?

CK: I mean, I think that's just everything in between sort of a grim, you know, Gulag Archipelago, until you end up with a martini at seven is that right.

DG: Especially true, right? When you have family or guests around because you love your family. You love your friends when they're in town. But, you know, once the coffee ends, you start looking at each other going, what are we going to do today? How are we going to occupy this time, and once the drinks come out in the evening, you know where you are, you're all together and having a drink so you know who you are and where you are at the coffee moments of the day. And during the drink moments? It's filling those hours in between, well, that's the hard part of living.

CK: Let's talk about martinis. You like martinis. I believe you say every night at seven you start with a martini. Is that correct?

DG: I do. And you know my wife and I have cocktail hour late we do it at seven. I think we do it late (a) because I like to work a little late. So, I feel like I deserved my cocktail more (b) I like my Martini so much that I feel like pushing it back to seven means that I it's harder to overdo it. The problem is, if the dinner is especially great or people are over if the wine becomes a second glass or third glass, then my morning at the desk might become an afternoon at the desk and I don't like that anymore. Now that I'm 58.

CK: Nathan Myhrvold treated you to one of his private dinners with many very strange courses I I had, I think a shorter version of what you went through years ago at his place. What was your takeaway from eating his food, which we should explain? Microsoft guy, wrote some amazing books on pizza and other things The Modernist Cuisine and has a laboratory where he pushes the outer limits of science in cooking.

DG: I was lucky to be invited as a journalist and he was cooking a meal in honor of his hero for Feran Adria. Am I saying that correctly? Yeah. Okay, and so he was there, Feran was there, I was there. And it was 50 courses. And, you know, and they were bigger than you might think. And more wine than you might think. And after about 27 I was a little uncomfortable after 36 I was sort of lowing like a cow, you know, but I hated it. And no knock against Nathan Myhrvold he was brilliant stuff he cooked so I don't mean to knock it I just as an experience, it was too much. And you know, part of the point that my book makes, I think is what matters more in life is who you eat with more than what you eat right? You hope that these two things combined, and you get to enjoy great food with the people you love. But given the choice of having a simple meal with people I really like to be around versus having Nathan Myhrvold’s food in front of people who didn't seem that happy to be there. Anyway, I just wasn't a great day for me and it should have been.

CK: Fast food quote. “If you spend too much time in fast food world you sense you're detaching from the literate world and this is the bit I love here, the menus or pictures as if they were crime scene photos. That's really a brilliant description.

DG: You know, I like fast food, it has its place. But there are times in life, and you feel trapped in a world. Oh, I don't know maybe you're on the highway for too long. And all you have to eat are the same fast-food places and you feel yourself detaching from literacy. I mean, you just there's their photos and not menus and, and in the food is just not good at it sort of drags your spirit down after a while. I mean, a good McDonald's hamburger or bring it on, I'll have it, you know, sometimes, but when that's all you have access to you just feel yourself dragging down. And I feel that way about books, too. I mean, I just, I mean, I have to read books for a living. But when you read bad prose for too long, that can also drag you down. I mean, you pick up a book by a good writer, and suddenly, all of your senses are alert again, the way they are with a terrifically made meal, suddenly, you're just awake. And that's what, you know, the good stuff does to you.

CK: Okay, I've got to ask you about the peanut butter and pickle sandwich. You made yourself infamous for this and took up a lot of heat. But please, are you like I'm open to try anything. So so sell me on this idea.

DG: Okay, here's the thing. I grew up watching my father eat peanut butter and pickle sandwiches. And I thought it was terrible. And then I got to be in my 30s and one day, I couldn't find anything for lunch and I made one and I was okay and made another one. And I write I think in my piece that there's something off putting just in the notion of them. It was kind of like when Lyle Lovett married Julia Roberts, you know, like, this doesn't something doesn't something's not right here. But actually, the flavor combination, I think is just a step up from peanut butter and jelly it’s just more sophisticated. It has flavor hints of things like satays and moles and other cultures do things that are almost similar. The reason I love the sandwich is that it's always there for you. And it's a great thing. Maybe the cold cuts are all gone. And there's no takeout left and no leftovers and there's nothing good in the house. I always know this peanut butter pickle sandwich and I think it's world class.

CK: Well, there are a lot of things that are always there for you that really are not delightful in life. Right I mean

DG: But don’t we all have peanut butter in the house and pickles usually. I don't know. I mean, I don't always have other things that are that delicious.

CK: You know what? I'm not going to make fun of you. I'm going to go eat one and then I'll oh please

DG: Oh, please no, no, I can take your brain. Oh, trust me. I've been sneered at by the best newspapers in the world. So, I mean, I revere your your culinary knowledge, but I'm indestructible at this point on this topic.

CK: Dwight, it's been an honor a pleasure and enormously entertaining. Thank you so much.

DG Oh, you're so kind. Thank you for having me.

CK: That was Dwight Garner writer, a book critic for the New York Times. His latest book is The Upstairs Delicatessen on Eating, Reading, Reading about Eating and Eating While Reading. You know, it's really hard not to love eccentrics, Henry Padgett, a wealthy 19th century Lord spent himself into bankruptcy by mounting amateur theatrical productions, and driving a car that emitted perfume from the exhaust pipe. John Overs faked his own death to save on provisions. His family and servants would of course fast that day out of respect and save him the cost of a few meals. But when he reappeared in the evening, one of his servants thought he was a ghost and hit him over the head with an oar killing him. William Buckland like to feast on endangered species from elephants and panthers to porpoises and crocodiles. The rumor was that he also ate the preserved heart of King Louie the 16th. And of course, now there is the modern-day Dwight Garner, who drinks martinis every night at the stroke of seven and plays a card game spider malice, where the objective is to annoy your partner. In this case, his wife. Eccentrics are not crazy. They are joyfully obsessed with creating their own special world. And as my mother often said, what's so good about reality anyway? I'm Christopher Kimball and you're listening to Milk Street Radio. After the break, we plunder the kitchen for Old Norse words with Grant Barrett and Martha Barnette, hosts of A Way with Words. That's coming up. I'm Christopher Kimball and you're listening to Milk Street Radio. Now let's head into the kitchen with JM Hirsch to talk about this week's recipe. Pakistani style chicken with biryani. JM how are you?

JM Hirsch: I'm doing great.

CK: Biryani you went to Pakistan to get a few lessons in this and a good thing because I've made it a few times, but it tends to be more porridge than the sophisticated multi layered dinner. So, what did you learn and I hope you learned not to do it my way,

JM: You know, despite my instinct in cooking, which is to just dump and go. That's the exact opposite of what you want to do with biryani and Pakistani cooks are quite adamant that the most important part of biryani is the layering. They layer the ingredients in terms of the order in which they cook them the order in which they go in the pan, and it creates layers of differences in texture and flavor in the finished dish. So, a proper biryani is not part it's actually a layer of textures, a layer of flavors, many of the same ingredients used on repeat but at different times and in different ways. c

CK: Is it just a function of translation that what we have here doesn't hew to the original concept or is this something that is more specific to Pakistan in terms of how they layer it?

JM: You know, I think part of the problem is that as American home cooks we're always looking for shortcuts and I think we tend and our recipes tend to do exactly what I do dump and go and real traditional Pakistani biryani requires careful cooking of one or two ingredients at a time. Take it out of the pot. Cook the next couple of ingredients do the onions in the ghee. Do the chicken, do the spices parboil the rice one at a time and then you reassemble them back into the pot in a specific order. Now, that's a lot of work at home, wonderful at a restaurant. Not so much at home, but I learned a special variety of biryani called matka biryani. Now, Matka is both the name of the dish it's also the name of the pot that the dish is cooked in which is kind of a rotund clay pot for lack of a better way of putting it. And in this case, most of the ingredients are prepped in advance and then just thrown together in the pot and thrown over the fire and cooked all at once not so much the fussing about precooking them and then assembling them it's kind of just putting them all in the pot. And traditionally they do it over coal fire and sealing the pot and throwing it on top of the coals and letting it go. We learned both a traditional biryani and this Matka biryani and we decided that for our version, we really wanted to kind of combine the best of both worlds. And so that's what our recipe did. And now obviously we're not using a matka t pot in ours, but we found that a Dutch oven could do an excellent job of kind of replicating the same conditions.

CK: So, in short, what are the different flavors here there's only the spices, there's ginger, etc. Garlic, you have a lot of different flavors, and they all speak out you can taste each one of them. Well

JM: Well, that's the beauty of it. So, you have onions that are caramelized really caramelized in ghee delicious, you definitely get those. Then you have a lot of whole spices, you'd have bay leaves, you'd have black peppercorns, you have clothes, green and black cardamom, cinnamon sticks, cumin seeds, you definitely feel and taste those it's a wonderful texture as well as taste. Then of course you get the punches of the fresh ginger and the fresh garlic which often are bloomed in that same ghee then you get the tender bits of chicken but then you get kind of the sweet acidity and freshness of some tomato slices, some lemon slices, you also get yogurt in there. And then of course you get the wonderful basmati rice that absorbs all of that and kind of ties it all together. Now one of the best parts and we have seen this in the cooking of both India and Pakistan, and it always fascinates me the difference it makes is the different ways they treat their spices and biryani is all about treating spices as many ways as possible. They use whole spices; they use ground spices often both have the same spice. They use them raw and they use them toasted. They use them early in the cooking and they use them late in the cooking and again all this often is the same spices on repeat, but because they use them in different forms and at different times in the cooking, you get different flavors from each one. So again, like you're getting all these different layers of complexity from the same ingredients. That's really what I loved about this dish.

CK: Sounds like a Dr. Seuss book. I liked them whole. I liked them ground I liked them raw I liked them cooked. Yes, I love my spices, Sam I am. JM thank you. A Pakistani style chicken biryani light years beyond what I'm used too, a bit of work, but I think absolutely worth it. Thank you.

JM: Thank you. You can get the recipe for Pakistani style chicken biryani at Milk Street radio.com.

CK: This is Milk Street Radio. Right now, let's check in with Grant Barrett and Martha Barnette hosts of A Way with Words. Grant and Martha what's going on this week?

Martha Barnette: Hey, Chris. This week Grant and I want to go way back in history.

Grant Barrett: Climb aboard a boat with us. And we're going to ride with the Old Norse and talk about their contributions to the English language and food of course. (Okay) so as you might expect from a seafaring people, they left some fishy words. So, fry as in small fry, meaning fish. That fry word comes from Old Norse and skate the fish not skate as in the ice sport or as in the roller sport that also comes from Old Norse. And then the scale that you would use to weigh that fish gets its name from an Old Norse word meaning bowl. And that word scale is related to skol, which is the cheer the toast that you give in Scandinavian countries when you are drinking alcohol. And that refers to the bowl or the vessel holding the alcohol.

CK: So, they weren't just out pillaging, they were actually doing some heavy lifting in the language department. That's good.

GB: Yeah, well, that's what happens when you show up and you're like, I don't want to go home. It's too far across the water. And when you stick around what do you got to do? You got to eat and so one of the things they did is they turned to the animals, and you might be imagining Great Halls with roaring fires and animals turning on spits. Well, the animals on those spits might be turned into steaks, s-t-e-a-k, and they might be on stakes s-t-a- k-e and both of those words come from the same Old Norse word, S- t- e-l-k-j- a. And in Old Norse that meant to roast on a spit. And so that word not only gave us a steak, as in the food, the meat, but also stake as on a long piece of wood with a pointed end and stick, as in, you know, a small piece of wood off of a tree,

CK: stick, steak into a steak, okay,

MB: And steak and stake are distant relatives of words like instigate, you know when you're sort of poking at somebody, and stigma which is left in your hand, you know, something sharp goes into it. But speaking of sharp things, there's also the word knife that one also comes to us from Old Norse. It blends with an old English word that was similarly pronounced the old English word was Cunniff. And the Old Norse word sounded like a ___ or something like that, because the C and the K at the beginning of those words was pronounced and was like that in a lot of English dialects until the 1600s or so.

GB: And you'll find again and again that an Old Norse word would push out an old English word. The best case that I know of is the word egg. There is a really great story that the lexicographer William Caxton tells in 1490, and it's about a ship that was anchored in a Thames Estuary, and near London, and the sailors come ashore, and they asked for eggis that's the plural of eggs in the dialect they spoke, and a woman going about her business answered him and she said, I don't speak French. And the sailors angry. He says because I don't speak French either. But he wanted eggs. And she didn't understand him saying eggis, but another sailor instead asked her for Aaron. And she says, Oh yes, so those I do have. And the problem was is that these two words, meaning EGS one Old Norse derived and one old English existed at the same time for a very long time. And it hadn't yet been settled, which would win ultimately the Old Norse word one out, but at this time in 1490, there was still kind of this push pull. And this happened again and again as the northwards kind of pushed down from the north and pushed out some old English words.

CK: So, all of this influence came because of the Vikings or Norsemen sailing to Britain to England and living there.

GB: Yeah, and it wasn't just England. It was all throughout every island that they could reach from Scandinavia, every bit of shoreline east, west, south, as far as they could go, felt their influence and you can see it linguistically throughout the Netherlands all Scandinavia, Finland, parts of Russia Iceland, of course, in Greenland, it's all there. They've at the core of these languages, even today, you'll find these kernels of influence and, and corn and kernel are two other words that come from Old Norse. And actually, corned beef. Believe it or not, but corn in corned beef refers to corns or lumps of salt being used to preserve the meat.

CK: Oh, really? Yeah, that's a good one. I liked that. Yeah.

MB: And one more Old Norse word or a word that has Old Norse roots for something that's in your kitchen is the word kettle. Now, I don't know about you all. But we watch a lot of English mysteries and comedies in our house and we kind of have a drinking game. Every time somebody says, shall I put kettle on? Or should I put the kettle on? We take a drink. But kettle is yet another word that was handed down to us through Old Norse.

GB: So Chris to end this party, I just want to hand you a bit of cake. Cake is another word that was most likely adopted into English from Old Norse pushing out another English word, just pushing it right out of the nest like a cuckoo bird. But here Chris is a piece of Old Norse cake. You can have it with your steak and your eggs. And I hope this is a good meal for you.

CK: Grant and Martha, it was a little corny, but it was very informative. Thank you.

MB: Our pleasure.

GB: Our pleasure, Chris. Take care.

CK: That was Grant Barrett and Martha Barnette hosts of A Way with Words. That's it for today. But please don't forget, you can find more than 250 episodes of our show. Wherever you get your podcasts. You can learn more about everything we have to offer it Milk Street at 177 Milk St.com. There you can become a member and get all of our recipes, access to our live stream cooking classes, and learn about our latest cookbook, Milk Street Simple. Check us out on Facebook at Christopher Kimball's Milk Street and on Instagram at 177 Milk Street. We'll be back next week with more food stories and kitchen questions and thanks as always for listening.

Christopher Kimballs Milk Street Radio is produced by Milk Street in association with GBH co-founder Melissa Baldino, executive producer Annie Sensabaugh, senior editor Melissa Allison. Producer Sarah Clapp, associate producer Caroline Davis with production help from Debby Paddock. Additional editing by Sidney Lewis audio mixing by Jay Allison and Atlantic Public Media in Woods Hole Massachusetts. Theme music by Toubab Krewe, additional music by George Brandl Egloff, Christopher Kimball’s Milk Street Radio is distributed by PRX.

In this episode

Simple, Bold Recipes

Digital Access

- EVERY MILK STREET RECIPE

- STREAMING OF TV AND RADIO SHOWS

- ACCESS TO COMPLETE VIDEO ARCHIVES

Insider Membership

- EVERYTHING INCLUDED IN PRINT & DIGITAL ACCESS, PLUS:

- FREE STANDARD SHIPPING, MILK STREET STORE,

to contiguous US addresses - ADVANCE NOTIFICATION OF SPECIAL STORE SALES

- RECEIVE ACCESS TO ALL LIVE STREAM COOKING CLASSES (EXCLUDING WORKSHOPS & INTENSIVES)

- GET YOUR QUESTIONS ANSWERED BY MILK STREET STAFF

- PLUS, MUCH MORE

Print & Digital Access

- EVERYTHING INCLUDED IN DIGITAL ACCESS, PLUS:

- PRINT MAGAZINE SUBSCRIPTION

- 6 ISSUES PER YEAR